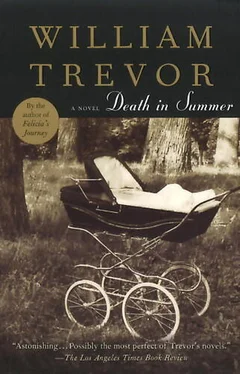

William Trevor - Death in Summer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Death in Summer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death in Summer

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death in Summer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death in Summer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death in Summer — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death in Summer», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Bloody hell!’ he loudly and with suddenness exclaims. ‘Jesus bloody hell!’

In astonishment, Zenobia looks across the table at him. He is not given to this. Coarseness and blasphemy have never been his way.

‘We should have drawn special attention to that girl and her ring,’ his explanation comes, his tone still cross. ‘Out of the way, that episode was.’

‘Oh, surely not.’

‘Out of the way from start to finish.’

‘Well, mention it when they come back. No call for rowdiness.’

‘I said at the time. High and low she took him, after a ring that never saw the light of day in this house. I said it to you where you’re sitting now.’

‘No call for violent language neither.’

‘A time like this, it’s normal to speak straight out.’

His continuing vexation infects Zenobia. She responds as, years ago, she occasionally did in their circumspect marriage.

‘Was it speaking straight out to mention your bones to that man? Ridiculous, that sounded.’

‘What bones? What’re you talking about?’

‘It’s meaningless when you say you’ll lay down your bones. If you should have spoken about the girl and her ring, why didn’t you instead of going on about your bones?’

Astonished in turn, Maidment goes quiet. He stares at the scrubbed surface of the table, the furrows in the grain. Nothing more is said.

At half past five, faint beads of dew on the morning cobwebs, Thaddeus crosses one lawn and then the other, Rosie trailing behind him. He gathers tools from the shed in the yard: pliers and a hammer with a claw, wire-cutters and spade. The day he made the pen for Letitia’s pullets — out of sight, behind the summer-house — it took all morning. Dismantling promises to be quicker.

It was Letitia who planted the geranium banks he passes now — clumps of Lohfelden and Ridsko and Mrs. Kendall Clark, Lily Lovell and Lissadell. She wanted to have a part of the garden hers and cleared spring weeds and cut down nettles and dug up docks. She made her own wild corner, and her calm presence seems fleetingly there again among the echium and poppies, a Bach cantata soft on her transistor. Surely it is enough that she has died. Thinking that, for a moment it all seems one to Thaddeus, too: the death and what so soon has followed it.

The thought still there, he patiently extracts the staples that attach the chicken-wire to the posts he drove into the grass, dropping the staples into one half of a plastic container that once held spring water. He rolls up each length of wire as it becomes free and levers the posts back and forth until they’re loose enough to pull up. Only one does not come easily and he has to use the spade.

There are four coils of chicken-wire when he has finished, and eight posts which can be used for something else. The door he made of chicken-wire on a frame may be useful also. He fills the holes left in the grass with soil, ramming it home with his heel.

White sweet-pea thrives not far from where he works. Herbs are separated by narrow brick-paved paths: tarragon and apple-mint and basil, sage and parsley and rosemary and thyme, chives in profusion. A twisted trunk of wistaria is as thick as a man’s thigh, its tendrils stretching for yards on either side of the archway in which, yesterday, the door was found open. It is another cloudless day.

The branches of the cherry tree that marks this corner stretch over the patch that was suitable for hens. Tidying up there, after two hours’ work, Thaddeus hears the distant crunch of car tyres and pauses in his search for the short lengths of binding wire he has used, lost somewhere in the grass. Voices carry to him. A police car has returned.

13

The detective inspector of yesterday, whose name has registered neither in the kitchen nor the drawing-room although it was repeated in both, is less dishevelled this morning. He is wearing a different tie and a clean shirt, the trousers of his brown suit pressed overnight. His name is Baker, christened Brian Keith, but known as Dusty among his friends and colleagues.

The hall door is open when he reaches it, leaving Denise Flynn on the car phone. The hall itself is empty, but the beaky-faced houseman appears, his unobtrusive tread suggesting to a detective’s trained observation a man who enjoys moving silently. Yesterday he had him down as slippery. There was a Maidment he arrested once, an unsuccessful embezzler.

‘You’ve been informed we have a description, Mr. Maidment?’ Since the opportunity is there, he feels he may as well start with this man as with anyone. He repeats the description that has come in, from a railway employee and kids playing on the towpath: a girl with a bundle, in a hurry on the towpath, nervous on the railway platform, a girl of slight build, with glasses, in a T-shirt with a musical motif on it, short blue denim skirt.

‘Ring a bell at all, Mr. Maidment?’

Hoping to hear in response, after the usual moment of blankness, that this could possibly fit a girl of the locality, the detective hears instead that this is a girl who recently came twice to the house, the first time after a nursemaid’s job that was advertised, the second in search of a ring she’d dropped.

‘When was this, Mr. Maidment?’

‘The ring was less than a week ago.’

This is confirmed when the question is put later to the father and the grandmother, who also agree that the description fits.

‘You’ll have the details, sir? Name, address? She would have passed all that on?’.

‘Ernily something, I think.’

Mrs. Iveson shakes her head. Emily was the one with frizzy black hair.

Other first names are mentioned, Kylie and Dawne, but it’s agreed that the girl in question was neither. No addresses or telephone numbers were retained, nor even known, none of the girls being suitable for the position.

‘The girl we’re talking about, would she have brought references? Would there be a name that comes back from being on a reference, sir?’

They remember a reference, passed from one to the other, then back to the girl. It hadn’t impressed them.

‘And the name on it, sir? Madam? Nothing at all comes back? Nothing jotted down, sir?’

‘It wasn’t necessary.’

‘The girl returned, I understand. A ring she lost while she was here?’

‘Yes.’ There is a pause. ‘We mentioned the girl yesterday.’

The man in the hall said the same, regretting he had not made more of this girl’s return to the house.

‘She just turned up, did she?’

‘She telephoned beforehand to ask if we’d found her ring.’

‘I understand, sir. And would she have given her name then?’

‘She may have. But I think I’d remember if she had.’

It has been a shock that the abductor is known; that shows in both their faces, his drawn and exhausted, hers nervily agitated. He remains still, motionless by the bookcases; she moves about, quite different from yesterday. He apparently was puzzled at first, when the girl was on the phone, not knowing who she was, then realizing she was one of the girls they’d interviewed.

‘You realized which girl particularly, sir?’

‘The last one who came, she said, and I remembered.’

‘I understand there have been phone calls to the house during the past few weeks. Nuisance calls.’

‘Yes.’

‘And you answered the phone yourself, sir, when the girl rang about her ring?’

‘Yes, I did.’

‘You don’t recall exactly what was said, I suppose?’

‘She asked if the ring had been found.’

‘And of course it hadn’t?’

‘No.’

‘She then suggested coming out here again?’

‘While she was still on the phone I looked where she’d been sitting. There was nothing there.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death in Summer»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death in Summer» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death in Summer» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.