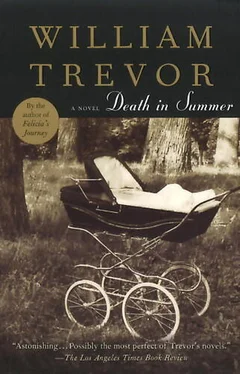

William Trevor - Death in Summer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Death in Summer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death in Summer

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death in Summer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death in Summer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death in Summer — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death in Summer», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘And people use this path?’

‘Not much.’

It was a short-cut from the house in days gone by, Zenobia says. ‘It seems they went to church that way if they wanted to walk in summer.’

‘So it’s not your experience, sir, that a passer-by might open that door and come into the garden, maybe making a mistake?’

‘Never.’

Zenobia points out that a passer-by would have no right. Sometimes a cat comes into the garden. Or a dog, not on a leash, is called back from the drive. Now and again a car comes up the drive, and goes away when it is realized that this is the wrong house. That’s not often, probably less than once a year.

‘Mr. Davenant’s a widower, I understand?’

Surprised, Zenobia wonders why this is mentioned. The way he puts it, the man knows already. Everything like that would have been established in the drawing-room. Maidment says:

‘There was a road accident. Not long ago.’

The policeman nods. A flicker of interest passes through his expression, a frown gathers and then is gone. The news was broken by the police, Maidment says. The news about that accident.

Listening to her husband giving the details, Zenobia is aware of the same sense of connection that Mrs. Iveson has experienced in the drawing-room, and it feels like mockery to her that there should be this second cruelty, drifting out of the summer blue, as the first did. Maidment’s thoughts are similar, then are invaded by a famous episode in the past — the taking of the Lindbergh baby. It was before his time; what he recalls is hearsay, supplied to him by an elderly butler of the old school who enjoyed such titbits. If that’s what this is there’ll be a message in the morning, the words cut out of a newspaper and pasted up: used banknotes to be secreted in a rubbish bin or a telephone-box or the cistern of a public lavatory, a specified place, a specified time.

‘If contact is made after we’re gone,’ the policeman says, ’I’ve told Mr. Davenant and the lady we’ll need to know at once. While we’re still here don’t answer the phone until we’re in a position to monitor the call.’

‘You think they’re after money?’ Zenobia inquires, and hears that at this stage it’s important to keep an open mind.

‘It’s equally possible we could be looking for a local woman. Is there anyone at all you can think of, a woman who got to know the routine of the house through observation? A frustrated would-be mother, an older woman it often is, though by no means always. Someone who saw the opportunity and took her chance?’

There’s no one they can think of, but for Zenobia the thought of a woman taking her chance is preferable to brutish men. Years ago at Oakham Manor a gang got in. They silenced the alarm and poked a kitchen grab through a fanlight, drawing back the bolts with it, even lifting the key from the lock. Every scrap of silver gone, and never established how it was they knew where to look for it. Zenobia still shivers with apprehension at the thought of men with shaved heads roaming about a house at night. It was she who found the back door swinging the next morning, she confides to the bulky policeman, and had to break the news on the telephone to the Hadleighs, in Austria at the time.

‘Yes, it’s unpleasant, Mrs. Maidment. But I’m afraid what we have here is more unpleasant still, no matter who’s responsible. So no local person comes to mind?’

‘No one at all.’

‘I’d hardly say it was local,’ Maidment contributes. ‘I’d lay my bones down there’s money in this somewhere.’

Zenobia notices a moment of surprise in the policeman’s features, occasioned by the expression used, but when he speaks he is impassive again.

‘As I say, sir, we have to keep an open mind. But of recent times it’s been women who’ve been helping themselves to babies.’ A while back, they may remember, a baby born only a few hours was taken from a hospital ward. Another time, a baby-minder who ran off in Camden came to light in County Limerick. In this day and age, if a woman has a fancy for a baby she takes what’s going.

‘Even so,’ Maidment persists, ‘I’d say we’re talking ransom money.’

‘That’s not discounted, sir.’

‘We had those phone calls,’ Zenobia says, suddenly remembering.

‘And what were they, Mrs. Maidment?’

‘Someone ringing up and not saying anything.’

‘When was this?’

‘They began a couple of weeks back. You’d answer and the receiver’d be put down.’

‘I see.’

WPC Denise Flynn and her colleague return. The door in the wall was open, Denise Flynn reports, not wide, but a little. The ground’s too hard to carry footprints, her colleague says.

‘Usually open, that door, Mr. Maidment?’

‘Never.’

‘Most likely that’s the way they came and went. A couple it could be.’

The rooks swirl above the oaks and the house. Climbing or diving, they caw and screech, observed by two silent buzzards, motionless in the air. Below them, another police car arrives.

The garden is searched for a sign left behind by an intruder or intruders, but there is nothing. Local houses are visited. Increasingly favoured is the theory that a motherless baby has become the prey of a woman with an obsession about her own maternal needs. In low voices the likelihood is repeated in the police cars as evening settles over lanes and fields, and the inmates of farmhouses and cottages are disturbed.

‘Yes, it may be that,’ Thaddeus agrees when the notion about a woman of the neighbourhood is put to him. There is nothing he can add. He has known the women of the neighbourhood all his life. Some he has known as children, seen them becoming girls, those same girls marrying and having children of their own. When asked about the peculiar or the unusual among them, he mentions Mrs. Parch, who claims to possess the power of healing, who has been making a profit from the exercise of her skill for sixty years. Visitors still come to her cottage to receive the benefit of her gifted hands and to hear her daughter, Hilda, read a report in a local paper when the phenomenon was contemporaneously recorded. Hilda herself has chalked up a success or two with herbal remedies: a decoction of grasses and the juice extracted from comfrey for gastric ailments and arthritic joints. But neither Mrs. Parch nor her daughter interests WPC Denise Flynn, who has been assigned the task of gathering information about the women of the locality.

‘There’s Abbie Mates,’ Thaddeus remembers also. A younger woman, a fortune-teller at summer fêtes, reader of the Tarot cards. And there’s Melanie, who lives alone by an old railway crossing and regularly bears the children of a man who visits her. But they, too, fail to arouse the policewoman’s suspicions.

Further questioning reveals that among the house’s usual visitors two charity women came recently for Letitia’s clothes, and Jehovah’s Witnesses have been, and a girl to search for a ring she dropped. Hoping to get rid of a load of tar, a man called in, offering to resurface the drive at a bargain price. Burly, black-haired, a stutter coming on when his sales pitch became excited: every detail remembered is of interest and is recorded. ‘They showed you literature and that?’ WPC Denise Flynn prompts. ‘The Witnesses?’ And bleaklv Thaddeus nods.

The white police cars go eventually, with fresh instructions left about a possible telephone communication. ‘Someone knew,’ Zenobia concludes in the kitchen. ‘Someone knew we have an afternoon rest ourselves, and saw the car drive off.’ She blames herself, as Mrs. Iveson does, but Maidment is dismissive of any misdemeanour on his wife’s part or on his. Half an hour only they lie down for, he reminds Zenobia, and in the half-hour today he didn’t close an eyelid. The newspaper dropped to the floor, he grants her that, but he did not sleep. Anything untoward he would have heard.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death in Summer»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death in Summer» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death in Summer» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.