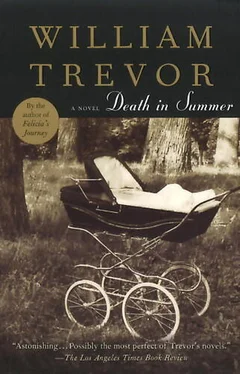

William Trevor - Death in Summer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Death in Summer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death in Summer

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death in Summer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death in Summer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death in Summer — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death in Summer», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Hinchley the gardener was called. His scar stretched from wrist to elbow because while an enemy soldier was inflicting it he was shot and fell forward, bringing this Hinchley to the ground with the bayonet trapped in his arm. After he’d shown the children his wound Hinchley always had a smoke apparently, a small, charred pipe for which he pared tobacco from a plug.

‘Stories hang about old family houses like ghosts.’ It was his mother who told him all that about the gardener; his father didn’t tell stories much.

‘Letitia kept a diary when she was little,’ the grandmother gets her say in.

‘Yes, I know.’

‘It’s interesting about the summer-house.’

You can tell she isn’t interested in the least, even though she has said she is twice. She has wangled her way into the house, pulling the wool over his eyes with her talk. He was referring to that other diary and she has to bring Letitia into it, harping on the name when he’s trying to forget it in his grieving.

She’s on about a shoe now, a heel coming off when Letitia was little and Letitia not minding when she had to walk in her bare feet on a street. There’s something about how Letitia went in for music, how she always had music going apparently, how she couldn’t be without it. He makes some comment on that, but his voice is too low to carry.

‘Well, I must go and see if my charge has woken up,’ the old woman says.

Dismally, Pettie watches while he pats the dog’s big brown head, the way he’s always doing. A blackened tennis-ball falls by his feet, a paw prods his trousers. There’s foam on the dog’s tongue and when the ball is thrown it’s carried back again and dropped at his feet.

‘Thaddeus.’ She says his name, louder than a whisper. Each day going by and the old woman still not here, she thought there was a chance. Just by looking at the old woman you can see it: anything goes wrong she’ll be all over the place.

The ball is pushed against his shoe when he takes no notice. The dog’s fond of him, standing back and barking now. Letitia’d never want it, an inadequate tending Georgina Belle. Grandmother or not, well longer than thirty years it would be since she tended a baby.

She says his name again. She wants to push the door wide open and go to him. She wants to tell him she knows he’s hurting, to tell him she put the flowers there. She wants to tell him what Letitia would, that the baby isn’t properly minded, that the baby isn’t safe.

She watches while he smiles down at the dog. He throws the ball again, skittering it over the grass, and her longing is more than she can bear. She closes her eyes and his voice whispers between his caresses, saying he knows too well the old woman shouldn’t be here. His fingertips are light on her skin, and on her lips when he whispers that it is their secret, that they have always had a secret, since the first day she phoned him up, that everything in the end will be all right. His arms hold her to him. He whispers that a thing like this can happen. He calls her his princess.

6

‘You read that?’ the red-haired proprietor of the Soft Rock Café asks, jerking a thumb at the newspaper open beside him. ‘They got that car-tyre guy.’ A car-tyre vandal, he says, eighteen hours’ community service. A pound thirty-eight, he says, returning his vast metal teapot to the electric ring on which he keeps it hot. ‘There you go,’ he says.

Albert carries a glass mug of tea and one of coffee to a table and returns to the counter for the doughnuts. He puts a saucer over Pettie’s coffee because she hasn’t arrived yet. He didn’t order her coffee, the man just set his machine going and put her doughnut in the microwave, maybe thinking she was outside on the street. Albert doesn’t drink coffee himself, having read in a newspaper that it doesn’t do you any good.

‘What I’d do for vandals,’ the red-haired man calls across the café, empty of customers except for Albert and the dumb man in the window, ‘is bring the stocks back. Coat over the head’s the first thing any villain wants. Know what I mean, Albert?’

Albert says he does, and hears about a young bloke beaten to a pulp when he wouldn’t give two other blokes a bag of crisps. ‘I’d have the cat o’ nine tails back, Albert. Electrically operated, no call for anyone to demean their-selves working the cat this day and age. Know what I mean?’

Albert again says he does. Pettie doesn’t like the red-haired man. He called her pert once; he said she’d fit into a thimble. Pettie complained that that was familiar, and Albert worries that something similar may have again offended her, that she may have come in on her own and taken exception, that because of it she won’t come this morning. In Mrs. Biddle’s house she comes and goes when he’s asleep, or at night when he’s at work; half the time he doesn’t know if she’s there or not.

‘You see Pettie around?’ he asks the man, going back to the counter to do so.

‘She ain’t here yet, Albert.’

‘She been in though?’

The man says no, not earlier, not yesterday, not the day before. He’d set the stocks up outside Burger Kings and Kentuckys, outside pin-ball joints, and toilets, in car parks — wherever people go by he’d have them. ‘Settle their hash for them, languishing in the rain.’

When she arrives she starts the music. She lifts the glass saucer from her coffee. Ignoring the raspberry doughnut that has been heated up for her, she lights a cigarette. She’s wearing a different T-shirt, yellow with music on it.

‘You OK, Pettie?’

She doesn’t answer. She doesn’t nod or shake her head.

‘You got work then?’

‘I feel for him, Albert.’

Albert looks away. He stares at the matador in one of the posters, then at the bull, head bent, horns ready to attack.

‘I’ve been going out there,’ Pettie says.

‘The man with the baby, Pettie?’

‘All the time I feel for him.’

Albert shifts his glance, allowing it to fall for a moment on the excitement that brightens his friend’s features, her eyes lit with it behind her glasses. Distressed, he surveys the similar bull and matador of the poster on the opposite wall, then asks:

‘You going to eat your doughnut today, Pettie?’

She shakes her head. She eases the wrapping from her cigarette packet and begins to make a butterfly of it. Albert watches her fingers twisting the transparent film. He asked her once who taught her how to make the butterflies, but she said she taught herself.

‘He’s old, Pettie. You said.’

‘Forties. Why’d it matter?’

Her cigarette smoulders in the table’s discoloured ashtray, a thread of smoke floating lazily from it. The man in Ikon Floor Coverings was older too, fifty or so, Albert guessed. A tired face, she said. Albert remembers that although he never met, or even saw, the man. ‘It could be he’s gone off sick,’ she said at this very table, before she discovered the man had moved on to another store.

‘Every day I go out there.’

She tells about the difficult journey, the trains that are few and far between. Twice she’d had to thumb a lift on a lorry. The bus from the station goes round the long way and an hour it can be, waiting for it. You get there quicker if you walk by the drained canal. You turn away from the towpath when the spire of the church appears; you come out by the shop.

‘You shouldn’t go thumbing lifts, Pettie.’

‘You have to, morning time.’

The lorries go down Romford Way, out beyond the Morning Star. Ifyou get there early they’ll stop. She wouldn’t take a lift in a car.

‘That man going to give you the job out there after all then?’

As old as Mrs. Biddle, the grandmother is. No more’n a laugh, Mrs. Biddle minding a baby. The grandmother’s got herself in there like she said she would.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death in Summer»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death in Summer» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death in Summer» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.