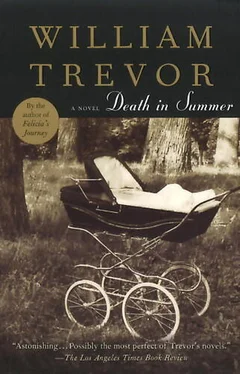

William Trevor - Death in Summer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Death in Summer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death in Summer

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death in Summer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death in Summer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death in Summer — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death in Summer», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘We’ll go, Tadzio’: his mother saying that comes back, as if from her limbo she seeks in this cruel time to make amends, to rescue from it the child she never knew a man, nor ever knew at all. Through Metz and Kaiserslautern and Berlin, her long white finger first traced their journey to the country he had invented from her scraps: ships and sails on a frozen sea, her remembered street lamps of brightly decorated metal, coal dug out with a spade. Eva Paczkowska she showed him, handwritten on a certificate he could not understand, and in a photograph she pointed at the house where she’d been born. At a café table she had looked up and for the first time saw his father, his fur hat on a table by a coffee percolator, his hands held back from the red-hot metal of a stove. ‘Tadzio, you were born that day.’ Born because of the love that began in the fug of a coffee house, because his father had come to her cold, dark country to sell soap.

‘Look, Tadzio!’ But it was still his father, not he, she pointed for — at St. Hyacinthus’ Church, at all the sights of Lazienki. ‘Palaces! Palaces!’ his father had exclaimed. ‘How many more, for heaven’s sake!’ The Blue, the Primate’s, the Archbishop’s, the Pac, the Raczyski, the Krasiski, the Palace upon the Water. ‘Kanapka,’ an old sandwich-seller offered, opening a sandwich to display its contents, which years ago she had done for his father too. There was the restaurant where his father first ate nalesniki, the florid waiter no more than sixteen then. ‘Oh, what happiness it was!’ And strangers in Eva Paczkowska’s city listened to the story of the Englishman who once came to Poland, who gave a Polish girl, in return for Poland’s gift to him, a quiet English house, cherry trees at each corner of a garden.

Thaddeus passes the Old Edward by. He tries to hear his mother saying a tailor sat cross-legged in that window, to hear her telling him that jajko is egg and kawa coffee, making him repeat Górale mieszkaja w górach. But the distraction does not hold. Still warm, the air is drily odorous, a smell of old dust and buildings. Litter has gathered in the gutters and neglected doorways. Street lights are dim, as if the neighbourhood deserves no better.

He has not come to this nowhere place with hope, but only to escape all that his house is now. Tonight it’s inconsequential that his beautiful mother used up her love in comforting an invalid of misfortune and of war. Or that his father sighed and only wished to be alone with her, his body shivering in a bout of pain.

Divers will go down. They’ll go down to the murk, to old prams and supermarket trolleys, wheels of bicycles, parts of cars, the rotting shells of boats. In their ugly wet-suits they’ll search the slime, fish streaking about them, dead flotsam disturbed. They’ll root among the weeds and clumps of rust. They’ll lay out rags of clothing on the riverbank and gaze at them, and nod.

Thaddeus calculates: his child has lived for a hundred and eighty-eight days.

A ladder was placed beneath the nursery window; in a matter of minutes the baby was gone. When he heard, Al Capone offered a reward, knowing how he’d feel himself, he said. Twenty-five thousand dollars Lindbergh earned for flying the Atlantic, common knowledge at the time.

‘I would ask you not to,’ Zenobia requests. ‘It doesn’t help.’

A riposte comes swiftly to her husband’s lips but is not issued. An hour ago, when he walked to the end of the drive, he saw the lights of two police cars parked a few yards away and there was chatter coming from a mobile phone. In the early morning, unless there has been a discovery in the night, the search will begin again with local help. Farm labourers will form a line to beat the undergrowth and walk the woods. They’ll rove the harvest fields.

‘First light,’ Maidment predicts.

Zenobia waits for the water in the electric kettle to boil, emptying away what she has heated the teapot with. She makes the tea, then slices a tomato. She thought of making toast, buttering it and cutting it into fingers, but decided on a sandwich instead. It’s hard to know what to prepare for someone at a quarter to twelve at night, someone who’s sick with worry.

‘She said she wanted nothing,’ Maidment reminds her, ‘and he’s not back yet.’ The Lindbergh ransom sum was twice as much as the twenty-five thousand, but they had it and they paid it, not knowing that their baby had already been murdered. An illiterate German immigrant the abductor was.

‘She can’t want nothing for ever. It could be I should sit with her.’

‘She has the dog, of course.’

An hour ago he heard Mrs. Iveson moving about. She went from the drawing-room to the conservatory and was settling down there with the dog when he went to ask her if she needed anything. He opened a window for her.

‘I’ll take the tray in. Look in yourself, why don’t you, before you go upstairs? If she wants company she’ll say so.’

‘I couldn’t go upstairs tonight.’

Maidment, who intends to retire in the usual way, refrains from arguing that rest offers strength, and takes his jacket from the back of a chair. Rhymer the name of the elderly butler who knew about the Lindberghs was, Rhymer who touched the port and suffered for it. The old man’s knotted features appear in Maidment’s recall, the addled look that had developed in the bloodshot eyes. Gout and worse affected him in his work and they found him early, passed away quietly in a lavatory the night before. The pantryman was next in line for the position.

‘Nothing can be done but wait.’ Picking up the tray, Maidment satisfies himself with the observation. The Lone Eagle they called Lindbergh after his Atlantic flight, Rhymer said. The German was a jobbing carpenter, trusted in people’s houses.

‘I couldn’t,’ Zenobia repeats, filling the kettle again for the kitchen tea. ‘I couldn’t lie there sleepless.’

‘I’ll chance it myself for a while.’ For all they know, it could have been on the News, but sometimes of course the police will keep quiet for reasons of their own. Maidment pauses at the door, about to mention the News, but decides against that also.

‘I brought you something, Mrs. Iveson,’ he says in the conservatory. He hesitates for a moment, since this is going against her wishes, neither tea nor food requested. Disturbed by his entry, the dog stands up and stretches.

‘That’s kind of you, Maidment.’

‘It’s just a little.’

‘Thank you.’

She’s always polite and civil. She’s distant, but that’s her way; getting to know her, you come to understand that. A different manner of shyness in mother and daughter; less than a week ago he remarked on that.

He clears a space for the tray and pulls the wicker table a little closer to her. She has been waiting for the telephone in the hall to ring: you can tell that from how she is.

‘All we can do,’ she says.

The Lindbergh family was never the same again, Rhymer said; you had money, you had trouble; they took it from you, they killed you for it. Servants to money, the well-to-do were: when it came down to it, everyone was a servant, Rhymer maintained, unaware that most of his utterances were taken with a pinch of salt.

‘I can’t believe it was just some woman walking by. Do you think it was, Maidment?’

‘It’s hard to know what to believe, Mrs. Iveson.’ The trouble with a woman who’d take a baby, she could be a mental case. Without a shadow of doubt, the man who climbed up to the Lindberghs’ window was what they’d call a nutter nowadays.

‘You never had children, Maidment?’

She surprises him, asking that, and the question coming so suddenly. There is an intimacy in the query, as if what has happened this afternoon has changed their relationship, as if formality no longer makes sense.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death in Summer»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death in Summer» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death in Summer» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.