So I must say to you that our pressure must be sustained—and will be sustained—until he realizes that the war he started is costing him more than he can ever gain.7

Johnson’s surmise that the North Vietnamese leadership believed they could outwait the United States government was well justified. After all, if the North Vietnamese followed American public opinion polls, as they surely did, then they knew, as we saw in Figure 5.1, that American support for the war was collapsing. At the time of his 1967 State of the Union Address, just shy of 50 percent of Americans judged the war to have been a mistake. By the summer of 1968, eighteen months after his 1967 State of the Union Address, a majority of Americans considered the Vietnam War a mistake. Seeing the handwriting on the wall, on March 31, 1968, Johnson, still unable to see the path to a US victory in Vietnam, announced, “I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President.”8 The North Vietnamese may well have interpreted this statement as meaning, with justification, that the war was costing Johnson “more than he can ever gain.”

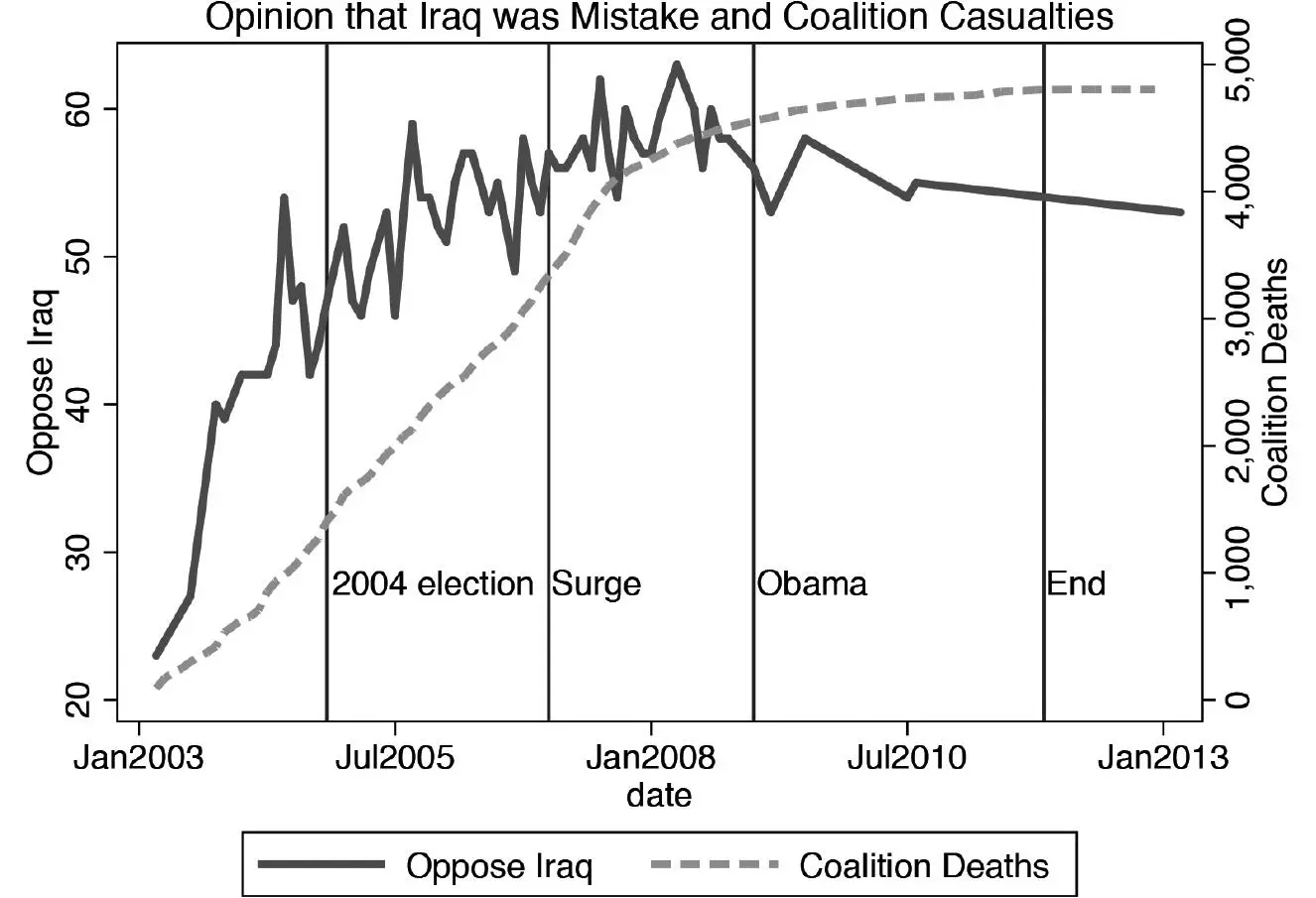

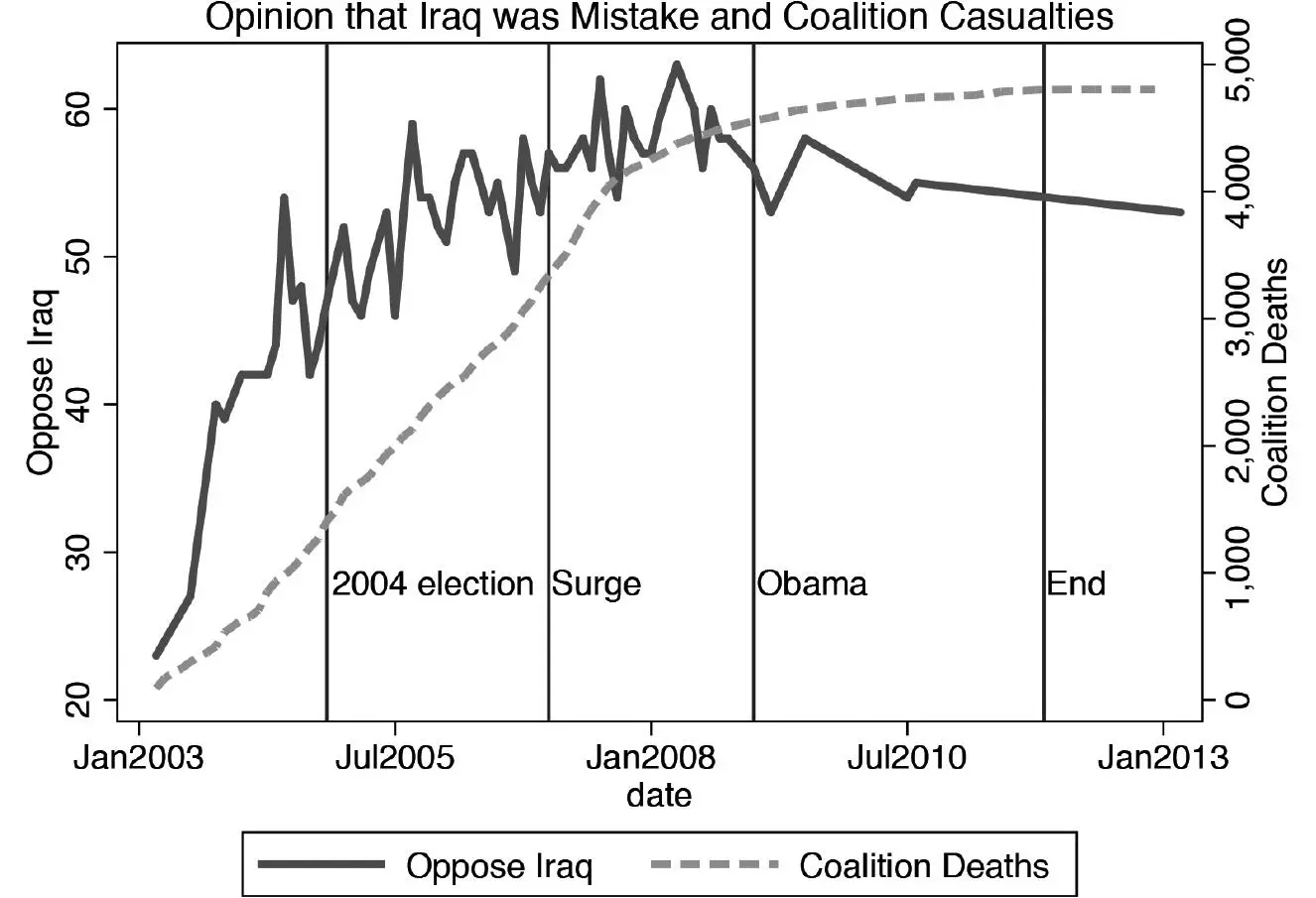

Figure 5.2 shows public opinion of the war in Iraq in 2003. It is largely a reprisal of the story of Vietnam, with one huge difference. It shows, as Figure 5.1 does regarding Vietnam, that American public opinion about the Iraq War of 2003 and its aftermath strongly tracked the US casualty rate. That rate, of course, was an order of magnitude lower than in Vietnam, yet that difference does not seem to be the explanation for Bush’s political success and Johnson’s failure. As Johnson failed to defeat the Vietnamese, Bush failed to secure the peace in Iraq. Overrunning the Iraqi military proved easy enough as these things go, but the Bush administration seemed unprepared to turn military success into effective postcombat governance. Instead, open warfare against Saddam Hussein’s regime ended quickly, only to be replaced by insurgency verging on civil war. Whereas it took three years for a majority of the American public to turn against Johnson’s war, it took barely a year, albeit with many rises and declines in support, for Bush to experience for the first time—and not the last—the same loss of support. Johnson was unable to reverse the trend against his war; Bush managed to engineer a saw-toothed pattern of rises and declines in support, and got himself reelected during a period of relative popularity, even though the war was later seen as a failure. That, of course, leaves us with big questions: What did Bush do right politically; what did Johnson do wrong; and how can lessons from their experiences be used to reduce the danger of needlessly engaging in costly wars? The answers are not hard to find, although they may be hard to digest.

Figure 5.2. Coalition Casualties in Iraq

Sources: http://icasualties.org/IRAQ/index.aspx, http://www.gallup.com/poll/1633/iraq.aspx

LBJ: A Reluctant Warrior

THE LINES IN THE SAND HAD LONG BEEN DRAWN IN SOUTHEAST ASIA when LBJ became president. To be sure, it was he, not Eisenhower and not Kennedy, who sought and secured the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and, likewise, it was he, not Eisenhower or Kennedy, who first openly committed American combat troops to the mission of defeating South Vietnam’s North Vietnamese and Viet Cong adversaries. But that was against a backdrop of long-established views that relentlessly pushed President Johnson toward intervention and toward incremental but massive escalation in Vietnam.

Intervention not only followed the consensus opinion regarding Vietnam at the time; it was also consistent with the principal goal of US policy since the end of World War II: to contain communism. Involvement in Vietnam was a gradual process in which Johnson sought and listened to differing opinions. In hindsight, many judge US involvement in Vietnam to have been a tragic mistake. The United States spilled much American and Vietnamese blood and treasure and still, in the end, South Vietnam was lost. But it is unfair to judge decision making from the perspective of a Monday morning quarterback. The appropriate standard for evaluating decisions is whether the right choice—that is, a reasonable, well-considered, justifiable choice—was made given the information available at the time. This is precisely the analysis that Leslie Gelb and Richard Betts undertook in a 1979 book for the Brookings Institution, the title of which conveys their central argument: The Irony of Vietnam: The System Worked . They argued that “the paradox is that the foreign policy failed, but the domestic decision-making system worked.”9 In particular, the system worked because “(1) the core consensual goal of postwar foreign policy (containment of communism) was pursued consistently; (2) differences of both elite and mass opinion were accommodated by compromise and policy never strayed very far from the center of opinion both within and outside the government; and (3) virtually all views and recommendations were considered and virtually all important decisions were made without illusion about the odds for success.”10

So, putting hindsight aside, what were the competing arguments that Johnson heard and weighed at the time he had to choose his course of action? Advice from senior members of his foreign policy team ranged across the entire spectrum from those in favor of escalation to those in favor of withdrawal. To stress the openness of the internal discussion at the time, consider the account Johnson’s special assistant, Jack Valenti, provided of Cabinet Room debates that started on July 21, 1965, and continued until LBJ’s announcement of substantial escalation on July 28. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara had just returned from Vietnam. His memorandum proposed a massive increase in US forces, without which he predicted South Vietnam would be overrun by the communists. Johnson, as Valenti tells it, was far from gung-ho for war. He pushed George Ball, undersecretary of state, to express his reservations. Ball answered, “Mr. President, I have grave misgivings about our ability to win under these conditions. . . . But let me be clear. If the decision is to go ahead, I will support it. . . . There is no course that will allow us to avoid losses. But if we get bogged down, our cost might be substantially greater. The pressures to create a larger war would be irresistible. . . . We can take our losses and let their government fall apart, Mr. President, knowing full well there will be a probable takeover by the Communists. This is an unpleasant alternative, I know.” LBJ responded, “I don’t think we have made any full commitment yet, George . . . I want another meeting, more meetings, before we take any definitive action. We must look at all other courses of action carefully. Right now I feel it would be more dangerous to lose the war than it would be to risk a greater number of troops down the road. But I want this fully aired.”11

Later in the discussion, Ball prophetically reveals his reservations: “We cannot win, Mr. President. This war will be long and protracted. The most we can hope for is a messy conclusion. . . . I think a long, protracted war will expose our weakness, not our strength. The least harmful way to cut losses in South Vietnam is to let the government decide it doesn’t want us to stay there. Therefore we should put proposals to them that they can’t accept, although I have no illusions that after we are asked to leave South Vietnam, that country will soon fall under Hanoi’s control.”12

While Ball feared that the United States would be bogged down without winning, others expressed support for expansion. For instance, General McConnell said, “If you put in these requested forces and increase air and sea effort, we can at least turn the tide to where we are not losing anymore. We need to be sure we get the best we can out of the South Vietnamese. We need to bomb all military targets available to us in North Vietnam. As to whether we can come to a satisfactory solution with these forces, I don’t know. With these forces properly employed, and cutting off the VC supplies, we can surely do better than we are doing now.”13

Читать дальше