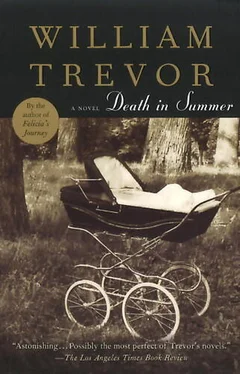

William Trevor - Death in Summer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Death in Summer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death in Summer

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death in Summer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death in Summer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death in Summer — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death in Summer», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘You’ve never known unhappiness, darling,’ her own voice echoes, sounding harsh although she did not intend it to. In marriage she had not known unhappiness herself, and simply feared for her daughter in uncharted territory. That on an April afternoon there should have been an encounter on a train was a chance as cruel as life uselessly passing in a twilight room. You can’t help loving someone, Letitia said, returning at her usual time from the music library less than two months later, not taking her coat off yet or putting down her handbag. And that was that.

Standing on a chair, Mrs. Iveson reads the electric meter. Kneeling down, she reads the gas one. She notes both figures and leaves the piece of paper on the kitchen table, asking the Redingers to check them. On the radio a programme about people who collect things begins, a woman in Pontefract with an assortment of dental plates, a man with light switches, another with beer-bottle tops. She turns the voices off, realizing that she should have done so before reading the meters but deciding that a minute of the radio won’t make much difference to the figure she has recorded.

She closes her kitchen door and sits down to wait by the window of her sitting-room. She gazes into the street below, where a smartly dressed tart is exercising her Pekinese. Not long ago she was taken for such a woman herself as she let herselfin at the downstairs door. A man with a moustache in a teddybear coat raised his hat. ‘Colette?’ he smiled. ‘I phoned.’ This trade, in daytime, is a new thing in the neighbourhood.

The woman and the dog pass round the corner and then Thaddeus’s car appears, his old blue car to which apparently he is attached. Letitia found that touching, as she did his attachment to his house and to his garden. A sentimental man, she said. The worst that could happen next was that unhappiness would come. Beyond imagination was what actually occurred.

The car is parked. Returning quickly, the woman with the Pekinese smiles. Thaddeus shakes his head. ‘Oh, don’t be silly,’ Mrs. Iveson vexedly upbraids herself. She blows her nose and crosses from the window to a looking-glass. She tidies her hair again and then is ready.

‘Small mercies,’ Maidment commented when it was decided that a nanny was not to be added to the household, and Zenobia unhesitatingly agreed. A sense of satisfaction — almost of celebration — has since prevailed.

For, old or young, such women have been a bane. Nanny Tub, remembered without pleasure in a house in Somerset, belonged to a regime that lingered from the past, an imperious termagant, disdainful and cantankerous as of right. Her replacement, when finally a replacement was considered necessary, complained that she’d been given catfood in a shepherd’s pie. Another wouldn’t touch meat in any form and had to have Oriental vegetable dishes prepared for her. A third took garlic in quantity for her health, its odour trailing behind her from room to room.

‘We have to see, of course,’ Maidment concludes, caution in his tone, ‘how madam deploys herself.’

A racing paper, folded in two, lies between the couple on the scrubbed-oak surface of a table that is as strong as a butcher’s block and as steady. It is all that remains of the kitchen as once it was: the black-leaded double range has gone, as have the ham hooks from the ceiling, the row of bells, the stone flags from the floor. It is a modern kitchen now. Working surfaces are pale moulded laminate, wall cupboards finished to match; deep-freeze and refrigerator, cooking hob and oven, dishwasher, tumble-drier and washing-machine are unified through shape and colour and design of detail. But the oak table still retains its slab of white marble set in the timber at one end, for many generations an aid to bread- and pastry-making.

‘I foresee no troubled waters.’ Zenobia rises from the table as she speaks, gathering up the cups from which mid-morning tea has been drunk, the brown kitchen teapot, jug, sugar bowl, and a plate with only the crumbs of a cake left on it. She stacks these dishes on a tray and carries the tray to a draining-board, where she separates them: milk and sugar kept to one side, the teapot rinsed beneath a running tap, everything else placed in a washing-up basin in the sink.

‘Death is a trouble in itself,’ Maidment remarks, which is a repetition voiced regularly since the tragedy, for when Maidment discovers a phrase he considers apt he is generous in his use of it. ‘The good go quietly from us,’ he quoted on the day of the funeral, the observation overheard in another house on a similar occasion.

‘Life must go on,’ Zenobia retorts through the rattle of dishes.

‘I grant you that, dear. It’s not grief’s function to obstruct it.’

Shocked and sympathetic, the letters coming to the house have been read by Maidment, the daily stack of answers taken by him from the table in the hall to the postbox. ‘I cannot help myself,’ Zenobia apologized often during that time, weeping as she did her work. The will that was read left the couple a nest-egg substantial enough to allow eventual retirement without restriction. On that score, too, Zenobia’s tears have been shed.

‘I’m heating your milk, dear,’ she addresses the baby, in her care this morning, while Mrs. Iveson is fetched.

Sleepily occupying the pram that is her blue-and-white and most familiar world, incapable as yet of articulating more than private sounds, Georgina does not respond.

‘Never a hope they’ll get on,’ Maidment pursues his reasoning, ‘and of course were never meant to.’

‘They’ve put our young friend here before their differences. You can’t but admire that. There’s been a side brought out in both of them.’

‘I wouldn’t go a bundle on admiration. I wouldn’t put money on a side brought out.’ Maidment draws in air, his lean nostrils tight for a moment in a way that is particular to him. He releases them while glancing at a line of print, noting that It’s the Business, K. Bray up, is favoured if the going doesn’t turn heavy, which is unlikely. Major Mack gives Rolling Cloud, P. J. Murphy’s Guaranteed Good ‘Un is Politically Correct. He favours The Rib himself.

‘One minute and it’ll be ready, dear.’ Zenobia smiles with this annunciation, hoping that Mrs. Iveson’s advent will not deprive her entirely of the baby’s company. She tests the milk and returns it to the bottle-heater, considering it not yet warm enough. The survivors share the burden of a child: that’s what there is; the rest is wait and see. She does not press her conjecture of a moment ago, but deliberates instead. He has his ways, he has his right to an opinion. Servitude has made him what he is and has — though differently — made her. All that, Zenobia accepts, and expects no more of their calling. Childless themselves — as so often and so naturally their predecessors in this kitchen have been — they are a couple who hang on in whatever households they can find. They are out of their time, which was a time when servitude had a place reserved for it, part of what there was. Their lives are cramped as much by this as by the exigencies of domestic duty, yet on neither count do they complain. They have chosen this; they have sensed the stirrings of vocation in serving the remnants of nobility or the newly rich. They have found a place in the great houses that are now the property of popular entertainers, that are now hotels and schools and residential business centres. They have visited on their Sundays off places of local interest in the many counties of their employment, this in particular being Zenobia’s relaxation: Lydford Gorge and Mount Grace Priory, cathedrals and gardens, the narrowest street, the oldest tower clock. As they are presently settled so they hope they may remain, not moving on until age gets the better of them.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death in Summer»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death in Summer» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death in Summer» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.