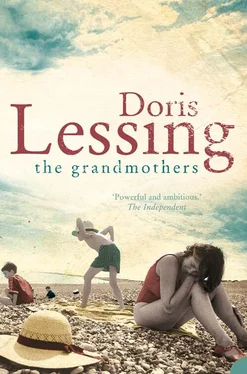

Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Grandmothers

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Grandmothers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Grandmothers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Grandmothers — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Grandmothers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Cities and Thrones and Powers Stand in Time’s eye,

Almost as Ą0II$ as flowers,

Which daily die:

But, as new buds put forth

To glad new men,

Out of the spent and unconsidered Earth

The Cities rise again.

I often recite that to myself when things get rough.’ ‘Yes, sir.’

‘A sense of proportion, one must keep that.’ ‘Yes, sir,’

‘And you do forget, you know, one does forget.’

‘I will never forget, sir, never, never;

‘I see. I’m sorry’ And the Colonel moved off.

On the day the cars came to take the Grants’ guests back to their camp, the air seemed full of rubbish. A wind was busy in the trees, whirling leaves and even small branches out into the roads where people scurried into doorways and holes in a jumble of shops and little houses, and shopkeepers struggled to put up their shutters to save their goods being whisked into the air. Mouths were dry. Eyes stung from the dust.

The cars passed a platoon, accompanied by their corporal, returning from some jaunt associated with the two weeks’ leave. Their eyes were screwed up, their mouths clenched tight, against the sun and the dust. This made them look indignant. Ten expostulating men with the dirt running off them as they marched, and the dust in clouds as high as their knees. The two cars passing raised the dust even more and looking back, the passengers saw a ghostly platoon vanish in a dirty cloud.

The men went to report their return, and James was told that ‘it had been suggested’ he should take a commission and then join Administration. Who had suggested? It could only be Colonel Grant, who was a friend, he had said, of Colonel Chase. ‘Nine to Five,’ thought James. ‘It’s my fate.’

‘Get to Medical tomorrow and then report back.’

James was in a long hut that housed twenty, rather like the hut which was his first home as a soldier getting on for three years ago. None of the men he had been with in Britain were here, but some were fellow sufferers from the ship. On twenty beds, ten to a side, young men sat, listening to the wind fling dust at their shelter.

‘Christ, what a country’

No one disagreed.

They began exchanging news about their two weeks’ leave. All grumbled; nothing to do, a couple of clubs, so called’ making a favour of admitting Other Ranks, a few Eurasian girls, anyone fucking those bints was asking for it, again a shortage of beer, the heat, the heat, the heat.

Then one said to James, ‘We hear we’re going to have to salute you, sir.’

This was unfriendly. James who had listened to routine criticisms, amounting to hatred, of the officers, realised he was now on the other side.

‘So it seems,’ he said.

A soldier gave him a mock salute from where he sat.

‘Enough of that,’ said the corporal,

‘Yes, Corporal.’

‘Administration,’ said James. Ten-pushing.’

‘Better than square bashing.’

‘Oh, I don’t know,’ said James.

‘And how was it at your Colonel’s?’

One of the men in the hut had been among the ten, and now James said, ‘Ask Ted, he’ll tell you.’

‘Fucking awful,’ said Ted, ‘And she’s …’ he screwed his forefinger at his forehead.

‘Suited me,’ said James, annoyed at the ingratitude. ‘I needed a bit of quiet after that voyage.’

‘Quiet,’ said Ted. ‘I’d like a bit of action.’

‘Perhaps they’ll move us on,’ said someone.

‘And perhaps not,’ said James. And he told them what Colonel Grant had said: some regiments were to be kept in India in case of a Jap invasion.

Groans and curses,

‘Roll on the bloody peace.’

In the night, the monsoon arrived and rain battered so loud on their roof that few slept. In the morning the dust of yesterday was in deep chocolate pools where foam scudded as the wind blew.

The men got to breakfast wet and hot. They went to Medical -hot and wet.

‘Hows that knee?’

‘Better,’ said James. It was a lean healthy knee again.

‘I see you play cricket. I’ll get your name put down.”

The doctor prodded James here and there, and said, ‘And now your feet.’

James took off his boots. Liberal applications of a strong-smelling liquid.

‘And your sore throat?

James had mentioned his sore throat to no one hut the Colonel.

‘It’s not too good.’

‘Let’s take a look … yes, I see. It’s the dust. But now the rains have come, it’ll clear up.’

And how did he know? All the personnel, from the Colonel down, were new to India. All were dismayed by it. ‘You’ll acclimatise,’ said this young man, who had read in his textbooks that one did.

The rain stopped. A clean and well-sponged sun appeared.

Hundreds of young men marched and drilled, drilled and marched, the sweat running under the khaki while the sergeants shouted at them that they had gone soft and useless, but don’t worry, we’ll see to that.

James was sent that day to Supplies to get a Second Lieutenant’s uniform, spent time on new boots, and then was in a hut with one other Second Lieutenant, Jack Reeves, who was fitting books into a shelf when he arrived - so, that boded well.

James now said to his new comrade that he had no idea how to behave as an officer.

‘Don’t fret,’ said Jack Reeves. ‘I told the corporal the same and he said, “Just repose on the bosom of your sergeant-major and he’ll see you right”.’

‘Some bosom,’ the rejoinder had to be.

And now both young men were in Administration, with fifteen others, under a Captain Hargreaves who in peacetime had been trying to beat the Slump with a chicken farm in Somerset. The war had saved him from bankruptcy. He was a rather loud, blustering sort of fellow, but competent enough. Every morning he arrived in Administration, took salutes, saluted, and then allotted tasks like someone dealing cards. They dealt with supplies of food, of uniforms, of medical supplies; with the movement of men and with transport. Admin knew everything about the camp and its dispositions, and there was in this an agreeable feeling of power, if James’s temperament had permitted. But his real life, his secret energies, went into waiting for a letter from Daphne. Almost the last thing he had said to her was, ‘You will write, won’t you? Promise.’

But had he actually given her his number? Even his full name? Had she ever called him anything but James?

The measure of his disassociation from reality was that it had taken him weeks to realise that he didn’t have her full name, and certainly not her address. He could not write to her, but she would somehow find out where he was and write. He trusted her to find a way. It had taken the ship three weeks to get from Cape Town to Bombay. Allow a week - well then, two weeks - for delays; he could expect a letter any day now.

No letter. Nothing.

So he had to write to her. But all he remembered of that four days of paradise was stumbling off the ship into Daphne’s arms -that is how it had seemed; a radiance of bliss. A wonderful spreading house on a hillside in a street of such houses, and a garden. A little verandah from where you looked down at the sea, the murdering sea, and where he had danced with her, all night, cheek to cheek. Then that little house in the bushes that smelled of salt, and the waves crashing and thundering all around them.

But no address. Not a number, not the name of the street. The women who organised the hospitality when the troopships arrived, they didn’t take account of the name of this or that soldier: they simply despatched soldiers to willing hostesses. How could he find out her surname? The base at Simonstown? Write and ask for the names of the hostesses who had been so kind when the Troopship X was in?. Careless talk costs lives. He could not put it in a letter. The censor would have it out.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Grandmothers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Grandmothers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Grandmothers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.