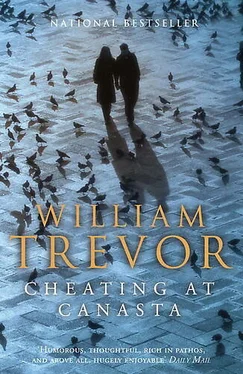

William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cheating at Canasta

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cheating at Canasta: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cheating at Canasta»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Cheating at Canasta — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cheating at Canasta», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘I never knew,’ he said in the mangel field when Teresa’s response to his proposal was to tell him that. ‘I thought you’d turn me down.’

She took the can of tea from his hand and lifted it to her lips, the first intimacy between them, before their first embrace, before they spoke of love. ‘Oh, Robert, not in a million years would I turn you down,’ she whispered.

There were difficulties, but they didn’t matter as they would have once. In an Ireland they could both remember it would have been commented upon that she, born into a religious faith that was not Robert’s, had attended a funeral service in his alien church. It would have been declared that marriage would not do; that the divorce which had brought Teresa’s to an end could not be recognized. Questions would have been asked about children who might be born to them: to which belief were they promised, in which safe haven might they know only their own kind? Such difficulties still trailed, like husks caught in old cobwebs, but there were fewer interfering strictures now in how children were brought up, and havens were less often sought. Melissa, a year older than Connie, had received her early schooling from the nuns in Clonmel and had gone on to an undenominational boarding-school in Dublin. Her brother still attended the national school at Fara Bridge. Connie went to Miss Mortimer, whose tiny academy for Protestant children—her mother’s choice because it was convenient—was conducted in an upstairs room at the rectory, ten minutes’ away along the river path. But, in the end, all three would be together at Melissa’s boarding-school, co-educational and of the present.

‘How lovely all that is!’ Teresa murmured.

There was a party at which the engagement was announced—wine in the afternoon, and Mrs O’Daly’s egg sandwiches again, and Teresa’s sponge cakes and her brandy-snaps and meringues. The sun came out after what had been a showery morning, allowing the celebration to take place in the garden. Overgrown and wild in places, the garden’s neglect went back to the time of the death, although sometimes when she’d come to keep an eye on the children Teresa had done her best with the geranium beds, which had particularly been the task of Connie’s mother.

She would do better now, Teresa promised herself, looking about among the guests as she had among the mourners, again half expecting to see the man who had left her, wanting him to be there, wanting him to know that she was loved again, that she had survived the indignity he had so casually subjected her to, that she was happy. But he wasn’t there, as naturally he wouldn’t be. All that was over, and the cousins from Mitchelstown with whom she had conversed on the afternoon of the funeral naturally weren’t there either.

Robert was happy too—because Teresa was and because, all around him at the party, there were no signs of disapproval, only smiles of approbation.

Because the wedding was not to take place until later in the summer, after Melissa’s return for the holidays, Connie and her father continued for a while to be alone together, managing, as he had said they would. Robert bought half a dozen Charollais calves, a breed he had never had on the farm before. He liked, every year, doing something new; and he liked the calves. Otherwise, his buying and selling were a pattern, his tasks a repetition. He repaired the fences, tightening the barbed wire where that was possible, renewing it when it wasn’t. He looked out for the many ailments that beset sheep. He lifted the first potatoes and noted every day the ripening of his barley.

Teresa dragged clumps of scotch grass and treacherous little nettles out of the sanguineum and the sylvaticum, taking a trowel to the docks. She cut down the Johnson’s Blue, wary of letting it spread too wildly, but wouldn’t have known to leave the Kashmir Purple a little longer, or that pratense ’s sturdy roots were a job to divide. A notebook left behind instructed her in all that.

Miss Mortimer closed her small school for the summer and Connie was at home all day then. Sometimes Melissa’s brother was there, a small thin child called Nat, a name that according to Melissa couldn’t be more suitable, since he so closely resembled an insect.

‘You want to come with us?’ Teresa invited Connie when Melissa’s term had ended and Teresa was setting off to meet her at the railway station in Clonmel. Connie hesitated, then said she didn’t.

That surprised Teresa. She had driven over specially from Fara Bridge, as she always did when Melissa came back for the holidays. It surprised her, but afterwards she realized she’d somehow sensed before she spoke that Connie was going to say no. She was puzzled, but didn’t let it show.

‘Come back here, shall we?’ she suggested, since this, too, was what always happened on Melissa’s first evening home.

‘If that’s what you’d like,’ Connie said.

The train was twenty minutes late and when Teresa returned to the farm with Melissa and Nat, Connie wasn’t in the house, and when her father came in later she wasn’t with him either, as she sometimes was. ‘Connie!’ they all called in the yard, her father going into some of the sheds. Melissa and her brother went to the end of the avenue and a little way along the road in both directions. ‘Connie!’ they called out in the garden, although they could see she wasn’t there. ‘Connie!’ they called, going from room to room in the house. Her father was worried. He didn’t say he was but Melissa and her brother could tell. So could Teresa.

‘She can’t be far,’ she said. ‘Her bicycle’s here.’

She drove Melissa to Fara Bridge to unpack her things, and Nat went with them. She telephoned the farm then. There wasn’t any answer and she guessed that Robert was still looking for his child.

The telephone was ringing again when Connie came back. She came downstairs: she’d been on the roof, she said. You went up through the trapdoor at the top of the attic stairs. You could lie down on the warm lead and read a book. Her father shook his head, saying it wasn’t safe to climb about on the roof. He made her promise not to again.

‘What’s the matter, Connie?’ he asked her when he went to say goodnight. Connie said nothing was. Propped up in front of her was the book she’d been reading on the roof, The Citadel by A. J. Cronin.

‘Surely you don’t understand that, Connie?’ her father said, and she said she wouldn’t want to read a book she didn’t understand.

Connie watched the furniture being unloaded. The men lifted it from the yellow removal van, each piece familiar to her from days spent in the bungalow at Fara Bridge. Space had been made, some of the existing furniture moved out, to be stored in one of the outhouses.

Melissa wasn’t there. She was helping her mother to rearrange in the half-empty rooms at Fara Bridge the furniture that remained, which would have to be sold when the bungalow was because there wasn’t room for it at the farm. There had been a notice up all summer announcing the sale of the bungalow, but no one had made an offer yet. ‘Every penny’ll go into the farm,’ Connie had heard Teresa saying.

Nat, whom Teresa had driven over earlier, watched with Connie in the hall. He was silent this morning, as he often was, his thin arms wrapped tightly around his body in a way that suggested he suffered from the cold, although the day was warm. Now and again he glanced at Connie, as if expecting her to say something about what was happening, but Connie didn’t.

All morning it took. Mrs O’Daly brought the men tea and later, when they finished, Connie’s father gave them a drink in the kitchen: small glasses of whiskey, except for the man who was the driver, who was given what remained in the bottle to take away with him.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cheating at Canasta» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.