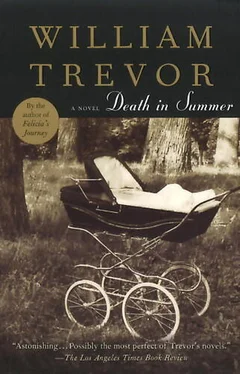

William Trevor - Death in Summer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Death in Summer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death in Summer

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death in Summer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death in Summer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death in Summer — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death in Summer», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It’s quiet in the lane once the tractor noise has faded, no aeroplanes to look up at, no one about. The edges of the leaves are withering; there are a few white flowers, a few pink and yellow, in among the brambles. The sky is grey and dull, all sunshine gone, but Albert doesn’t mind: there are the flowers, even though they’re past their best. ‘Immortal, Invisible’ is the hymn that is in his mind. He has never walked in the country before.

There’s a wood behind a fence of barbed wire. Some sort of path through fields he was told about, but he doesn’t look for it. A breeze is getting up, rippling through a crop and in the high grass of a meadow. Merle said she came from the country, a big house by a river, brown horses grazing, like in the picture above Mr. Hoates’s desk. Don’t ever throw down sweet papers in a country field, Miss Rapp ruled. Because the country was our heritage.

Drops of rain begin, heavy drops that spread damp patches on Albert’s jacket and are cold on his forehead and his cheeks. Cows move slowly in a field, all going together, maybe for shelter. The gateless pillars that have been described are straight ahead. The drops have become a downfall, puddles already filling, the surface of the lane awash.

On the drive, the parched laurels drip and glisten; water streams into gratings; Albert’s shoes are soaked. He blinks the rain out of his eyes, he turns up the collar of his jacket. It is the first time rain has fallen on his uniform. Who’d ever have thought that it could rain?

‘A look of an egg about the face,’ Maidment reports. ‘With eyes that do not express a lot, if anything at all. Drenched from head to foot. I wonder he didn’t shelter.’ He leaves the best till last. ‘Togged out by the Salvation Army.’

‘Why’s that?’

‘I’m telling you what’s there.’

‘You know when the Salvation Army was mentioned.’

This has struck Maidment too. A Salvation Army barracks, or whatever the term is. The name of the street was given, but he has forgotten.

‘He say what he wanted?’

‘A word. He said he wanted a word. He called me sir.’

‘It’ll be that boy’

Weeks have passed since their outing to Scarrow Hill. On subsequent Sundays there have been visits to Notham Manor and the Dolls’ Museum at Hindesleigh, to Tattermarle Castle and a steam-engine display in a field. On each occasion Zenobia has attended church en route while Maidment read the News of the World in the Subaru. ‘No, I want to forget about it,’ Zenobia has firmly laid down when attempts have been made by her husband to embark on fresh speculation about the abduction. She doesn’t at all like the advent of this boy.

‘Come for another handout.’ And Maidment pronounces fiscal gain to be the universal language of the age, cure for all ills, salver of all conscience.

‘You’ll need to take in tea,’ Zenobia interrupts this flow, lifting a cherry cake from a tin. ‘You have tobacco on your breath,’ she points out also. ‘Take Listerine, I would.’

‘You ever get the planes going over?’ Albert asks. ‘Alitalia? Icelandic? Air Canada with the leaf? Air India, you get?’

Nothing much in the way of plane traffic, they say, the man saying it first. ‘Mrs. Iveson,’ she said when he came into the room and he wondered how she was spelling that, but didn’t ask. ‘Mr. Davenant,’ she said, and he didn’t say he knew.

Virgin has the pin-up, he says, the Saudis have the swords, the Irish the shamrock. ‘You’d know a shamrock never grew in England, sir?’

The man Pettie took the shine to nods. The woman she didn’t like says the shamrock is special to St. Patrick, which he had ready to say himself. Pettie got off on the wrong foot with her on account she gave short on the fares, but it could have been she didn’t mean to. It could have been she hadn’t checked it out. He didn’t say it to Pettie, a waste of breath that would have been. Pettie didn’t go for her and that was that.

‘He took it as a sign.’ He explains in case there is confusion about the shamrock. ‘A three-leaved clover.’

‘Yes, he did.’

‘You’d know it’s a bird on a lot of them, sir? One way or another, not that people realize. Singapore for starters, sir. Then again Indonesia. Then again Nigeria and the Germans.’

‘I see.’

‘Not much to Cathay Pacific, sir. Not much to Egypt Air.’

‘No, I suppose not.’

‘They give me the money, sir. What you sent.’

They nod their heads. A Friday it was when she came out here the first time, a Saturday a.m. when she said Thaddeus Davenant the first time in the Soft Rock.

‘We’re extremely grateful to you,’ the woman says.

‘They said you was grateful.’

‘More than we can express.’

The man who opened the door comes in with a tray. It’s laden down with a cake and toast cut into strips, and a plate of biscuits, and jam, and plates and cups and saucers. You can tell there’s butter on the toast from the glisten.

‘Georgina Belle recovered from her adventure?’ He planned to say that first of all, but he forgot, so he says it now. Then he asks about Iveson, how it’s spelt, explaining that he takes an interest in a name.

‘I, v, e,’ the woman says, ‘s, o, n.’

The man puts the tray down. He fiddles with the cups and saucers, setting them out. Pettie didn’t go for him, either. She didn’t like the way he looked at her when he opened the front door. You wouldn’t trust a man like that, she said. vIveson,’ the woman repeats, and he’s put in mind of Ivy On Her Own, who sang for Leeroy. Still not speaking, the man who brought the tray in goes away.

‘Why d’you call her that?’ the woman asks. ‘Georgina Belle?’

‘The baby that is, Mrs. Iveson.’

Just Georgina it is.’

He mentions Leeroy. Ivy On Her Own, he explains, Bob Iron and the Metalmen. ‘I thought it was Georgina Belle,’ he says, and explains that Leeroy’s singers didn’t exist, that no one could hear them except Leeroy. Probably no one can to this day, he explains.

‘I see,’ the woman says.

‘One of those things, like.’

He likes the cup his tea’s in, flowers all over it and a gold ring on the edge, and another round the saucer. He likes the cake he’s eating, as good as anything Mr. Kipling does. ‘You know Mr. Kipling at all?’ he asks them and then he realizes they think he means personally so he explains that Mr. Kipling is a cake-maker. Mrs. Biddle is partial to Mr. Kipling’s almond slices, he says, anything with jam in it and Mrs. Biddle’s away. When she was younger she had to watch her waist.

‘All right then, Mrs. Iveson?’

‘Yes, of course.’ vNot that Mrs. Biddle’s stout these days. Skin and bone, as a matter of fact.’

‘Would you like to see Georgina? I’m sure you would.’

She goes away and Thaddeus Davenant offers him the biscuits. The dog’s asleep, stretched out in a corner. There are more books in those bookcases than he has ever seen in a living-room before. Albert says that, keeping things going.

‘What’s his name, sir?’ he inquires, looking over at the dog.

‘Rosie.’

He remembers. And he remembers this same dog described, friendly and brown, and how he warned her that you can’t be too careful with a dog. The rain’s still coming down, sounding on the window glass.

‘They don’t like a uniform, sir. Depending on the dog, a postman said to me once.’

‘Postmen have a lot to put up with in that respect.’

He’s a man who doesn’t say much, which maybe was what she took to. She could sit in silence with a person, it didn’t matter. When they lived in the glasshouse she didn’t speak herself for hours on end. It would come on dark and he daren’t flash on his torch, but she never minded. She’d things to think about, she said.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death in Summer»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death in Summer» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death in Summer» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.