Such an action would have mollified the more reluctant rebels among the founding fathers (perhaps including George Washington), providing a means to protect their investment interests by spreading any tax for the defense of the colonies among all of the British represented in Parliament, rather than by concentrating the burden on the colonists, isolating the more radical colonial leaders. George III might have averted the war while such men as George Washington could have been satisfied that they had a say in protecting their investments from arbitrary rule by Parliament and the king. As Smith stated, “[The colonists’] representatives in parliament, of which the number ought from the first to be considerable, would easily be able to protect them from all oppression. The distance could not much weaken the dependency of the representative upon the constituent . . . It would be the interest of the former [representative], therefore, to cultivate that good will by complaining, with all the authority of a member of the legislature, of every outrage which any civil or military officer might be guilty of in those remote parts of the empire.”31 With the representation that they had said was not possible because of their “peculiar circumstances” having being granted, they would have been in a strong enough position to forge coalitions, making themselves pivotal in significant governmental matters. Doing so would have allowed the American colonial leaders to create political checks against a rapacious desire among others to limit the colonists’ land acquisition and to protect their sources of revenue. Since the king by this time tended to defer to Parliament and Parliament was already divided over how to deal with the colonies, it is not difficult to imagine that by the simple expedient of representation proportional to population the king’s interests and the interests of many founding fathers could have been satisfied. Too bad none had the patience to construct such a simple solution.

Had the colonists been given proper representation in Parliament, we might not have had the American Revolution or, at least, not in the 1770s. What might that have meant for the future? Parliament banned slave trade in 1807 and passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833, which made slavery illegal throughout almost all of the British Empire.32 If the American colonies were then an integral part of Britain, slavery would have been abolished nearly thirty years before the Civil war. Perhaps the southern “parliamentary districts” would have rebelled, but then they would not only have had the northern “parliamentary districts” in America, including the Canadian colonies, against them; they would have had the British Empire opposed to them. Civil war would have been that much less attractive an option and so, perhaps, just perhaps, slavery would have been eliminated earlier and in a less wrenching way than was the case in the 1860s. Against that, remaining part of Britain—but with full representation—would have meant that the US Constitution as we know it, especially its explicit Bill of Rights and its detailed institutions to ensure separation of powers, would not have existed. Rather, the colonies that became the United States might have looked more like the Canadian colonies that secured independence nearly a century after the American Revolution. What that might have meant is the domain of speculation that we invite readers to undertake on their own.

Coda

THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION PROVED A GREAT EXPERIMENT IN THE introduction of a new, representative form of government. As we have seen, it was to a consequential degree motivated by the interests of a small group of wealthy, elite colonists. Although we focused on George Washington, we could just as easily have made the same case for John Hancock (America’s 54th-richest man ever), Benjamin Franklin (America’s 86th-richest man ever), Thomas Jefferson (the third-wealthiest president, after Washington and Kennedy), Robert Morris, Alexander Hamilton, and others. One charge we have not addressed head-on was the tyranny of which George III was accused. He, too, of course, was a product of his times and not strongly inclined to what we might deem to be democratic, accountable government. Still, tyranny is a harsh charge, and while here is not the place to address it in depth, it is worth looking at a tad of evidence by way of a natural experiment.

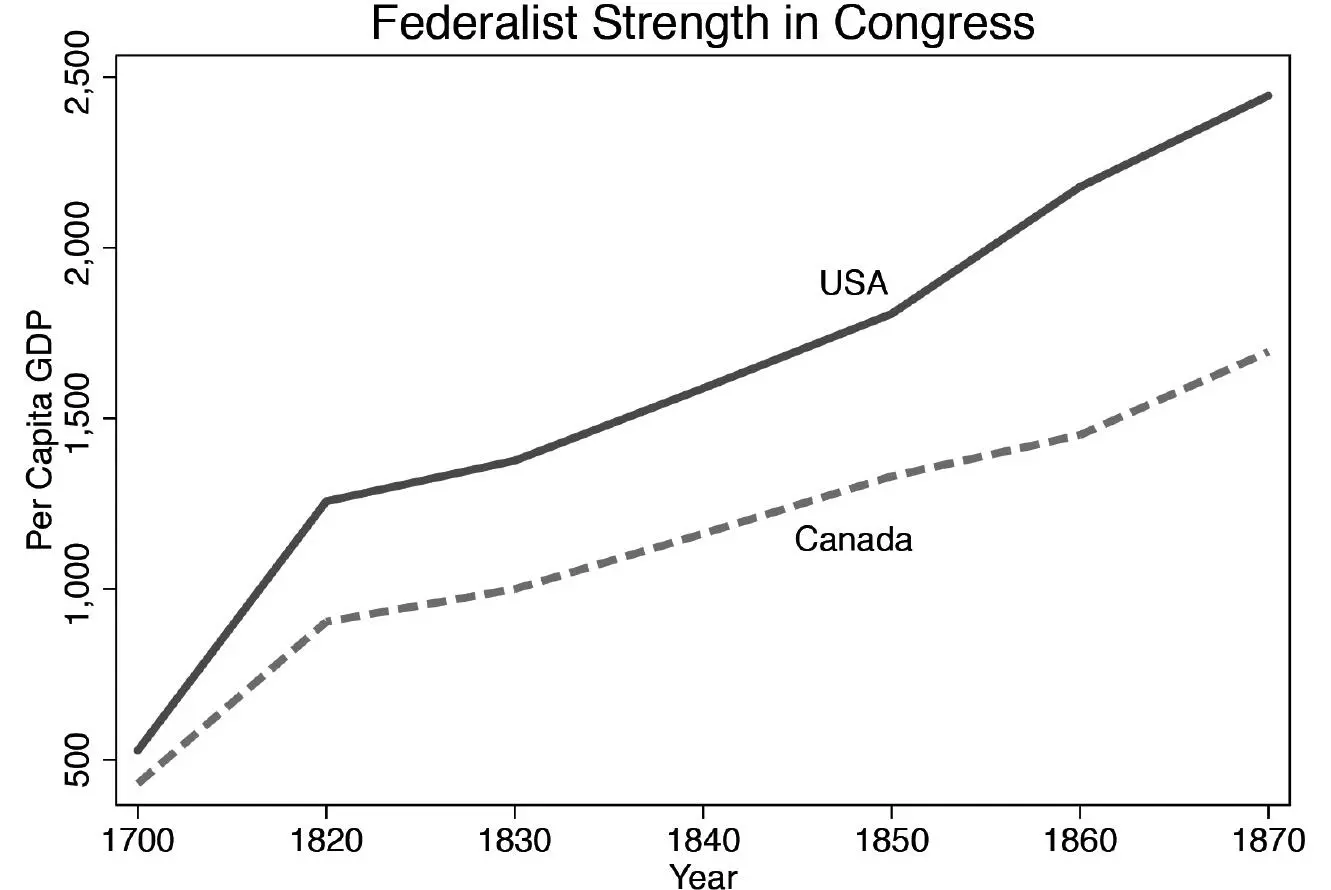

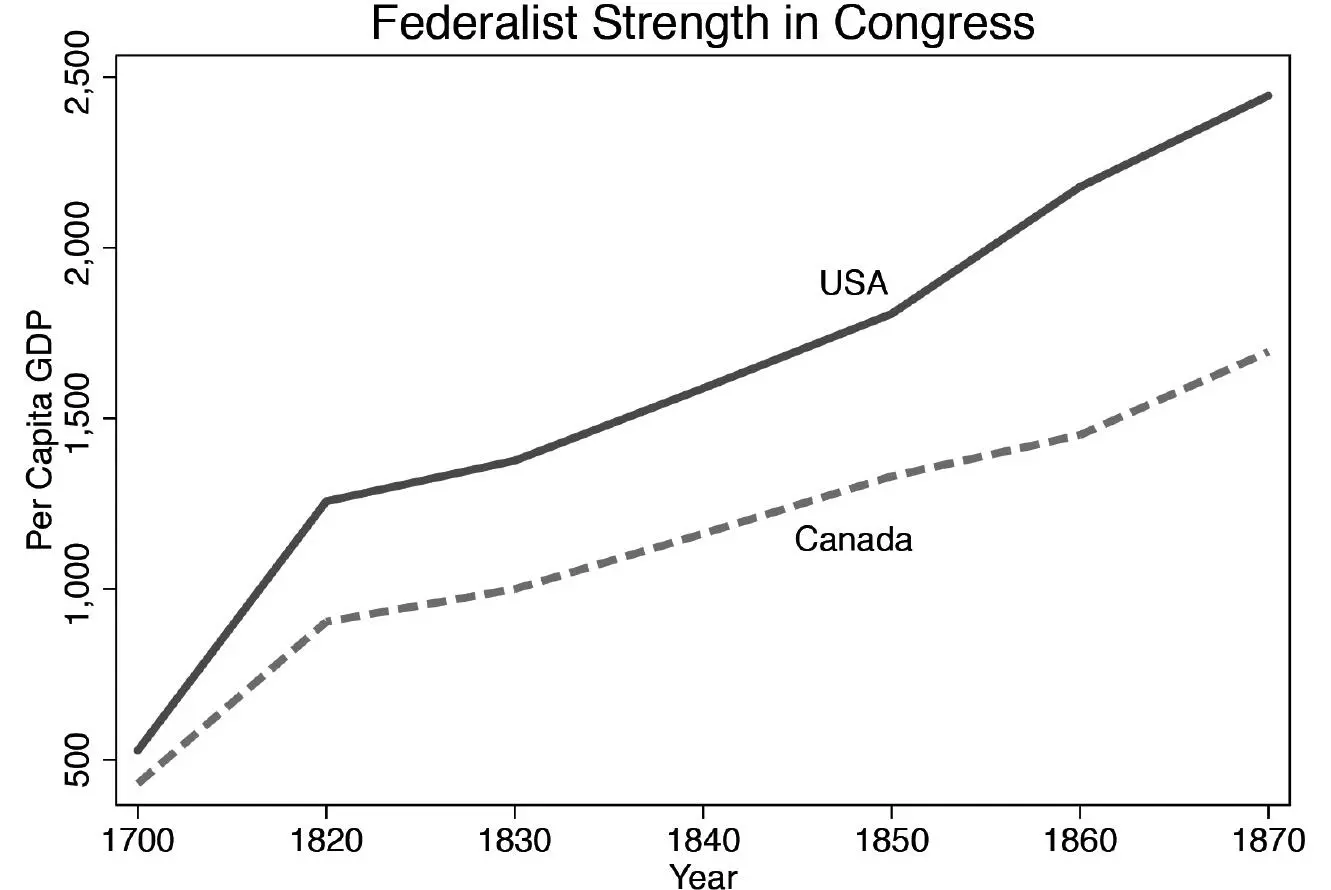

Tyrannical governments generally run their economies into the ground as they focus on securing as much of society’s wealth for themselves and their cronies as possible, always at the expense of their subjects who are not a threat to their hold on power.33 In the case of George III we can compare growth in per capita income in America and Canada as a first-blush indicator of how tyrannical and exploitative his rule was, or wasn’t. Figure 1.1 shows Angus Maddison’s estimates of per capita income in the United States and Canada beginning in 1700 and until it became independent in 1867. Canada lived under George III’s “tyranny” until the king died in 1820. Despite the claim of tyranny, it is pretty hard to see that Canadians suffered terribly compared to Americans. Indeed, the wedge between American and Canadian per capita income does not really start to grow until after George III died and is more likely due to the colder, less hospitable climate in Canada and the paucity of labor, given Canada’s then small population.

Of course, tyranny might have taken many different forms so per capita income—one of the few indicators for which data are available going back that far—is certainly not the only way to assess the alleged oppression of the king. Still, we do well to remember that what we now think of as the early Canadian colonies were given the opportunity to be part of the United States by ratifying the Constitution—and they declined.34 And equally we do well to remember that the revolutionaries were actively supported by about 40 percent of the population, while about 20 percent supported the British. The remainder tried mostly to stay under the radar, if you will forgive the anachronism. It does not seem that the vast majority of people shared the view of the very rich elite whose wealth was at risk from Britain. For most, it seems the king’s rule was not tyranny.35

Figure 1.1. Per Capita Income, United States and Canada, 1700–1870

Chapter 2

Congress’s War of 1812: Partisanship Starts at the Water’s Edge

The truth is that all men having power ought to be mistrusted.

—James Madison

THE FIRST DECLARATION OF WAR BY THE UNITED STATES CAME ON JUNE 18, 1812. In keeping with the stipulations of the Constitution, it was Congress that declared this war against Britain. The decision was not an easy one. Both the House of Representatives and the Senate were deeply divided on the question, with the House voting 70 for and 49 against. The vote in the Senate was 19 yea and 13 nay. The division within each chamber of Congress followed along partisan lines, a fact crucial to understanding the causes and conduct of the war.

Especially by President James Madison’s Federalist opponents, this war came to be referred to as “Mr. Madison’s War.” An equally strong case might be made for thinking of the War of 1812 as “Congress’s War.” Whatever the label and the implied responsibility behind it, we believe that the war had relatively little to do with its frequently attributed causes. It was, instead, largely about two matters. First was the quest for American territorial expansion, particularly, as others have also noted, expansion into what is today’s Canada.1 Second and too infrequently noted, it was about the partisan interest of a segment of the majority party in Congress—the War Hawks. The evidence will show that the War of 1812 was at least as much driven by Madison’s desire to be nominated and reelected as it was by a desire to defend the United States against the threats of Great Britain and its allies.

Читать дальше