Two Wars: Superficial Similarities, Fundamental Differences

THE BATTLEFIELD EXPERIENCE AND THE POLITICAL FALLOUT FROM BOTH the Vietnam War and the Iraq War are similar. In each instance, things mostly went well in combat and yet turned sour when it came to politics, though in the case of Iraq, the sourness did not set in until after Bush was reelected, whereas Vietnam deprived Johnson of a second term. The United States was militarily dominant in classic battle terms between regular army units in both Vietnam—mostly a war of set-piece battles, despite its reputation—and in Iraq. Despite military success against regular army units, in both cases US forces proved vulnerable to unconventional warfare and US military commanders struggled against enemies who could not be readily brought to the negotiating table and who could not be effectively controlled following settlement of each conflict.

Eventually, the American public tired of both conflicts, producing disastrous political results for Johnson but, curiously, not for Bush. Explaining why that was so is the central theme in this chapter. In resolving why Vietnam destroyed Johnson while Iraq did not destroy Bush, we will hear an echo of James Madison’s War of 1812. Making partisan adversaries bear the cost of war, as the Democrat-Republicans did in 1812 and as Bush did in 2003, is great for reelection prospects and awful for the unity and well-being of the country. Conversely, a pay-as-you-go, debit-card plan to cover the costs of war while it is being fought helps secure the country’s economic and social future, but at a heavy personal price for presidents who choose that course of action. Johnson was ruined by his war payment scheme. This ruination was caused by his use of taxation to cover the financial burden of war and of an equal-risk scheme to populate the military. Bush, in contrast, was made by his war payment scheme!

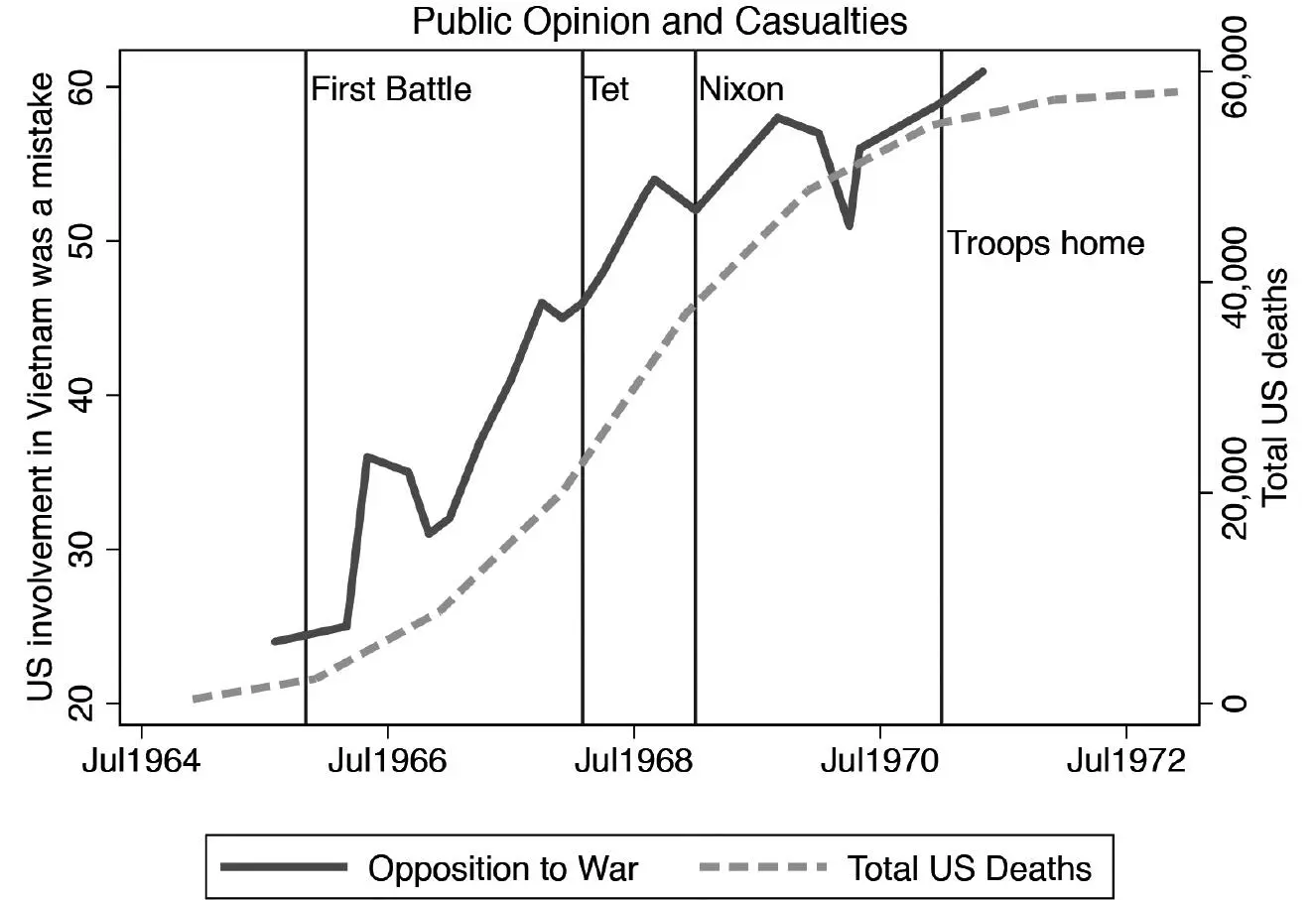

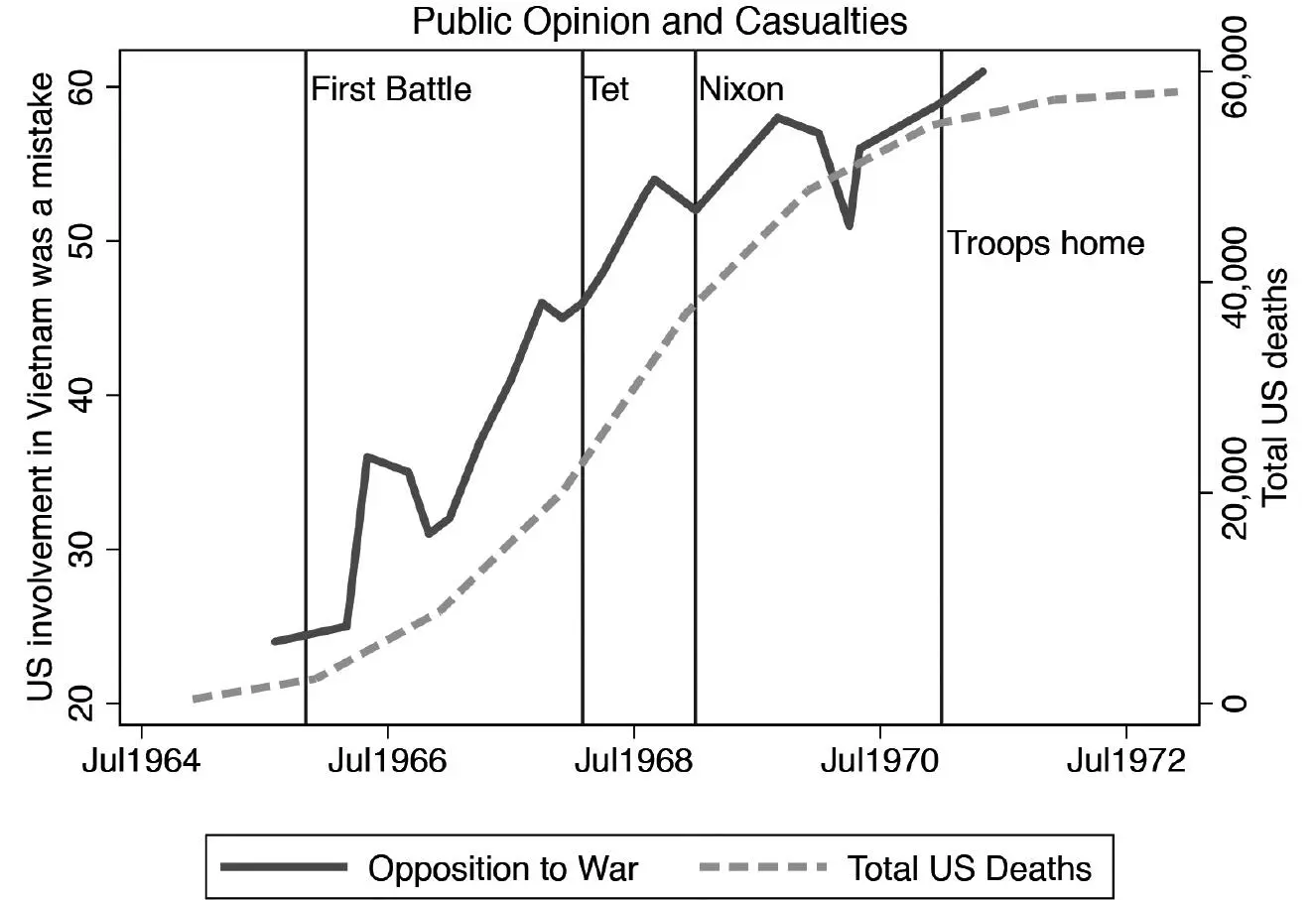

We begin with a review of public opinion polls for each war. Figure 5.1 shows the percentage of Americans who thought that US intervention in Vietnam was a mistake (solid line), according to Gallup polls from the summer of 1964 through the election of Richard Nixon.2 We quite intentionally start in the summer of 1964. On August 2, 1964, the USS Maddox reported being attacked by three North Vietnamese torpedo boats in the Tonkin Gulf. A second alleged incident occurred two days later. We say “alleged” because serious doubts have been raised over whether the reported events actually happened, at least as publicly described. In any event, Congress believed the attacks occurred as reported and responded with the Tonkin Gulf Resolution. The resolution authorized the “President, as Commander in Chief, to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.” It went on to note that “the United States is, therefore, prepared, as the President determines, to take all necessary steps, including the use of armed force, to assist any member or protocol state of the Southeast Asia Collective Defense.”3 This resolution passed against only two nay votes, by Democratic senators Wayne Morse of Oregon and Ernest Gruening of Alaska. Thus, the summer of 1964 may be seen as marking the start of Lyndon Johnson’s phase of the Vietnam War and hence as a sensible place for us to begin to evaluate how public views of the war unfolded and what that unfolding meant for him.

Figure 5.1’s right vertical axis and the dotted line show the cumulative number of US casualties during the Vietnam War. The solid line, linked to the left vertical axis, displays the percentage of the American public that assessed the war as a mistake between July 1964 and the fall of 1972.4 We can see clearly that the American public initially was firmly behind Johnson’s decision to intervene following the Gulf of Tonkin incident and subsequent congressional resolution. Less than a quarter of the population opposed Johnson’s first serious Vietnam engagement in 1965. However, as US casualties mounted, opposition to the war increased. Declining public support and rising casualties track each other closely throughout the war.

Figure 5.1. US Public Opinion and Casualties in the Vietnam War

Sources: http://www.gallup.com/poll/2299/americans-look-back-vietnam-war.aspx, https://www.dmdc.osd.mil/dcas/pages/report_oif_month.xhtml

Looking at the vertical line in Figure 5.1 that denotes the North Vietnamese’s Tet Offensive, it is interesting to recall that Tet resulted both in a decisive US military victory and in just as decisive a US political defeat. Although initially the US military was shocked and stunned, perhaps having believed its own propaganda about the weakened condition of the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong (VC), US forces quickly organized and counterattacked. They killed around 37,000 Viet Cong soldiers compared to 2,500 US losses. The Tet Offensive seriously depleted North Vietnam’s military capacity but it produced a stunning North Vietnamese political victory as American public opinion turned more sharply against the war. CBS’s news anchor, Walter Cronkite, often described as “the most trusted man in America,” reported, “To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe, in the face of the evidence, the optimists who have been wrong in the past. To suggest we are on the edge of defeat is to yield to unreasonable pessimism. To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, yet unsatisfactory, conclusion.” Johnson understood the significance of Cronkite’s assessment. He retorted, “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost Middle America.”5 That is, he lost a big chunk of his personal base of political power.

Johnson had indeed lost Cronkite and America. US government declarations by the president, his foreign policy team, and senior generals had led the public to believe that the North Vietnamese no longer were capable of mounting an offensive. Following Tet, opposition to the war rose sharply, surpassing 50 percent for the first time, as a credibility gap expanded between what the president was saying and what the American people believed.

From early on in his presidency, Johnson’s official pronouncements came increasingly to be seen as inconsistent with the media’s reports out of Vietnam. He had chosen to follow the modus operandi that he had perfected in the Senate, maneuvering to create the impression of a happier vision of reality than the facts on the ground warranted. As Johnson’s special assistant, Joseph Califano, stated, “At his worst, Lyndon Johnson destroyed his own credibility. He hid the true cost of the military buildup in Vietnam as he first unfolded it. He heard what he wanted and hoped to hear from the military about the war and passed their optimistic reports on to the American people as his own. . . . He learned too late that the manipulative and devious behavior commonplace in the back alleys of legislative politics appalled the American people when exposed in their President. He paid a fearful price as first the press corps in Washington and Saigon and then millions of Americans came to doubt his word. He never seemed able to accept what the war did to the American spirit.”6

As the war effort escalated with ever growing numbers of American troops in Vietnam, Johnson recognized that optimistic reporting combined with a prolonged war had the potential to create devastating political consequences. Even a year before the Tet Offensive, in his 1967 State of the Union Address, he admitted that the end was not yet in sight:

I wish I could report to you that the conflict is almost over. This I cannot do. We face more cost, more loss, and more agony. For the end is not yet. I cannot promise you that it will come this year—or come next year. Our adversary still believes, I think, tonight, that he can go on fighting longer than we can, and longer than we and our allies will be prepared to stand up and resist. . . .

Читать дальше