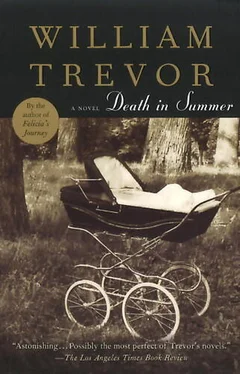

William Trevor - Death in Summer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Death in Summer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death in Summer

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death in Summer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death in Summer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death in Summer — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death in Summer», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘You read all them books, sir?’

‘Not all of them. But most, I think, one way or another.’

Mrs. Biddle has a few behind glass in the hall. Not his business, so he never took one out. Magazines are more Mrs. Biddle’s thing. Hello! and Chic he gets her, the People’s Friend.

‘Read a Book with Me, by the Man Who Sees. You come across that, sir? I come across it somewhere, maybe Miss Rapp it was. The Home Encyclopaedia we had. Arthur Mee’s Talhs for Boys, sir? You’d have known that in your young days?’

‘No. No, I’m afraid I didn’t.’

‘You ever go on Varig, Mr. Davenant? Varig Brazilian?’ vActually, I’ve never flown.’ vThey have the rainforest down Brazil way.’

‘Yes, they do.’

Mrs. Iveson is back with the baby, and the baby’s eyes are fixed on him, not that she shows recognition. Too much to expect, in a baby.

‘Hullo, there,’ he says.

She puts the baby down on a chair, bunching it back into a corner, with a cushion in front of it in case it tumbles off, although it’s hard to see how it could.

‘Is it Albert?’ she asks. ‘I think at the time they said Albert.’

‘What?’

‘Did you tell us your name?’

He feels foolish, as he did when he forgot about the dog being mentioned. He should have given his name when he entered the room. Best to call it an adventure was what he was concentrating on, best to smile, which he did, only he forgot to give his name.

‘Albert Luffe.’

‘We guessed when we saw your uniform. We were told you took Georgina to one of your hostels.’

‘You think it’s all right?’ He strokes one lapel and then the other, to indicate what he means. They say it suits him. ‘You look ridiculous, dear,’ Mrs. Biddle said the first time he wore it, taking against it because it was something new. ‘You’re in that uniform again,’ she has taken to calling out, knowing he has it on when he doesn’t look in to say goodbye to her on his way out. Mrs. Biddle needn’t see it if she doesn’t want to, no way he’d foist something new on her. He didn’t tell her Captain Evans is going to teach him an instrument, soon as they find out which one he’d be all right on. Best not to bring it up if it isn’t what she wants.

‘Sorry about that, Mrs. Iveson.’

‘Sorry?’

‘I had it in mind to give my name first thing. Otherwise you’d be confused.’

‘It doesn’t matter in the least.’

‘I wasn’t wearing my uniform that day, as a matter of fact. I wasn’t in the Army even. To tell you the truth, I wouldn’t be in the Army if it wasn’t for that day.’

She smiles at him. She says they owe the baby’s life to his quick thinking, knowing what to do.

‘No sweat, Mrs. Iveson.’

The rain has soaked through a place in his jacket and through his trousers at the knees. He feels the dampness, colder now than a moment ago. When he gets back he’ll iron the uniform first thing in case there’s damage done. It was definitely Miss Rapp who was on about the Man Who Sees, some different magazine because Hello! and Chic weren’t going then.

‘She wasn’t kicking up a row, nothing like that. Only gurgling a bit. Many’s the time we had a baby left there. In the coke shed. By the doors. Many’s the time we’d hear the screeching first thing, wake you up it would. Newborn, maybe a day, maybe a week. “What’ll we call it?” Mrs. Hoates would say.’

The other man comes back with water for the tea. He lifts the teapot lid and pours some in. He checks the food, making sure there’s enough. He still doesn’t speak. They take no notice of him.

Mrs. Hoates would say what’ll we call it, but every time she’d pick the name herself. You’d make a suggestion and she’d say lovely, but then she’d go for something else. He explains that to them, thinking he’d better, in case of misleading. vWhat’s this?’ She smiles at him. ‘What’s this about, Albert?’

‘The Morning Star, Mrs. Iveson.’

‘I think it’s where he found Georgina,’ Thaddeus Davenant says. ‘A derelict children’s home, they said.’

Albert stirs two lumps of sugar into a fresh cup of tea. The biscuits are mixed creams and chocolate-coated. He takes one that has raspberry jam in with the cream. Another thing is, it was Miss Rapp who gave the information about the shamrock, how the slave boy banished the toads and serpents, bringing in the harmless weed instead.

‘Spaxton Street,’ he says. ‘Round the Tipp Street corner is where the brown yard doors are. You know the neighbourhood, sir? Fulcrum Street?’

‘I’m afraid I don’t.’

‘You were a child in the home yourself, Albert?’

He says he was. He gives some other names because they’re interested. He tells the story of Joey Ells, the Sunday when it snowed. Crippled, he says, and she asks about the tank, and he explains that Joey Ells thought there were steps where there weren’t. An iron ladder there used to be, only it gave way under rust.

‘What a terrible thing!’

You can see they both think it was terrible, and he tells how Miss Rapp walked away from the Morning Star the next day. He mentions Joe Minching and Mrs. Cavey. Mrs. Cavey did the cooking, he explains. The milkman sometimes stopped to play football in the yard, clattering down his crate of bottles as a goalpost.

‘Your home?’ she wants to know. ‘You still think of it as home, Albert?’

‘I have a room with Mrs. Biddle these days. Appian Terrace. You know Appian Terrace, sir?’

‘No, I don’t think I do.’

He says where Appian Terrace is and how he came to get the room there. He says that Mrs. Biddle is bed-bound, how he’s worried about the teapot because the stuff is unravelling off the handle, how she could have a fall. He puts down Cat Scat because a cat comes that’s a nuisance to her. But it isn’t any good.

‘Mrs. Biddle has her memories,’ he says. ‘Theatrical.’

He can see the photograph Pettie was on about, the plain dress with the collar up a bit, the woman who’s in the grave they haven’t erected a stone for. There was an accident once on the April outing, a red car squeezed shapeless, hub-caps and metal on the road, the radio still playing, no chance. That comes into Albert’s mind, but he doesn’t mention it. Too much speed, Joe Minching said, and they got out of the minibus at a Services and watched the speed, everything going by below them on the motorway, reds and greens and blues. ‘More blues,’ Ram said, and Leeroy argued.

He’s offered the biscuits again and takes another, the chocolate heart. He tells them about the Underground because she asks if he has work. He remembers Pettie saying you could hardly see the make-up on her face and he can hardly see it today either. Mrs. Biddle puts lipstick on first thing, then her powder.

‘Little Mister’s with the rent boys,’ he says, and he watches a sadness coming into her face. He likes her clothes and the way she stands so straight when she’s on her feet, and the softness in her eyes. He liked her the minute she held her hand out to him, smiling then too, giving her name. He tells about Little Mister left on the step and how he got to be called that. He tells them he heard from Merle one time that Mr. and Mrs. Hoates were down Portsmouth way now.

‘Running an old folks’ residential.’

She asks about Merle, and he says she’s not around these days, not since she went up Wharfdale. Nor Bev, he says.

Darkened by the rainfall, the drawing-room is invaded by other people and another place, by the faces of children, black and white and Indian; by dank downstairs passages, Cardinal polish on concrete floors, a mangle forgotten in a corner; by window-panes painted white, bare stairway treads, rust marks on mattresses. A handbell rings, there is the rush of footsteps.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death in Summer»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death in Summer» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death in Summer» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.