[W]e must honestly face our relation-ship with Great Britain. We must admit that the loss of the British Fleet would greatly weaken our defense. This is because the British Fleet has for years controlled the Atlantic, leaving us free to concentrate in the Pacific. If the British Fleet were lost or captured, the Atlantic might be dominated by Germany, a power hostile to our way of life, controlling in that event most of the ships and shipbuilding facilities of Europe. This would be a calamity for us. We might be exposed to attack on the Atlantic. Our defense would be weakened until we could build a navy and air force strong enough to defend both coasts. Also, our foreign trade would be profoundly affected. That trade is vital to our prosperity. But if we had to trade with a Europe dominated by the present German trade policies, we might have to change our methods to some totalitarian form. This is a prospect that any lover of democracy must view with consternation. The objective of America is in the opposite direction. We must, in the long run, rebuild a world in which we can live and move and do business in the democratic way.16

Willkie’s fear of calamity reflected the reality of the changed map of Europe as of June 1940. FDR’s call for expanding the national defense may well have had the same rhetorical purpose. Unlike Willkie, who could afford campaign hyperbole, Roosevelt was president and commander in chief. In those capacities he had to come to a sober judgment of the right course for America. Popular sentiment was for staying out of Europe’s affairs. The president was responding to that sentiment even as he seemed to recognize that this was a dangerous course to follow. When confronted with choosing between the possibility of electoral setbacks if he followed an aggressive foreign policy and the threat of the loss of practically the final surviving democracy in Europe—Great Britain—he elected to gamble on the latter course.

While the president spoke of the need for an expanded national defense—and indeed the country surely did need it—the facts showed that he had not prepared the nation for the vigorous defense it potentially needed. Expanding national defense meant more job opportunities, enhancing economic recovery, and more national security against the growing threat from Germany and Japan. However, he was pursuing a minimalist rearmament strategy in his alleged commitment to expand national defense and military preparedness. As late as September 1940, the US army was only eighteenth in the world in size, smaller than the armies of the nation’s potential adversaries Germany and Japan; smaller than its prospective allies England and France, before the latter’s fall; and even smaller than the armies of Belgium, Holland, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland. To be sure, Roosevelt responded to urgings from Charles Lindbergh and William Bullitt (US ambassador to France) to expand US air power. They had independently noted that Germany had air superiority relative to everyone in Europe, and that the French and the British needed to rely on American airplane production to resist the Germans.17 The expansion that was undertaken could be seen as proportionately large, but then it is easy to achieve high growth when the baseline starting position was near-zero military aircraft. Thus, in 1940, during the presidential campaign and before his nation’s entry into the war, the US military had 3,807 airplanes compared to 19,433 in 1941 and 47,836 in 1942, when the United States was in the war.18

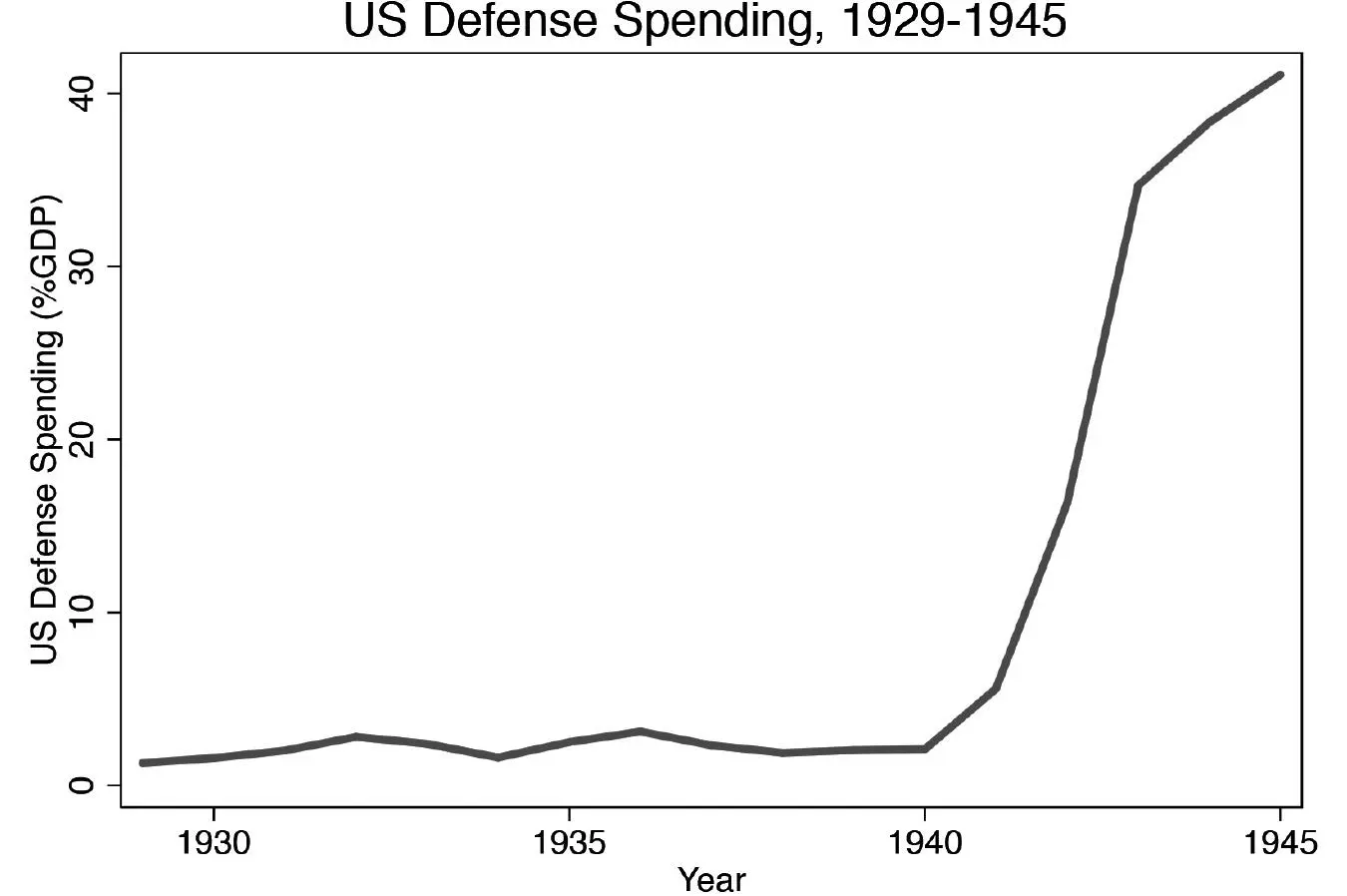

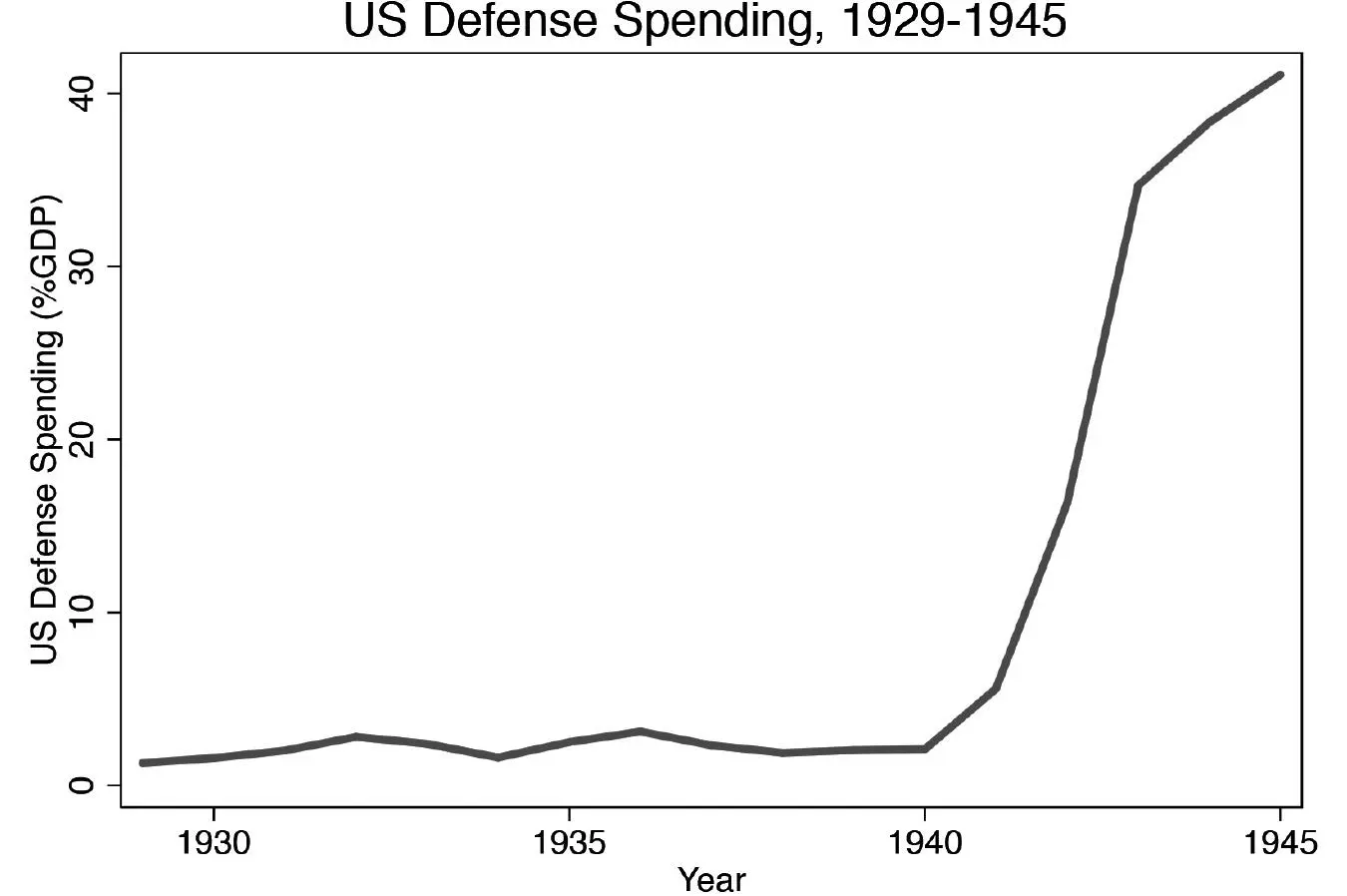

Despite FDRs declaration on behalf of expanding America’s defense capability, the actual expansion was rather modest, given the world situation. Consider the facts depicted in Figure 4.2. This figure shows US military spending as a percentage of gross domestic product for the years from 1929—the beginning of the Depression—through 1945. Roosevelt told the Democratic Party faithful in his July 19 speech that only the blind or the partisan could fail to recognize as of the spring of 1939 that war was nearly inevitable and that “such a war would of necessity deeply affect the future of this nation.” Yet looking at the figure, we are hard-pressed to see evidence of a serious effort to prepare for the defense of the nation before the United States entered the war at the end of 1941. Indeed, defense as a portion of the national economy slightly declined between 1936 and 1940.

The president’s acceptance speech spoke of preserving democratic governments against the attack by dictatorship; that is, by the unnamed Nazi Germany. Here again he substituted rhetoric for action, even as the calamity in Europe pulled the noose ever tighter. While he declared that it was America’s duty “to sustain by all legal means those governments threatened by other governments which had rejected the principles of democracy,” at the time of the speech there was barely any surviving democracy in Europe. Britain was alone in sustaining the fight against Hitler west of the Soviet Union. Where was Roosevelt’s decisive action to go with his bold words? It was not to be found.

Figure 4.2. US Defense Spending as a Percentage of GDP, 1929–1945

Source: http://www.usgovernmentspending.com/defense_spending

Roosevelt was certainly not blind to what was happening—to what, in fact, had happened—in Europe. He was, however, a candidate for office and, as such, naturally partisan. Especially in the face of calamitous times, leaders are expected to lead. If their constituents have not yet understood the necessities of the moment, it is the leader’s job to educate them to the threat they face. Wendell Willkie, for his own partisan purposes, tried to do just that when he accepted his party’s nomination. He did not mince words. He explained why the defeat of Britain would be a calamity for the military and economic security of the United States. President Roosevelt was more reserved. It seems he chose to follow voter opinion rather than to sway that opinion. For example, consider the series of Gallup polls conducted during 1940.19

The Gallup survey conducted during the first week of February 1940, asked, “Do you think the United States will go into the war in Europe, or do you think we will stay out of the war?” Of those responding, 68 percent indicated the United States would stay out, a sentiment that the president echoed regularly. The same poll also inquired, “If it appears that Germany is defeating England and France, should the United States declare war on Germany and send our army and navy to Europe to fight?” The response: 77 percent said no! The numbers are all the more depressing when one realizes that when asked which side they favored (March 8–13, 1940), 84 percent of respondents said they wanted to see England and France prevail but they were not prepared to help make that happen. Asked, “Should we declare war on Germany and send our armed forces abroad to fight?” at the end of March and beginning of April, 96 percent responded no!

What politician, facing such overwhelming public opinion, would dare to reeducate the population that its view was “blind” to the facts on the ground? Well, we know that Franklin Roosevelt was not to be counted among any such profile in courage. The man who courageously had led America to embrace the New Deal, which represented a radical departure from standard economic thinking at the time, was nowhere to be found in 1940. He was not reeducating the American people; he was following their lead. He had not taken the opportunity presented by Germany’s invasion of Poland to redirect American thinking. At that time, the more distant, less headline-grabbing conflict in Asia was not foremost in American minds. In the Pacific theater, the president imposed embargoes and took a tougher line, but that was less likely to harm his reelection than taking bold steps to challenge Hitler.

Читать дальше