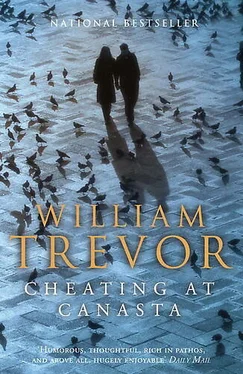

William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cheating at Canasta

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cheating at Canasta: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cheating at Canasta»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Cheating at Canasta — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cheating at Canasta», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘It hasn’t made much of a difference. Not to Chloë.

Not to either of us.’

A note of pleading kept creeping into Prosper’s voice. He couldn’t dispel it. He felt pathetic, a failure because he was unable to give a reason for what had happened. Why should they feel sorry for him? Why should they bother with a discarded man?

‘Chloë’s never been headstrong,’ her father said. He sounded strained, as if the conversation was too much for him too.

‘No,’ Prosper said. ‘No, she isn’t that.’

Her father nodded, an indication of relief: a finality had been reached.

‘You go there in the morning,’ he said, ‘you have the whole beach to yourself. Miles of it and you have it to yourself. It’s surprising what you turn up. Well, there’ll be nothing, you say. You’re always wrong.’

‘I shouldn’t have come bothering you. I’m sorry.’

‘No, no.’

‘I’ve tried to find her. I’ve phoned round.’

‘We’d best be getting back, you know.’

They said hardly anything on the walk to the house, and in the dining-room. Prosper couldn’t eat the food that was placed before him. The silences that gathered lasted longer each time they were renewed and there was only silence in the end. He should have made her tell him where she was going, he said, and saw they were embarrassed, not commenting on that. When he left he apologized. They said they were sorry too, but he knew they weren’t.

On the train he fell asleep. He woke up less than a minute later, telling himself the lunchtime beer on top of the gin and tonic had brought that about. It didn’t mean there wasn’t someone else just because she’d said it and had said it to them too, just because she never lied. Everyone lied. Lies were at everyone’s disposal, waiting to be picked up when there was a use to put them to. That there was someone else made sense of everything, some younger man telling her what to do.

The train crept into Victoria and he sat there thinking about that until a West Indian cleaner told him he should be getting off now. He pressed his way through the crowds at the station, wondering about going to one of the bars but deciding not to. He changed his mind again on the way to the Underground, not wanting to be in the flat. It took an hour to walk to the Vine in Wystan Street, where they had often gone to on Sunday afternoons.

It was quiet, as he’d known it would be. Voices didn’t carry in the Vine and weren’t raised anyway; in couples or on their own, people were reading the Sunday papers. He’d brought her here when she was still at the night school, after a Sunday-afternoon class. ‘You saved me,’ she used to say, and he remembered her saying it here. At the night school, crouched like a schoolgirl at her desk, obedient, humble, her prettiness unnourished, her cleverness concealed, she’d been dismissive of herself. Trapped by her nature, he had thought, and less so when their friendship had begun, when they had walked away from the night school together through the empty, darkened streets, their conversation at first about the two languages she was learning, and later about everything. Sometimes they stopped at the Covent Garden coffee stall, each time knowing one another better. An only child, her growing up was stifled; net curtains genteelly kept out the world. There was, for him in marriage, the torment of not being wanted any more. She was ashamed of being ashamed, and he was left with jealousy and broken pride. Their intimacy saved him too.

There was an empty table in the alcove of the wine bar, one they’d sat at. Hair newly hennaed, black silk clinging to her curves, Margo—who owned the place—waved friendlily from behind the bar. ‘Chloë’s not well,’ he said when she came to take his order, her wrist chains rattling while she cleared away glasses and wiped the table’s surface.

‘Poor Chloë,’ she murmured, and recommended the white Beaune, her whispery voice always a surprise, since her appearance suggested noisiness.

‘She’ll be all right.’ He nodded, not knowing why he pretended. ‘Just a half,’ he said. ‘Since I’m on my own.’

Someone else brought it, a girl who hadn’t been in the bar before. Half-bottles of wine had a cheerless quality, he used to say, and he saw now what he had meant, the single glass, the stubby little bottle.

‘Thanks,’ he said, and the girl smiled back at him.

He sipped the chilled wine, glancing about at the men on their own. Any one of them might be waiting for her. That wasn’t impossible, although it would have been once. A young man of about her age, a silk scarf casually tucked into a blue shirt open at the neck, dark glasses pushed up on to his forehead, was reading a paperback with the same cover as the edition Prosper possessed himself, The Diary of a Country Priest .

He tried to remember if he had ever recommended that book to her. The Secret Agent he’d recommended, and Poe and Louis Auchincloss. She had never read Conrad before. She had never heard of Scott Fitzgerald, or Faulkner or Madox Ford.

The man had blond hair, quite long, but combed. A pullover, blue too, trailed over the back of his chair. His canvas shoes were blue.

He was the kind: Prosper hardly knew why he thought so, and yet the longer the thought was there the more natural it seemed that it should be. Had they noticed one another some other Sunday? Had he stared at her the way men sometimes do? When was it that a look had been exchanged?

He observed the man again, noted his glances in the direction of the door. A finger prodded the dark glasses further back, a bookmark was slipped between the pages of The Diary of a Country Priest , then taken out again. But no one came.

It was a green-and-black photograph on the book’s cover, the young priest standing on a chair, the woman holding candles in a basket. Had the book been taken from the shelves in the flat, to lend a frisson of excitement, a certain piquancy, to deception? Again the dark glasses were pushed up, the bookmark laid on the table. People began to go, returning their newspapers to the racks by the door.

Suddenly she would be there. She would not notice that he was there too, and when she did would look away. The first time at the Covent Garden coffee stall she said that all her life she’d never talked to anyone before.

For a moment Prosper imagined that it had happened, that she came and that the man reached out for her, that his arms held her, that she held him. He told himself he mustn’t look. He told himself he shouldn’t have come here, and didn’t look again. At the bar he paid for the wine he hadn’t drunk and on the street he cried, and was ashamed, hiding his distress from people going by.

She watched while twilight went, and while the dark intensified and the lights came on in the windows of the flat that overlooked the gardens. ‘Oh, a man gets over it.’ Her mother had been sure of that. Her mother said he’d be all right, her father that they’d gone together for the lunchtime beer. She had telephoned because he would have been there; she’d guessed he would. ‘Never your type, he wasn’t,’ her mother said. Her father said stick by what she’d done. ‘Cut up he is, but you were fair and clear with him.’ Her mother said he’d had his innings.

Eventually they would say he wasn’t much. Often disagreeing, they would agree because it made things easier if that falsity seemed to be the truth. ‘Oh, long ago,’ her mother would say, ‘long ago I remarked to Dad it wasn’t right.’

A shadow smudged one of the lighted windows, then wasn’t there. The warm day had turned cold, but in the gardens the air was fresh and still. She was alone there now, and she remembered when he’d led her about among the shrubs before she came to live in the flat. ‘Hibiscus,’ he said when she asked, and said another was hypericum, another potentilla, another mahonia. She remembered the names, and imagined she always would.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cheating at Canasta» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.