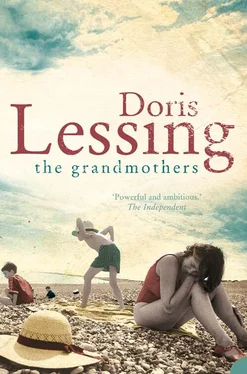

Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Grandmothers

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Grandmothers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Grandmothers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Grandmothers — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Grandmothers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Authority on this second stage of the voyage, remembering the twenty-five madmen they had left behind in Cape Town, the dozens that had gone into hospital to be patched up, and the shocking physical state of the disembarking men, had chosen not to notice that more and more slept on the decks, and, disregarding regulations, simply did not turn up for the ritual of the seawater douches. All that voyage had been very hot. The sickroom was full of cases of diarrhoea, and again officers had to double up so as to provide accommodation for another sickbay. There were always queues for the ship’s doctors. That fruit in unaccustomed stomachs, the feasting and drunkenness at Cape Town, added to the queues for the latrines. If an epidemic broke out - and why not? - what was to be done? Five thousand men, most already run down, many coughing: it was a poor show, and no ship’s officers had ever been more relieved to see a port appear at last.

In the barracks that night the soldiers lay on top of their bedding and cursed, and sweated. The attendant corporals and sergeants, as sick as their men, dismayed and homesick, advised patience, in raucous voices. ‘If you know what’s good for you, you’ll fucking well be patient,’ shouts Sergeant Perkins.

As for James, he did not divide the voyage into two stages, England-Cape Town, Cape Town-Bombay. It had been one long suffering, consuming him, body and soul, interrupted by four days of heaven.

Through the three weeks of die Indian Ocean James, sick and sore, sat with his back against a cabin wall and dreamed … It was a dream, that place, with its mountain spilling cloud like a blessing over its lucky inhabitants. A dream of big cool houses in gardens. He held in his mind that scene of two young women, one dark, one fair, in their flowery wraps under a big tree, that scene; and the nights with Daphne, and one memory in particular, Daphne seeming to shine in the lamplight, her yellow hair spreading on white shoulders, holding out her arms to him. And dancing cheek to cheek. And how the sea had thundered over them, deep in love, crashed and banged and sucked, but then retreated, harmless.

A dream of happiness. He would hold it in his mind and not think of anything at all, only that, until this bloody war ended.

Meanwhile he was in a barracks with fifty men, cursing and scratching and calling out in their sleep, if you could call that sleep, and in the morning he marched with the others to the trains that would take them to Camp X, which it turned out was two days’ travelling away. The conditions on the train matched those on the ship for discomfort but at least a train goes straight, more or less, it doesn’t sway and lurch about. James watched the landscape of middle India go past and hated it. The Cape wasn’t alien, with its oaks and its vineyards and its fruit, he had felt at home in a landscape where nothing said: You don’t belong.

When they at last reached Camp X, somewhere in the middle of India, and marched in their companies on to the parade ground - the maidan - half the camp was of new shiny huts, or sheds. In other words, Nissen huts, and white tents covered the rest of the ground. There was a race, everyone knew, though no one had told them, to get the huts up before the monsoon started. Under their feet as they marched or stood at ease was a powdery dark dust, that puffed up and fell in drifts. The smell, what was the smell, wood smoke and pungency and much else, and the soldiers sniffed and tasted the air, this dusty foreign air, while a sun like a brass band blared down on them.

In lines and in queues the men waited at Medical. Rashes and bad feet, eye infections, stomach disorders, coughs, these soldiers were more fit for an infirmary than for fighting, and James’s knee was up again, like a lump of uncooked dough, with a scar stretched across it. His feet were swollen.

A couple of hundred men were taken to hospitals in the region and the rest were told they would be given two weeks’ leave. If they had nowhere to go - and most would not - they would stay in camp and provision would be made for their relaxation. It seemed there were clubs and bars in town that were prepared to entertain Other Ranks. James was told he was among those invited to stay with a certain Colonel Cram and his wife, to recuperate. That is, he was in a category not bad enough for hospital, but not fit enough for drilling and exercising.

He and nine others were driven off to a big bungalow m a garden full of heavy dark trees that were spattered here and there with pink,

red and white flowers. The smell, the smell, what was it? - a heavy flower smell but the other, pungent, hanging in their nostrils like a reminder of their foreignness. Unknown birds emitted unfamiliar noises. In a garden a black man in a white shirt squatted doing something to a bush. This one had a twist of cloth on his head, but in Cape Town the gardeners in the young women’s gardens wore cast-off good clothes, and old canvas shoes.

Colonel Grant was Indian Army Retired, and a friend of the colonel in James’s regiment, and was now waiting for the war to let him go Home to England. The Grants’ war effort was to entertain soldiers needing a respite. The men did not know each other, though some faces were familiar because of the weeks on the ship. These were all soldiers. Other Ranks, and this was because of a decision by Colonel Grant, since it was always officers who were asked out. James who had been Other Ranks now in various places for two years, had ceased to notice that his way of speaking marked him apart. The sergeants had sometimes picked him out for sarcasm but there was something about how he took this attention that took the fun out of it for them. Here was this quiet, obedient young man, obviously straining to keep up, to hear what was said, to do his best, but not too painfully: James was not victim material. He did not notice now that he was the odd man among these ten soldiers but the Grants did. And he had brought books in his kitbag. The supper was at a long table, once used for formal and probably grand occasions, but now accommodating men not used to them. The food was English, heavy and plentiful.

Mrs Grant was gracious, she was trying hard. A large, red-faced woman, she was uncomfortable in her skin, for she was sweating, and kept holding her face up to the draughts of warm air - not cool but at least moving - from the punkahs. She had patches of dark under her arms, and her pleasant, or at least trying-to-please face smiled conscientiously as she made conversation.

‘And what part of Home do you come from?’

‘Bristol …’ in a strong West Country voice. ‘I’m a plumber by trade.’

‘How mee. How very useful. And do you - I’m afraid I didn’t get your name … ?’

Then it came to James, who sat preoccupied, apart from the others in spirit, which showed on his abstracted face that was frowning with the effort to be here, to be part of things, to behave well, ‘And you, forgive me for not remembering … where are you from?’

‘Near Reading. I was still at college when the war started.’

‘How nice. And what were you studying?’

‘Office management and secretarial.’

Here, Colonel Grant, who had exchanged glances with his wife, because of this more refined voice among the other rougher ones, said, ‘You’ll all have a full day tomorrow. The Medicals will be here early. We start things early here - because of the heat, you know …’

‘It doesn’t matter how early we start, you can never get the better of the heat,’ fretted Mrs Grant.

‘So, I suggest you all get your heads down early and tomorrow we’ll see’

‘I am sure you would all like some coffee?’ Mrs Grant said.

Now the men hung about, exchanging looks. James said he would like coffee, but Colonel Grant said, ‘Probably you’d prefer a good cup of tea. Yes, well, that’s easy. When you are in your billets just clap your hands and ask for char.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Grandmothers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Grandmothers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Grandmothers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.