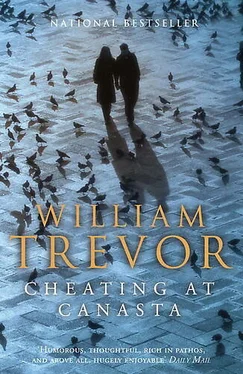

William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cheating at Canasta

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cheating at Canasta: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cheating at Canasta»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Cheating at Canasta — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cheating at Canasta», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘It’s hard,’ Eoghan said. ‘I know all this is hard, Mamma.’ He reached out for her hand, which Tom would have been shy of doing, which Angela might have in a daughterly way.

‘It’s only hard to imagine,’ she said. ‘So big a thing.’

They could keep going in a sort of way, Eoghan said. Tom and his family would come to live at Olivehill, the house they were in now offered to whoever replaced Kealy when the time for that arrived. A woman could come in a few mornings a week when Kitty Broderick went, economies made to offset any extra expense.

‘But Tom’s right,’ Eoghan said, ‘when he’s for being more ambitious. And bolder while we’re at it.’

She nodded, and said she understood, which she did not. The friendship of her sons, their respect for one another, their confidence in their joint ventures had always been a pleasure for her. It was something, she supposed, that all that was still there.

‘And Angela?’ she asked.

‘Angela’s aware of how things are.’

That night Mollie dreamed that James was in the drawing-room. ‘No, no, no,’ he said, and laughed because it was ridiculous. And they went to the Long Field and were going by the springs where men from the county council had sheets of drawings spread out and were taking measurements. ‘Our boys are pulling your leg,’ James told them, but the men didn’t seem to hear and said to one another that Mountmoy wouldn’t know itself with an amenity golf-course.

Afterwards, lying awake, Mollie remembered James telling her that the Olivehill land had been fought for, that during the penal years the family had had to resort to chicanery in order to keep what was rightfully theirs. His father had grown sugar beet and tomatoes at the personal request of de Valera during the nineteen forties’ war. And when she dreamed again James was saying that in an age of such strict regulations no permission would be granted for turning good arable land into a golf-course. History was locked into Olivehill, he said, and history in Ireland was preciously protected. He was angry that his sons had allowed the family to be held up to ridicule, and said he knew for a fact that those county-council clerks had changed their minds and were sniggering now at the preposterousness of a naïve request.

‘We mustn’t quarrel,’ Eoghan said.

‘No, we mustn’t quarrel.’

She had been going to tell him her dream but she didn’t. Nor did she tell Tom when he came at teatime. He was the sharper of the two in argument and always had been; but he listened, and even put her side of things for her when she became muddled and was at a loss. His eagerness for what he’d been carried away by in his imagination was unaffected while he helped her to order her objections, and she remembered him—fair-haired and delicate, with that same enthusiasm—when he was eight.

‘But surely, Tom,’ she began again.

‘It’s unusual in a town the size of Mountmoy that there isn’t a golf-course.’

She didn’t mention permission because during the day she had realized that that side of things would already have been explored; and this present conversation would be different if an insurmountable stumbling-block had been encountered.

‘In the penal years, Tom—’

‘That past is a long way off, Mamma.’

‘It’s there, though.’

‘So is the future there. And that is ours.’

She knew it was no good. They had wanted their father’s blessing, which they would not have received, but still they had wanted to try for it and perhaps she’d been wrong to beg them not to. His anger might have stirred their shame and might have won what, alone, she could not. That day, for the first time, her protection of him felt like betrayal.

At the weekend Angela came down from Dublin, and wept a little when they walked in the woods. But Angela wasn’t on her side.

The front avenue at Olivehill was a mile long. Its iron entrance gates, neglected for generations, had in the end been sold to a builder who was after something decorative for an estate he had completed, miles away, outside Limerick. The gates’ two stone pillars were still in place at Olivehill, and the gate-lodge beside them was, though fallen into disrepair. Rebuilt, it would become the clubhouse; and gorse was to be cleared to make space for a car park. A man who had designed golf-courses in Spain and South Africa came from Sussex and stayed a week at Olivehill. A planning application for the change of use of the gate-lodge had been submitted; the widening of access to and from the car park was required. No other stipulations were laid down.

Mollie listened to the golf-course man telling her about the arrangements he had made for his children’s education and about his wife’s culinary successes, learning too that his own interest was water-wheels. She was told that the conversion of Olivehill into a golf-course was an imaginative stroke of genius.

‘You understand what’s happening, Kitty?’ Mollie questioned her one-time parlourmaid, whose duties were of a general nature now.

‘Oh, I have, ma’am. I heard it off Kealy a while back.’

‘What’s Kealy think of it then?’

‘Kealy won’t stay, ma’am.’

‘He says that, does he?’

‘When the earth-diggers come in he won’t remain a day. I have it from himself.’

‘You won’t desert me yourself, Kitty?’

‘I won’t, ma’am.’

‘They’re not going to pull the house down.’

‘I wondered would they.’

‘No, no. Not at all.’

‘Isn’t it the way things are though? Wouldn’t you have to move with the times?’

‘Maybe. Anyway, there’s nothing I can do, Kitty.’

‘Sure, without the master to lay down the word, ma’am, what chance would there be for what anyone would do? You’d miss the master, ma’am.’

‘Yes, you would.’

When February came Mollie took to walking more than she’d ever walked in the fields and in the woods. By March she thought a hiatus had set in because there was a quietness and nothing was happening. But then, before the middle of that month, the herd was sold, only a few cows kept back. The pigs went. The sheep were kept, with the hens and turkeys. There was no spring sowing. One morning Kealy didn’t come.

Tom and Eoghan worked the diggers themselves. Mollie didn’t see that because she didn’t want to, but she knew where a start had been made. She knew it from what Eoghan had let drop and realized, too late, that she shouldn’t have listened.

That day Mollie didn’t go out of the house, not even as far as the garden or the yards. Had she been less deaf, she would have heard, from the far distance, rocks and stones clattering into the buckets of the diggers. She would have heard the oak coming down in the field they called the Oak Tree Field, the chain-saws in Ana Woods. A third digger had been hired, Eoghan told her, with a man taken on to operate it, since Kealy had let them down. She didn’t listen.

It was noticed then that she often didn’t listen these days and noticed that she didn’t go out. She hid her joylessness, not wishing to impose it on her family. Why should she, after all, since she was herself to blame for what was happening? James would have had papers drawn up, he would have acted fast in the little time he’d had left, clear and determined in his wishes. And nobody went against last wishes.

‘Come and I’ll show you,’ Eoghan offered. ‘I’ll take you down in the car.’

‘Oh now, you’re busy. I wouldn’t dream of it.’

‘The fresh air’d do you good, Mamma.’

She liked that form of address and was glad it hadn’t been dropped, that ‘master’ and ‘mistress’ had lasted too. The indoor servants had always been given their full names at Olivehill, and Kitty Broderick still was; yard men and gardeners were known by their surnames only. Such were the details of a way of life, James had maintained—like wanting to be at one, which he himself had added to that list.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cheating at Canasta» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.