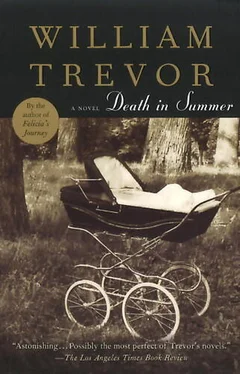

William Trevor - Death in Summer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Death in Summer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death in Summer

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death in Summer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death in Summer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death in Summer — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death in Summer», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘No, we never did.’

With encumbrances, they wouldn’t have held a position down. They’d have to have gone for a different kind of house right from the beginning. He explains this, passing the time for her because it’s what she wants. Her voice is empty, but she keeps the conversation going.

‘This was the work you chose? Both of you?’

‘We met through the work. When the times changed we went as a couple because couples were the thing then. Zenobia picked up the kitchen knowledge, although lady’s maid she’d have preferred, upstairs being what she knew. Beggars can’t be choosers.’

‘My daughter thought the world of you both.’

‘She was the soul of kindness, your daughter.’

‘I’ve let her down.’

‘She’d be the last to say that.’

The tray is as he has placed it. She hasn’t poured her tea. She stares at the prickles of a plant he considers unattractive. Ripening fast, the grapes hang all around her. It’s hard to imagine, she says, that anyone wouldn’t stop to think before causing such distress.

Greed takes care of that, Maidment refrains from stating. It was greed that possessed an illiterate foreigner when he hatched his plot, fear that caused him to commit his more terrible crime. When greed and fear get going, who stops to think?

‘I would pay anything,’ she says, and Maidment can think of no suitable rejoinder. He pours her tea for her, handing her cup and saucer. A sudden longing to have a cigarette stirs in him. The dog is restless, he says, and takes her with him to the darkened garden.

‘Still we’ve never been to Scarrow Hill,’ Zenobia hears herself remark, and then they’re there. In the picnic area she spreads out the lunch-time fare, bread and salad, meat-loaf she made herself. Exposed on spongy hillside turf, an outline of grey rock depicts a giant.

She wakes abruptly. Around her on the kitchen table is the brass she has collected from all over the house, and Duraglit and cloths. There’s the silver, too: the ornamental pheasants from the dining-room, sugar-casters, toast racks and cutlery, the silver eggs that came from Poland, the Polish crucifixes. An hour she has spent already with the Duraglit and Goddard’s; before that she rearranged the tins and bottles on the cold-room shelves, and washed the passage and the cold-room floor. It’s five to three now.

She blinks and rubs her eyes, dragging herself back to fuller consciousness. There was a nurse who killed babies. Four babies, maybe more. A woman pretended to be pregnant, preparing her neighbours and her husband for what she intended to do, but when she got the baby she neglected it and it died. Other babies were taken in order to be tortured and afterwards a woman sought forgiveness, pointing out the burial places.

‘You take it easy, madam,’ the police officer who did the talking sought to soothe her when her voice rose anxiously in answer to a question. Strong tea, he advised; and counsellors were available. But prayer is Zenobia’s way. As drowsiness is dispersed, she prays again.

‘A Mrs. Ferry died tonight.’

At the sound of Thaddeus’s voice, Rosie lumbers to her feet, yawning and stretching herself again. The window Maidment opened earlier is closed now. In the conservatory only a single table lamp is lit.

‘That was the telephone call?’

‘Yes.’

He watches her nodding: she isn’t interested. In the brief, unemphatic motion of her head there is the weariness of defeat, as if time, by simply passing, has drained her of everything but this fatigue. Standing until now, Thaddeus sits down in the second wicker chair. Rosie comes to him, to rest her chin on his knees. He strokes her head.

‘There’s been nothing since,’ she says.

‘I’m sorry I went away.’

‘You looked for her?’

He shakes his head. There was panic in his restlessness; he ran away from thought, but of course you can’t do that. Talk is a help: in the last few moments he has discovered that. Any words, it hardly matters what they are, and the effort of releasing them: had he gone into the Old Edward, he might have stayed for ages.

‘I have never been so afraid,’ she says.

‘Nor I, I think.’

Zenobia is with them, as suddenly and as silently as an apparition. She has heard their voices, she offers coffee, or tea again. She picks up the tray on which her sandwich has not been touched, tea poured out and left. Thaddeus says:

‘You should go to bed, Zenobia.’

‘I’m better up, I thought.’

When she has gone he says: ‘I feel I am being punished.’

There is no response, but even so he continues.

‘Mrs. Ferry was a woman I ill-used. I had a peculiar childhood.’ It left uneasiness behind, he says, and tells her about that. ‘I have never trusted people. You were right to be doubtful: the untrusting are untrustworthy.’

‘I was ungenerous. I rushed in foolishly, as if your marriage were somehow mine to order.’

‘Your lack of generosity is more kindly called perception.’

‘I don’t think I said at lunch-time that I have come to understand why Letitia loved you.’

‘I was the last of her lame ducks. There was a bargain of some kind in our marriage, in the giving and the taking. But gradually it got lost, as if all it had ever been was a means to an end. I would have given half my life then to have loved Letitia. Today it will begin, I used to think. In some random moment of the morning, or after tea, or when we’ve gone to bed. But it never did.’

‘All that does not belong now.’

‘It is something to say.’

‘Why do you not blame me?’

‘Blame does no good.’

Vaguely, she nods again, the same tired gesture ofacknowledgement, not up to conversation. Thaddeus turns off the lamp on the table, and the conservatory is more softly lit by the haze of early morning. He does not want this day, so gently coming. He does not want its minutes and its hours, its afternoon and its evening, its relentless happening.

‘A miracle it has seemed like,’ Mrs. Iveson hears him say, and is confused until he adds: ‘Loving Georgina.’

She dreamed of Scarrow Hill, Zenobia says, and Maidment remembers from his own sleep a raw-faced bookie in a jaunty hat, and polka dots and hoops and jockeys’ chat, Quick One at nines, K. McNamara up. There was, before or after that, her wedding-dress hanging on the wardrobe door, his carnation in a tumbler by the wash-basin. There was his own voice singing ‘Drink To Me Only’.

‘It was to say a woman died,’ Zenobia passes on. ‘That phone call that came earlier.’

‘What woman?’

She gives the name. Bleary, he feels he’s dreaming still. Not quite in the kitchen yet, but hovering in the doorway as he sometimes likes to, he averts his head to belch away a little air. Slowly he advances to the table and sits down.

‘What’s this then?’

‘I looked in at the conservatory to see if anything was needed.’

‘They’re there?’

‘And have been a long while.’

‘So Mrs. Ferry’s passed on her way?’

‘Dead was what I heard.’

‘Mrs. Ferry was the woman quarrelled over the afternoon of the accident.’

‘You said.’

Each time she passed through the hall, returning the brass and silver pieces to their places, Zenobia says she heard the voices continuing in the conservatory. It not being her place to listen, she didn’t do so. What she heard about the woman there’d been the quarrel over was said when she looked in to see if anything was needed.

‘I dropped off a second and had that dream about the Scarrow Man.’

‘I doubt my eyes closed,’ Maidment touchily retorts, annoyed because it seems he might have passed the hours more profitably. He woke up and saw the other bed empty. Someone took the baby, he remembered then.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death in Summer»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death in Summer» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death in Summer» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.