The First Roosevelt: 1932–1940

BEFORE CONSIDERING OUR MAIN THEME—FDR’S VANITY AND URGE FOR power at the expense of decisive leadership—we pause to set the stage by recalling the Roosevelt who led from 1933 until the 1940 election. That Roosevelt came to office with the Depression in full swing. His hands were certainly full. He was confronted with no less than having to find a way to utterly reconstruct the American economy, the national standard of living, and the American way of life. He faced an uphill battle and he knew it. One of the great strengths he brought to his new job was his indomitable commitment to find a way through the morass and rescue the American people. Roosevelt certainly understood that he was not an economist; he was not a successful entrepreneur; he was not the common working man—the forgotten man—or a homemaker wondering where the children’s next meal would come from; he was not a philosopher; and he was not a magician. He was a politician with the practical bent of a success-oriented competitor for high office. He had no illusion that he knew the solution to the country’s economic woes. Nor did he have any illusion that economists or anyone else had squarely worked out the logic of macroeconomics and, therefore, knew how to fix the terribly broken economy.

What he knew or, at least, what he believed he knew, was that a solution waited to be discovered and, further, that he knew the means to discover it. As he said in his speech at Oglethorpe University in May 1932, “The country needs and, unless I mistake its temper, the country demands bold, persistent experimentation. It is common sense to take a method and try it: If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.”5 And try something, and then something else, is just what he did. He had no roadmap to lead the way to economic recovery, but neither did he fear to go down untrodden paths, bringing the people along with him. He knew no fear. He did not retreat from his vision when others accused him of socialism or dictatorship. Rather, he pressed forward boldly, looking for a way to make true his declaration that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

Roosevelt inspirationally argued that it was prudent to roll the dice, run social experiments, and see what might salvage the people of the United States. He earned enormous popularity—and not a little hostility—for his frank willingness to gamble on new solutions. His New Deal inspired many by the boldness of its vision and its contents. Departing from the laissez-faire economics that had been the engine of investment, entrepreneurship, and enormous economic growth in America’s first century and a half, Roosevelt recast the country’s predominant economic philosophy as a philosophy that had produced great inequalities in opportunity and in outcomes. In redirecting economic thought and redefining social goals, Roosevelt made himself into the beloved champion of the ordinary, forgotten American rather than the extraordinary American. He gave the United States a social safety net, a much bigger government than it had ever had, higher taxes, entitlements, and a sense of a more equitable distribution of chances to realize the American dream. Although it took a world war to rescue the US economy, it was Roosevelt’s bold experimental approach that persuaded people to get to work making the recovery last. He led with ideas, correctly confident that the average American would follow him where he wanted to go.

How important the Second World War was to the reestablishment of economic growth and hope has been the subject of vast amounts of debate over the causes and solutions to the Great Depression. These accounts, regardless of their perspective on whether Roosevelt deserves great credit for alleviating the effects of the Depression or whether he is to be faulted for slowing progress to recovery, are not our concern. In this chapter we want to understand how Franklin Roosevelt, the mythological, heroic leader through the long, dark years of World War II, made the war longer, more dangerous, and costlier than it needed to be. We contend that he did so to advance his personal vanity, presenting himself to the American people as their indispensable leader in times of crisis. Our critique of Roosevelt, despite being backed by substantial evidence, is in an important regard surprising even to us. His prewar procrastination, dithering, and dissimulation all served his electoral ambitions but, we believe (with the benefit of hindsight), not nearly as well as they might have been served had he made bolder decisions to enter the war in Europe along with Britain, France, and numerous Commonwealth nations, joining before Germany was given the time to create a massive calamity. The inventive Franklin Roosevelt of 1933 was much better suited to the challenges faced in 1939–1945 than the Johnny-Come-Lately Roosevelt who refused to lead.

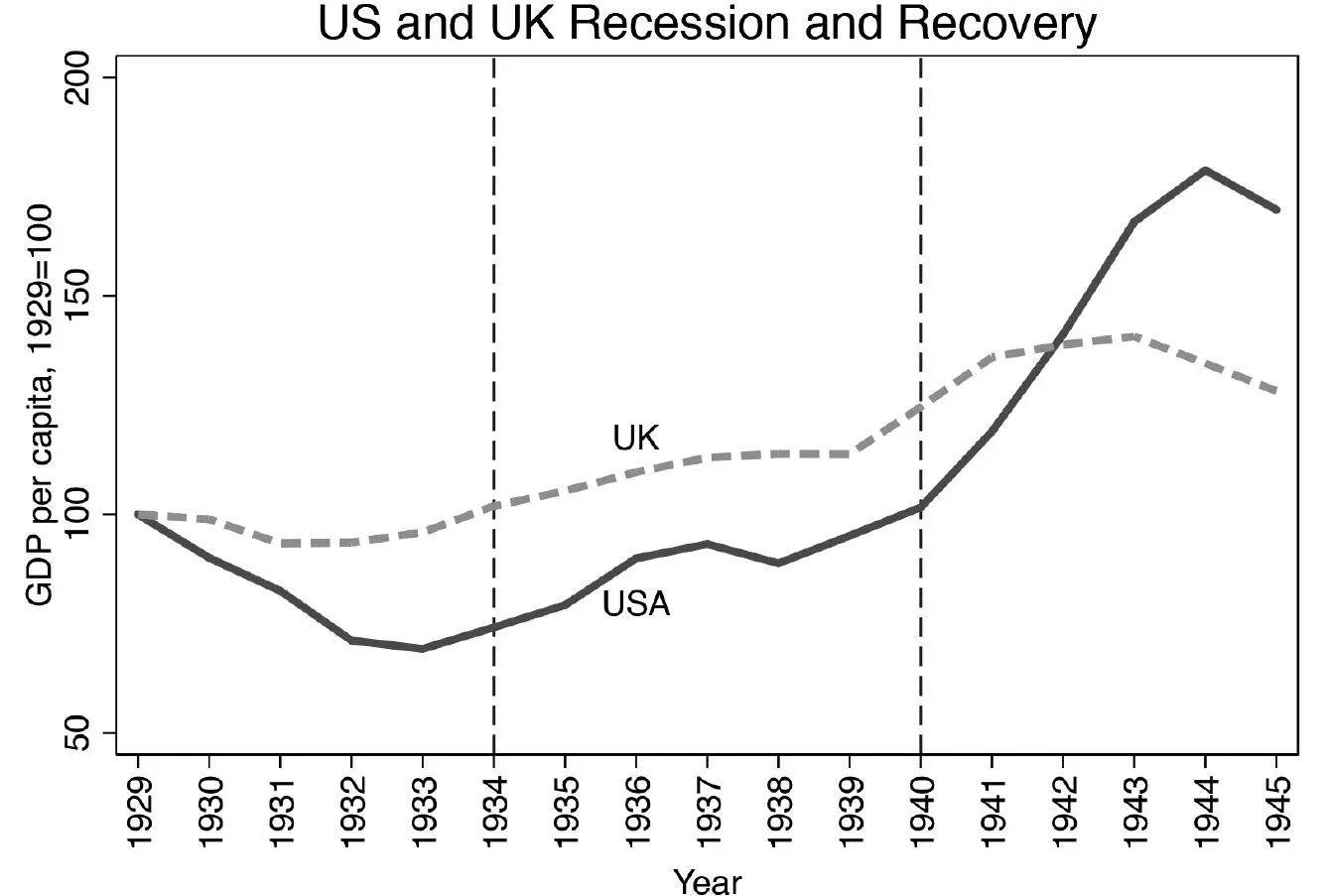

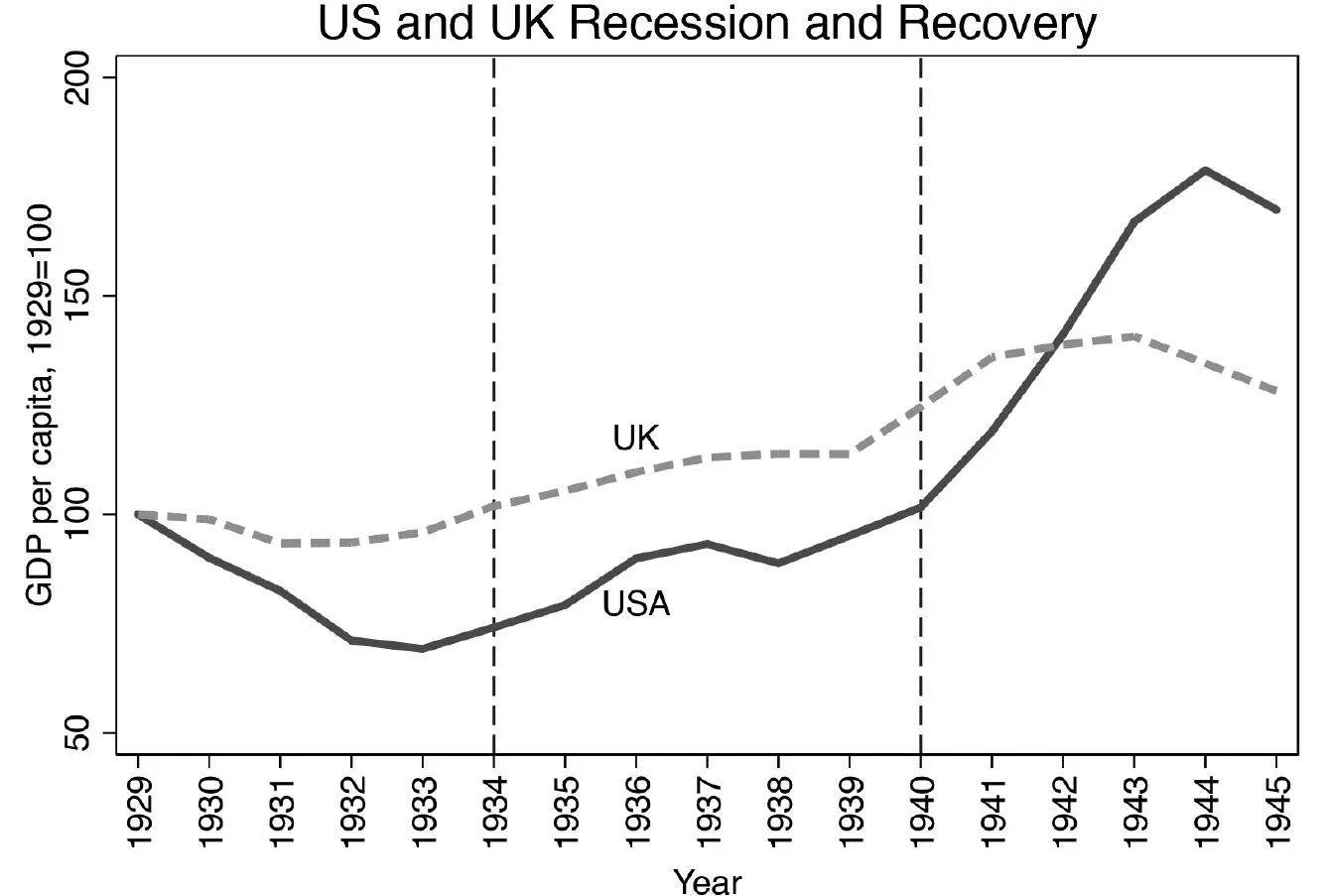

Consider Figure 4.1, which compares the US and British gross domestic products (GDP) to each other from 1929 (that is, the beginning of the Depression) through 1945, marking the end of the Second World War.6 Here we can begin to see a bit about the difference between the Roosevelt elected in 1932 and 1936 and the Roosevelt reelected again in 1940 (and 1944).

Figure 4.1. Economic Recovery and the War

Source: https://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/media_nm.php?ModuleId=10005453&MediaId=2063

The two economies are “normalized” in the graph so that each begins with a base value of 100 in 1929. Britain, without the New Deal programs but with a continuing ability to engage in international trade, declines economically only slightly in the first few years of the worldwide Depression, returning to its 1929 baseline gross domestic product by about 1933, coincidentally the year Roosevelt became president. Herbert Hoover’s approach to the severe economic contraction, in contrast, seems utterly to have failed. With trade snuffed out by the Smoot-Hawley tariffs, the US economy, unlike Britain’s, had lost its global reach. As the graph shows, the US GDP was only a little better than half of what it had been in 1929 by the time Roosevelt took the oath of office (denoted by the left-hand vertical dotted line).

Having hit its bottom, the economy began to recover slowly following Roosevelt’s inauguration. For those who thought Roosevelt’s policies were wrong-headed, the New Deal ideas were the road to disaster, slowing rather than hastening economic recovery. Wendell Willkie, the Republican nominee for president in 1940—and himself a former backer of FDR’s—decried the New Deal in the speech in which he accepted his party’s presidential nomination in August 1940. His critique encapsulates the general critique of the minority who opposed Roosevelt at the time. As Willkie said,

For the first time in our history, American industry has remained stationary for a decade. It offers no more jobs today than it did ten years ago—and there are 6,000,000 more persons seeking jobs. As a nation of producers we have become stagnant. Much of our industrial machinery is obsolete. And the national standard of living has declined. It is a statement of fact, and no longer a political accusation, that the New Deal has failed in its program of economic rehabilitation. . . . To accomplish these results, the present administration has spent sixty billion dollars. And I say there must be something wrong with a theory of government or a theory of economics, by which, after the expenditure of such a fantastic sum, we have less opportunity than we had before.7

The same data that Willkie saw as all negative can, of course, also be interpreted as showing the success of the New Deal. Returning to Figure 4.1, we see that the GDP was rising after FDR took office, lending support to those who point to Roosevelt’s vision as having revived the economy. Growth had resumed under the New Deal, but despite his many economic and social experiments, the US economy did not grow enough to return to its pre-Depression baseline level until the end of 1940 or the beginning of 1941. That was when, after most of continental Europe had fallen to the Nazis, Roosevelt finally initiated the wartime economic stimulus of the Lend-Lease Act (in March 1941) that opened American factories to massive arms production. We will, of course, have more to say about that. For now, it is useful to consider what might have happened had he geared up to defend Europe earlier. Had he launched the arsenal for democracy in, say, 1939, after the German invasion of Poland, or even earlier, say, after Germany’s remilitarization of the Rhineland in 1936 overthrew key principles of the Versailles Treaty, instead of in late December 1940, war production might have proven the great job creator that it later became. With this surge in US ordnance, Hitler’s threat to the world might have been nipped in the bud, to the benefit of millions who suffered under Nazi occupation and rule. Once Roosevelt finally got around to arming what was left of those fighting Nazi Germany in Europe, the US economy really took off. We see this quite clearly by looking at the graph to the right of the second vertical dotted line. Thus, Figure 4.1 suggests, with hindsight, what the right economic, as well as military, strategy was, given the situation in the world.

Читать дальше