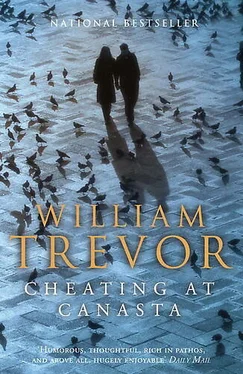

William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cheating at Canasta

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cheating at Canasta: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cheating at Canasta»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Cheating at Canasta — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cheating at Canasta», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Nothing changed, she thought when the maid had gone; and after all why should it? Persecution had become an ugly twist of circumstances, more suited to the times. Merciless and unrelenting, what was visited on the family could be borne, as before it had been. In her artificial dark it could be borne.

A Perfect Relationship

‘I’ll tidy the room,’ she said. ‘The least I can do.’

Prosper watched her doing it. She had denied that there was anyone else, repeating this several times because he had several times insisted there must be.

The cushions of the armchairs and the sofa were plumped up, empty glasses gathered. The surface of the table where the bottles stood was wiped clean of sticky smears. She had run the Hoky over the carpet.

It was early morning, just before six. ‘I love this flat,’ she used to say and, knowing her so well, Prosper could feel her wanting to say it again now that she was leaving it. But she didn’t say anything.

Once, before she came to live here, they had walked in the Chiltern hills. Hardly knowing one another, they had stayed in farmhouses, walking from one to the next for the two nights of the weekend. He had identified birds for her—stone curlews, wheatears—and wild flowers when he knew what they were himself. She was still attending the night school then and they often talked to one another in simple Italian, which was one of the two languages he taught her there. She spelled giochetto and pizzico for him; she used, correctly, the imperfect tense. He wondered if she remembered that or if she remembered her shyness of that time, and her humility, and how she never forgot to thank him for things. And how she’d said he knew so much.

‘I love you, Chloë.’

Dark-haired and slim, not tall, Chloë dismissed her looks as ordinary. But in fact her prettiness was touched with beauty. It was in the deep blue of her eyes, her perfect mouth, her profile.

‘I hate doing this,’ she said. ‘It’s horrible. I know it is.’

He shook his head, not in denial of what she said, only to indicate bewilderment. She had chosen the time she had—the middle of the night, as it had been—because it was easier then, almost a fait accompli when he returned from the night school, easier to find the courage. He guessed that, but didn’t say it because it mattered so much less than that she didn’t want to be here any more.

The muted colours of the clothes she was wearing were suitable for a bleak occasion, as if she had specially chosen them: the grey skirt she disliked, the nondescript silk scarf that hadn’t been a present from him as so many other scarves were, the plain cream blouse he’d never seen without a necklace before. She looked a little different and perhaps she thought she should because that was how she felt.

‘Where are you going, Chloë?’

Her back was to him. She tried to shrug. She picked a glass up and turned to face him when she reached the door. No one else knew, she said. He was the first to know. ‘I love you, Chloë,’ he said again. ‘Yes, I do know that.’

‘We’ve been everything to one another.’

‘Yes.’

The affection in their relationship had been the pleasure of both their lives: that had not been said before in this room, nor even very often that they were fortunate. The reticence they shared was natural to them, but they knew—each as certainly as the other—what was not put into words. Prosper might have contributed now some part of this, but sensing that it would seem like protesting too much he did not.

‘Don’t,’ he begged instead, and she gazed emptily at him before she went away.

He heard her in the bedroom when she finished with the Hoky in the hall. The telephone rang and she answered it at once; a taxi-driver, he guessed, for Clement Gardens was sometimes difficult to find.

Exhausted, Prosper sat down. Middle-aged, greying a little, his thin face anxious, as it often was, he wondered if he looked as disturbed and haggard as he felt. ‘Don’t,’ he whispered. ‘For God’s sake, don’t, Chloë.’

No sound came from the bedroom, either of suitcases and bags being zipped or of footsteps. Then the doorbell rang and there were voices in the hall, hers light and easy, polite as always, the taxi-man’s a mumble. The door of the flat banged.

He sat where she had left him, thinking he had never known her, for what else made sense? He imagined her in the taxi that was taking her somewhere she hadn’t told him about, even telling the taxi-driver more—why she was going there, what the trouble was. There had been no goodbye. She hadn’t wept. ‘I’m sorry,’ was what she’d said when he came in from the night school more or less at the usual time. His hours were eight until half past one and he almost always stayed longer with someone who had fallen behind. He had this morning, and then had walked because he felt the need for fresh air, stopping as he often did for a cup of tea at the stall in Covent Garden. It was twenty to three when he came in and she hadn’t gone to bed. It had taken her most of the night to pack.

Prosper didn’t go to bed himself, nor did he for all that day. There hadn’t been a quarrel. They had never quarrelled, not once, not ever. She would always cherish that, she’d said.

He took paracetamol for a headache. He walked about the flat, expecting to find she had forgotten something because she usually did when she packed. But all trace of her was gone from the kitchen and the bathroom, from the bedroom they had shared for two and a half years. In the afternoon, at half past four, a private pupil came, a middle-aged Slovakian woman, whose English he was improving. He didn’t charge her. It wasn’t worth it since she could afford no more than a pittance.

All day Chloë’s work had been a diversion. Now there was a television screen, high up in a corner, angled so that it could be seen without much effort from the bed. People she knew would have put her up for a while, but she hadn’t wanted that. Breakfast was included in the daily rate at the Kylemore Hotel; and it was better, being on her own.

But the room she’d been shown when she came to make enquiries a week ago wasn’t this one. The faded wallpaper was stained, the bedside table marked with cigarette burns. The room she’d been shown was clean at least and she’d hesitated when this morning she’d been led into a different one. But, feeling low, she hadn’t been up to making a fuss.

From the window she watched the traffic, sluggish in congestion—taxis jammed, bus-drivers patient, their windows pulled open in the evening heat, cyclists skilfully manoeuvring. Still gazing down into the street, Chloë knew why she was here and reminded herself of that. But knowing, really, was no good. She had been happy.

It was the second time that Prosper had been left. The first time there had been a marriage, but the separation that followed the less formal relationship was no less painful; and in the days that now crawled by, anguish became an agony. He dreaded each return to the empty flat, especially in the small hours of the morning. He dreaded the night school, the chatter of voices between classes, the brooding presence of Hesse, who was its newly appointed principal, the hot-drinks machine that gave you what it had, not what you wanted, the classroom faces staring back at him. ‘All right?’ Hesse enquired, each guttural syllable articulated slowly and with care, his great blubber face simulating concern. In Prosper’s dreams the contentment he had known for two and a half years held on and he reached out often to touch the companion who was not there. In the dark the truth came then, merciless, undeniable.

When that week ended he went to Winchelsea on the Sunday, a long slow journey by train and bus, made slower by weekend work on different stretches of the railway line.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cheating at Canasta» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.