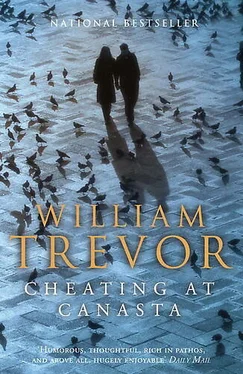

William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cheating at Canasta

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cheating at Canasta: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cheating at Canasta»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Cheating at Canasta — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cheating at Canasta», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

When she left the gardens she pulled the gate behind her and heard the lock clicking. She crossed the street and stood in front of the familiar door. All she had to do was to drop the key of the gate into the letterbox: she had come to do that, having taken it away by mistake. It would be discovered in the morning under the next day’s letters and put with them on the shelf in the hall, a found object waiting for whoever might have mislaid it.

But with the key in her hand, Chloë stood there, not wanting to give it up like this. A car door banged somewhere; faint music came from far away. She stood there for minutes that seemed longer. Then she rang the bell of the flat.

He heard her footsteps on the stairs when he opened the door. When he closed it behind her she held out the key. She smiled and did not speak.

‘It’s good of you,’ he said.

He had known it was she before she spoke on the intercom. As if telepathy came into this, he had thought, but did not quite believe it had.

‘You went down to the Coast.’

She always called it that—was never more precise—as if the town where she had lived deserved no greater distinction, sharing, perhaps, what she disliked about the house.

They had been standing and now sat down. Without asking, he poured her a drink.

‘I have a room for a few weeks,’ she said. ‘I’ll look round for somewhere.’

‘It was just there may be letters to forward. And awkward if people ring up. Awkward, not knowing what to say.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘Well, there haven’t been letters so far. And no one has rung up. I shouldn’t have gone to Winchelsea.’

‘I should have told you more.’

‘Why have you gone away, Chloë?’

Chloë heard herself answering that, in hardly more than a whisper saying she had been silly. And having said it she knew she had to say more, yet it was difficult. The words were there, and she had tried before. In the long evening hours, alone in the flat while he was at the night school, she had tried to string them together so that, becoming sentences, they became her feelings. But always they were severe, too cruel, not what she wanted, ungrateful, cold. In telling him, she did not mean to hurt, or to convey impatience or to blame. Wearied by introspection, night after night, she had gone to bed and slept; and woken sometimes when he returned, and then was glad to be there with him.

‘I didn’t know it was a silliness,’ she said.

Friendship had drawn them together. Giving and taking, they had discovered one another at a time when they were less than they became. She had always been aware of that and that it was enough, more than people often had. Still in search of somewhere to begin, she said so now. And added after a moment: ‘I want to be here.’

He didn’t speak. He wasn’t looking at her, not that he had turned away, not that he resented her muddle, or considered that she should not have allowed it to come about: she knew this wasn’t so, he had never been like that.

‘I thought it would be easy,’ she said.

There had been certainty. In her feelings she had been sure even when they were confused, even when she couldn’t think because she’d thought too much and had exhausted reason. She had clung to her certainty, had sensed its truth: that she had lost, and was losing still, a little of herself. With kindness, and delighting her, her life had been arrested, while hungrily she accepted what was on offer. But her certainty was not there as soon as she was on her own.

‘You make a mistake,’ she said, ‘and know it when you live with it.’

Prosper understood because he was quick to understand; and understanding nothing only moments ago, now understood too much. A calmness possessed him, the first time today there had been calmness, the first time since she had packed her things and gone away. He hadn’t known there’d been misgivings.

He had been jealous in the wine bar: that was what happened when emotions rampaged out of control, what panic and distress could do. It was her fault, she said. No, it was no one’s fault, he contradicted that.

She said he was forgiving. She said her mother’s contempt was not meant, and that in time her father would be pleased. Mattering so much, he thought, that didn’t matter now.

She made them scrambled eggs. They drank a little more, and the mood of relief being what it was for Chloë she celebrated their time together, recalling the Chilterns and their walks through the darkened streets in the early hours. And weekend visits to the cinema, her coming to the flat, their living there and never quarrelling, the gardens in summer.

Prosper didn’t say much and nothing at all of what he might have, not wanting to, although he knew he must. The plates they’d eaten their scrambled eggs from remained on the coffee-table. Their glasses, not yet finished with, were there; her key to the gardens was. And they were shadows in the gloom, the room lit only by a single table-lamp.

Prosper didn’t want the night to end. He loved her, she gave him back what she could: he had never not known that. Her voice, still reminiscing, was soft, and when it sounded tired he talked himself and, being with her, found the courage she had found and lost. His it was to order now what must be, to say what must be said. There had been no silliness, there wasn’t a mistake.

The Children

‘We must go now,’ Connie’s father said and Connie didn’t say anything.

The two men stood with their shovels, hesitating. Everyone else, including Mr Crozier, who had conducted the funeral service, had gone from the graveside. Cars were being started or were already being eased out of where they were parked, close to the church wall on the narrow road.

‘We have to go, Connie,’ her father said.

Connie felt in the pocket of her coat for the scarf-ring and thought for a moment she had lost it, but then she felt the narrow silver band. She knew it wasn’t silver but they had always pretended. She leaned forward to drop it on to the coffin and took the hand her father held out to her. By the churchyard gate they caught up with the last of the mourners, Mrs Archdale and the elderly brothers, Arthur and James Dobbs.

‘You’ll come to the house,’ her father invited them in case an invitation hadn’t already been passed on to them. But people knew: the cars that were slipping away were all going in the same direction, to the house three and a quarter miles away, still just within the townland of Fara.

Connie would have preferred this to be different. She would have liked the house to be quiet now and had imagined, this afternoon, her father and herself gathering up her mother’s belongings, arranging them in whatever way the belongings of the dead usually were arranged, her father explaining how they should be as they went along. She had thought of them alone after the funeral, doing all this because it was the time for it, because that was something you felt.

Her mother’s dying, and the death itself, had been orderly and anticipated. Connie had known for months that it would come, for weeks that she would throw her scarf-ring on to the coffin at the very last minute. ‘Brown Thomas’s,’ her mother had said when she was asked where it had been bought, and had given it to Connie because she didn’t want it herself any more. This afternoon, in the quiet bedroom, there would be other things: familiar brooches, familiar earrings, and clothes and shoes, of course; odds and ends in drawers. But she and her father were up to that.

‘All right, Connie?’ he asked, turning left instead of taking the Knocklofty road, which was the long way round.

There’d been no pain; that had been managed well. While she was at the hospice, and when she came home at the end because suddenly she wanted to, you could tell that there had been no pain. ‘Because we prayed for that, I suppose,’ Connie had said when everything was over, and her father said he supposed so too. More important than anything it was that there had been no pain.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cheating at Canasta» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.