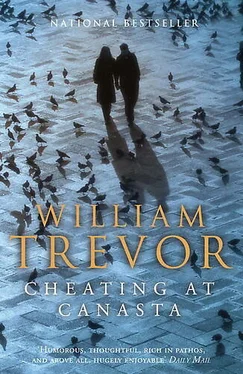

William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cheating at Canasta

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cheating at Canasta: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cheating at Canasta»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Cheating at Canasta — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cheating at Canasta», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Scuffed?’

‘Something like that.’

‘Your shoes are never scuffed.’

‘No.’

‘Well, there you are.’

He nods. ‘Yes, there you are.’

Soon after that he rises and goes upstairs again. Why did that conversation about a dream take place? It’s true that just occasionally they tell one another their dreams; just occasionally, they have always done so. But significance appears to attach to the fact that he shared his with her this morning: that is a feeling she has.

‘Why did you bother with me if I didn’t matter?’ Long after he’d decided to stay with her she asked him that. Long afterwards she questioned everything; she tore at the love that had united them in the first place; it was her right that he should listen to her. Six years went by before their daughter was born.

‘Well, I’m off.’

Like a tall, thin child he looks, his eyes deep in their sockets, his dark, conventional suit well pressed, a Paisley tie in swirls of blue that matches the striped blue shirt. His brown shoes, the pair he keeps for special occasions, gleam as they did not in his eccentric dream.

‘If I’d known I’d have come with you.’ Zoë can’t help saying that; she doesn’t intend to, the words come out. But they don’t alarm him, as once they would have. Once, a shadow of terror would have passed through his features, apprehension spreading lest she rush upstairs to put her coat on.

‘We’ll go in together next time,’ he promises.

‘Yes, that’ll be nice.’

They kiss, as they always do when they part. The hall door bangs behind him. She’ll open a tin of salmon for lunch and have it with tomatoes and a packet of crisps. A whole tin will be too much, of course, but between them they’ll probably be able for whatever’s left this evening.

In the sitting-room she turns the television on. Celeste Holm, lavishly fur-coated, is in a car, cross about something. Zoë doesn’t want to watch and turns it off again. She imagines the old flame excited as the train approaches London. An hour ago the old flame made her face up, but now she does it all over again, difficult with the movement of the train. Audrey doesn’t know that love came back into the marriage, that skin grew over the wound. She doesn’t know, because no one told her, because he cannot bring himself to say that the brief occasion was an aberration. He honours—because he’s made like that—whatever it is the affair still means to the woman whose life it has disrupted. He doesn’t know that Audrey—in receipt of all that was on offer—would have recovered from the drama in a natural way if Grace—in receipt of nothing at all—hadn’t been an influence. He doesn’t wonder what will happen now, since death has altered the pattern of loose ends.

Opening the salmon tin, Zoë travels again to the Alp Horn rendezvous. She wonders if it has changed and considers it unlikely. The long horn still stretches over a single wall. The same Tyrolean landscape decorates two others. There are the blue-and-red tablecloths. He waits with a glass of sherry, and then she’s there.

‘My dear!’

She is the first to issue their familiar greeting, catching him unaware the way things sometimes do these days.

‘My dear!’ he says in turn.

Sherry is ordered for her, too, and when it comes the rims of their glasses touch for a moment, a toast to the past.

‘Grace,’ he says. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘Yes.’

‘Is it awful?’

‘I manage.’

The waiter briskly notes their order and enquires about the wine.

‘Oh, the good old house red.’

Zoë’s fingers, gripping and slicing a tomato, are arthritic, painful sometimes though not at present. In bed at night he’s gentle when he reaches out for one hand or the other, cautious with affection, not tightening his grasp as once he did. Her fingers are ugly; she sometimes thinks she looks quite like a monkey now. She arranges the fish and the tomato on a plate and sprinkles pepper over both. Neither of them ever has salt.

‘And you, Charles?’

‘I’m all right.’

‘I worry about you sometimes.’

‘No, I’m all right.’

It was accordion music that was playing in the Alp Horn the day Zoë’s inquisitiveness drove her into it. Young office people occupied the tables. Business was quite brisk.

‘I do appreciate this,’ Audrey says. ‘When something’s over, all these years—I do appreciate it, Charles.’

He passes across the table the packet of Three Castles cigarettes, and she smiles, placing it beside her because it’s too soon yet to open it.

‘You’re fun, Charles.’

‘I think La Maybury married, you know. I think someone told me that.’

‘Grace could never stand her.’

‘No.’

Is this the end? Zoë wonders. Is this the final fling, the final call on his integrity and honour? Can his guilt slip back into whatever recesses there are, safe at last from Grace’s second-hand desire? No one told him that keeping faith could be as cruel as confessing faithlessness; only Grace might have appropriately done that, falsely playing a best friend’s role. But it wasn’t in Grace’s interest to do so.

‘Perhaps I’ll sell the house.’

‘I rather think you should.’

‘Grace did suggest it once.’

Leaving them to it, Zoë eats her salmon and tomato.

She watches the end of the old black-and-white film: years ago they saw it together, long before Grace and Audrey. They’ve seen it together since; as a boy he’d been in love with Bette Davis. Picking at the food she has prepared, Zoë is again amused by what has amused her before. But only part of her attention is absorbed. Conversations take place; she does not hear; what she sees are fingers undistorted by arthritis loosening the cellophane on the cigarette packet and twisting it into a butterfly. He orders coffee. The scent that came back on his clothes was lemony with a trace of lilac. In a letter there was a mention of the cellophane twisted into a butterfly.

‘Well, there we are,’ he says. ‘It’s been lovely to see you, Audrey.’

‘Lovely for me too.’

When he has paid the bill they sit for just a moment longer. Then, in the ladies’, she powders away the shine that heat and wine have induced, and tidies her tidy grey hair. The lemony scent refreshes, for a moment, the stale air of the cloakroom.

‘Well, there we are, my dear,’ he says again on the street. Has there ever, Zoë wonders, been snappishness between them? Is she the kind not to lose her temper, long-suffering and patient as well as being a favourite girl at school? After all, she never quarrelled with her friend.

‘Yes, there we are, Charles.’ She takes his arm. ‘All this means the world to me, you know.’

They walk to the corner, looking for a taxi. Marriage is full of quarrels, Zoë reflects.

‘Being upright never helps. You just lie there. Drink lots of water, Charles.’

The jug of water, filled before she’d slipped in beside him last night, is on his bedside table, one glass poured out. Once, though quite a while ago now, he not only insisted on getting up when he had a stomach upset but actually worked in the garden. All day she’d watched him, filling his incinerator with leaves and weeding the rockery. Several times she’d rapped on the kitchen window, but he’d taken no notice. As a result he was laid up for a fortnight.

‘I’m sorry to be a nuisance,’ he says.

She smoothes the bedclothes on her side of the bed, giving the bed up to him, making it pleasant for him in the hope that he’ll remain in it. The newspaper is there for him when he feels like it. So is Little Dorrit , which he always reads when he’s unwell.

‘Perhaps consommé later on,’ she says. ‘And a cream cracker.’ ‘You’re very good to me.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cheating at Canasta» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.