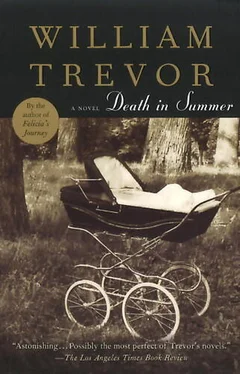

William Trevor - Death in Summer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Death in Summer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death in Summer

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death in Summer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death in Summer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death in Summer — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death in Summer», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The car arrives, and then he’s there. She didn’t know that he was out somewhere. All the time on her journey she imagined him in the sunshine in his garden, and she wonders now where he has been. It could not have been the grave, for she’d have seen the car parked as she passed. Has he gone from shelf to shelf in a supermarket, having to because he has no wife to do it for him now? The dog is with him in the garden, and when he walks back to the house the dog remains.

She edges the door in the wall open, distrustful of the dog, but it doesn’t come. An hour passes, and then the woman dressed in black appears. She picks something that grows close to the ground, a bunch of greenery she goes away with. Soon after that the dog comes to the door and Pettie pushes it closed. She opens it gingerly; the dog just looks at her, wagging its tail. She takes a chance, patting its head, and then it bounds off.

Yesterday, twice, she put the receiver down immediately when it was that woman who answered. But an hour or so later his voice said, ‘Hullo,’ and when she walked away from the phone box she could feel such happiness as she never knew before. On the street two women stared at her and she stared back and laughed, wanting to tell them, wanting to say his name to them.

Trees protect her from the windows, a leafy barrier through which, after another wait, she watches the gaunt man light up a cigarette, far away in the yard. She noticed the green door in the arch of the high brick wall when he allowed her and the other girls to walk in the garden while they were waiting for the interviews. The two who kept together didn’t speak, one and then the other going off when her moment came to ring the doorbell. She being the last, she waited longest and, passing the door in the wall for the second time, she opened it and saw leading from it the path through the fields.

The green paint has blistered and faded on the door. There is an iron casing within the archway that spreads two hinges in a pattern like the outline of a leaf on to the door itself. He has opened and closed this door. How many times? The metal latch is strong, moves easily, its tongue shaped for the thumb that operates it. How often has he touched it? How often does he still? She bends down to caress it with her lips. Her eyes are closed, a cheek pressed hard against the worn green paint.

Dusk comes, the last of the light pale in the sky. Reluctantly Pettie goes away, lingering to look back at the tall chimneys of the house, their brick arranged in decoration that can’t be distinguished now, darkly silhouetted against the sky. On either side of the way through the fields she picks flowers she doesn’t know the names of, and picks more from the verges of the lane. In the graveyard she finds a jam-pot on a neglected grave and fills it with water from a tap by the side of the church. Her flowers are colourful in the gloom, beside the withering blooms on the mound of fresh clay. She leaves them there for him to find, to comfort him in his grieving.

5

‘Well, good days, bad days,’ the nurse at St. Bee’s reports on the telephone, no tiredness in her tone, no hint of the tedium of having again to say what she has said so often before. There is a cheerfulness even, and Mrs. Iveson recalls the slapdash features of the woman’s face in which, as if to establish some kind of order, eyebrows are plucked and lips given a well-defined outline. She recalls the starched white uniform, the rinsed hair beneath the starched white cap, the watch pinned to a flattened bosom. When it was agreed that she should move to Quincunx House she rang St. Bee’s and explained to this same nurse about the change there was to be in her life and what had brought it about. ‘Oh, my God!’ the woman exclaimed then, her shock faltering into distress, sympathy offered when she recovered.

‘You’re settling in, Mrs. Iveson?’ she says now, three weeks after the arrangement was agreed, a fortnight after Thaddeus’s rendezvous with Mrs. Ferry.

Later today.’ A telephone number is given, repeated in St. Bee’s.

‘It’s marvellous ofyou, Mrs. Iveson. It’s simply marvellous.’

‘Not really.’

‘Indeed it is. Not that I don’t envy you, an infant that age. Day to day, there’s something new.’

‘I suppose there is.’

It isn’t true, but of course it doesn’t matter. Chat there has to be. Well, at least she has her grandchild, they would have commented at St. Bee’s when news of the death was earlier passed on. ‘And to think he doesn’t know!’ would have been said, as so often it must be in this home. Georgina was called after him, he being a George, but he doesn’t know that either.

‘A joy at that age, I always say, not that it takes an iota away from the gesture you’re making, Mrs. Iveson. We’re all full of admiration, we really are.’

She isn’t young, they would have said; it’s not as though she’s young. Moving right in like that, not faltering or going to pieces, turning her back on what she knows, not that change isn’t the best tonic when there’s been what there has been. And of course it’s natural, a daughter’s baby.

‘Never hesitate to call us up, dear. Don’t ever think it’s a nuisance, ringing up. In circumstances like this, I always say it’s good to talk.’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, I have the details, dear. Thanks ever so.’

Both receivers are replaced in the same moment. Who says lightning doesn’t strike twice? would have been said in St. Bee’s over cups of tea, the subject kept alive to ease the monotony of the day. No more’n a vegetable in tweeds, and now all this, the kiddy needing a mother’s hand, fortunate the father’s in agreement, unusual that.

I can’t say I’m not nervous about this upheaval, Mrs. Iveson last night finished a letter to her longtime friend in Sussex, and perhaps this is not at all what Letitia would want. Well, if it doesn’t work it doesn’t. We can only try.

She has let her flat to people called Redinger from Oregon, who say they like a good address. She chose them because something about their manner suggested to her that they would be careful tenants. Their tenancy is for four months only, since that is the period of their stay in England; and when it finishes the agency will come up with other people, whom she can also personally vet if she wishes to continue to let the flat. She could less inconveniently have left it empty, visiting it herself from time to time to see that all was well. But the advice she has received is that empty property, these days, attracts burglary: the Redingers and any successors they may have would be caretakers as much as tenants. With that in mind, and against the wishes of the agency she employed, she has asked for only a modest rent.

Often during the days that passed while all this was so swiftly arranged, Mrs. Iveson has experienced the doubts she expressed in her letter to her friend, but on each occasion has successfully wrangled with her misgivings. Within the tenancy agreement there is also a clause, specifically at the Redingers’ request, that allows one month’s notice on either side, should there be a change of circumstances. This is a comfort.

It is particularly so when Mrs. Iveson looks through what remains in cupboards and drawers on the morning of her departure, as she unlocks and locks again the built-in wardrobe that contains the clothes she isn’t taking with her. Everything is in order in the kitchen, the refrigerator empty, the electric kettle unplugged. The News comes unobtrusively from her Roberts radio, the sound turned down. Earthquakes in Russia, riots in Hong Kong, a body on a river path in Wales, carnage in Croatia. And five hundred pounds to be paid as compensation to a canary breeder who declares himself devastated after a single measure of seed swelled to ten times its bulk in his prize bird’s stomach, destroying all chance of success at the Culross and Kincardine Cage-birds Festival.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death in Summer»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death in Summer» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death in Summer» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.