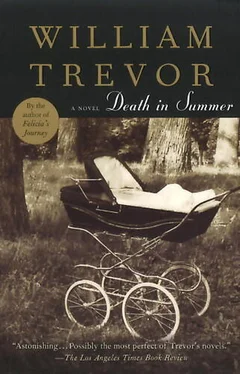

William Trevor - Death in Summer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Death in Summer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death in Summer

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death in Summer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death in Summer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death in Summer — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death in Summer», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘And it may not,’ Zenobia answers her own reflection, testing the temperature of the milk, squirting a drop on to her wrist. ‘We trust in Providence.’

In The Rib more like, Maidment’s thought is: O’Brien the trainer, The Rib will take some beating. Maidment has never been on a racecourse: what he knows, all he experiences of the turf, is at second-hand, but second-hand is enough. Epsom and Newmarket, the Gold Cup, the Guineas, the sticks, the flat: it is enough that they are there, that sports pages and television bring them to him. Rising from his chair, folding the newspaper away, he softly hums a melody he danced to as a boy, and prepares to go about his morning tasks, vacuuming and airing and dusting, setting things to rights. He tolerates old clocks and narrow streets, he does his best in gardens and in stately rooms that do not interest him. Other people’s lives, how they are lived and what they are, offer what the vagaries of the turf do: mystery and the pleasure of speculation.

Zenobia hears the humming of her husband’s tune continue in the kitchen passage and abruptly cease when he passes through the door to the hall. As he is unmoved by what she most enjoys, so she is not drawn to the excitements of the racetrack; and mystery for her is the mystery of the Trinity. Every night and morning she prays on her knees by her bedside; on Sundays her husband waits in their small red Subaru with the News of the World, while she attends whatever church they pass on their way to a place of interest. Disagreement between them no longer becomes argument, resentment does not thrive. Give-and-take patterns the Maidments’ middle age; they go their ways and yet remain together.

‘Oh, it is better so,’ Zenobia comments, offering the opinion to her employer’s child.

In the small room that opens out of the bedroom in which Thaddeus Davenant was born are the personal possessions he has kept by him, and photographs and papers. For the five years of his sojourn in this house Maidment has repeatedly examined them, expertly poking about in drawers and in the pigeon-holes of a writing desk, anywhere that is unsecured. Box-files are marked Insurance, Receipts, Bank Statements, Accounts. In a flat tin that once contained mint sweets there are keys that have never been thrown away, old fountain-pens, old watches, a yo-yo, an empty notebook, cufflinks separated from their match, tie-pins, dice, marbles. A shallow drawer is full of half-used seed packets. A silver hip-flask bears the initials P. de S. D., and at the wheel of a sports car is a genial man whom Maidment has long ago recognized as the initials’ source. He it was who attempted to resurrect the family’s past by manufacturing soap instead of the tallow that for generations had made its fortune, travelling the countries of Europe in search of orders. Pasted into an album now, he’s there among trams and motor-cars in Vienna, and again in Amsterdam. He skates with a tall, beautiful girl on a frozen lake, is with her among the wild flowers of a hillside. Maidment knows her well: Hitler’s war came, Eva Paczkowska was brought from Poland to England in the nick of time. Still beautiful, she stands smiling by the summer-house. Still beautiful, she’s on the front-door steps, holding a child by the hand. But beside her the genial man she married is cadaverous now.

Maidment has searched but has never found snapshots of that child growing up. The camera seemed to have been put away. Only among the gowned ranks of schoolboys, framed on the room’s dark wallpaper, is there a face he recognizes, reticent and private at that time.

Some tidying has taken place, he notices this morning. The wastepaper basket is full, papers that have accumulated since the death are no longer in a bunch beneath the bronze horseman on the windowsill. Cheque-book stubs indicate payments made that were not possible a week or so ago, before a simple probate was completed. Correspondence from solicitors has been relegated to a relevant file, letters of condolence ticked when they’ve been answered. The hiatus is over, the debris of death disposed of. The woman who asked for money has been visited, faith kept with a wife’s last wish.

On the landing Maidment arranges towels and sheets in the hot cupboard, placing those not yet aired closer to the cistern. In the bedroom that is to be Mrs. Iveson’s he raises a window sash in order to expel a wasp, satisfies himself that the bulbs of the bedside lamps do not need to be replaced, extracts from the welcoming flowers a sweet-pea whose stem has failed to reach the water in the vase. ‘The Rib, four thirty,’ he keeps his voice low to instruct on the landing telephone. Palm cupped around the mouthpiece, he gives the racecourse details and makes his wager.

Outside, a car door bangs, there’s Rosie’s bark. Not hurrying, for Maidment never does, he makes his way downstairs, to carry up Mrs. Iveson’s suitcases.

The canal doesn’t have any barges on it and only a sludge where there should be water. She discovered the towpath that runs by it the night she stayed late at the door in the wall and there wasn’t a bus to the railway station. No one is about when she passes the broken petrol pump and the shop and the public house.

Seven times in all she has phoned in the weeks that have passed, five times replaced the receiver when it wasn’t his voice. Twice she has put down flowers for him to find, but this afternoon she hurries by the graveyard, not going in to see if he has put fresh flowers down himself. This afternoon she’s anxious to get to the door quickly.

She opens it cautiously, an inch or two, when she arrives, even though she has made friends with the dog. She can hear a movement in the undergrowth, not far from where she is. In a moment, paws scratch and the dog’s nose is pressed through the crack. She can see its tail wagging and she reaches in and pats its head. It goes away then, as it did the other time.

‘They called it the October house,’ she hears after another long wait, his voice reaching her easily.

Sixteen-sided, the summer-house was built to catch the autumn sun, he is telling the old grandmother, who’s dressed all in white. It was positioned with that in mind, he says, its windows angled for that purpose. The dog is with them, panting in the warmth.

‘Well, that’s most interesting,’ the grandmother says, and Pettie can tell that this is what she has been dreading, that this old woman has come to take her place.

‘The Victorians experimented more than people know.’

Some of what is said next is lost, but then they’re nearer and he’s talking about the trees, pointing at them. He refers to the grass of the lawns, saying he remembers a time when it was two feet high. Nettles grew through the heather-beds on the slopes, he says, and thistles in the rose-beds. The grandmother says something about a diary that went on and on, year after year, and he says oh yes, Amelia Davenant’s journal, before his time.

‘Letitia talked about it,’ she says.

‘Letitia liked it.’

It seems it’s history now, this diary, written during some woman’s sleepless nights, yonks ago — entries about a chimney being swept and milk going sour and marmalade made, an Indian selling carpets at the door. A punnet of raspberries, picked and left down somewhere, could not be found. A cousin got engaged. The well didn’t fill, a duchess was murdered in some foreign place. He’s making conversation with all that; doing his best, you can tell from his voice. He doesn’t want what has happened. He doesn’t want this old woman in his house.

‘At parties they used to dance outside. Waltzes lit from the downstairs windows and the front door. Music in the hall.’

‘Yes. Letitia said.’

Some gardener or other came back from the trenches in a shocking state. ‘He showed his wound to the children. Here, among his vegetable-beds. Among them was my father.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death in Summer»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death in Summer» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death in Summer» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.