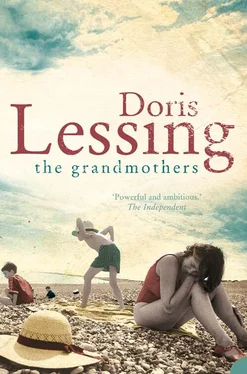

Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Grandmothers

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Grandmothers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Grandmothers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Grandmothers — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Grandmothers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

What was he to do? Never mind, she would write and then there would be an address. Meanwhile he wrote long letters to her, saving them carefully, numbered and dated.

He dreamed of her with an intensity that was like an illness. What he remembered of Cape Town - and with every day the scenes he dwelt on became sharper as he polished them, relived them - was clearer to him than this ugly place full of bored young men. This camp! - what a cock-up (so the men grumbled) - even now not all the huts had been built. Some men were still in tents that had been glaring white but now were stained and brownish, where watery mud lapped around the bases and seeped in through ground sheets. Even now gangs of thin little brown men in loincloths - surely cooler at least than thick khaki? - were hoisting up sheets of roofing or running around with hods of bricks. Everything had a look of impermanence, of improvisation. Everything was difficult: food and water, and basic medicines which had to be rushed, if that was the word, by train from Delhi.

There was grumbling over the food. Curries were making their appearance, but what the men wanted was the roast beef of old England, and that made all kinds of problems. The Hindus didn’t eat beef, and their cows wandered about, skinny and pitiful but sacrosanct, and beef came from the Moslems. Water was the worst: every drop had to be boiled, or otherwise was supposed to have purification tablets, but sometimes the men forgot. There had already been an outbreak of dysentery and the little hospital was full.

In the intervals between storms of rain the dust dried, but what dust …James took up handfuls of it, sifted it between his fingers, a powder as fine as flour. ‘The spent and unconsidered earth,’ he murmured: that is where Kipling got his line, from the lifeless, fine-blowing soil of India. This soil wouldn’t be able to grow the tiniest weed, it was so spent.

He passed requisite time in the Officers’ Mess, and its rituals, he was not negligent. He was determined not to be thought an oddity.

And yet he knew he must be, because he sometimes didn’t hear when people spoke to him. He was happiest with Jack Reeves, in their hut, reading, or talking about England. Jack was homesick and said so; James was sick with love, but did not confide in his friend. No one could understand, he knew that.

No letter came from Daphne. Letters from his mother, yes, with messages from his father, heavily censored, but Daphne was silent.

In his position in Administration he learned that another troopship was arriving, not destined to discharge its load at Camp X but at Camps Y or Z; fifty men would arrive here, to replace the twenty-five taken off at Cape Town and the casualties since. There had already been funerals; the Last Post had sounded over Camp X. Some sick men would never be fit for duty and would have to wait until the end of the war to get home. As Colonel Grant had said, India took it out of you.

This camp was so charged with homesickness and longings that it could have lifted up into the air and got home to England without the benefit of ships, or even of aeroplanes - which were for the sick. So James jested with Jack: it was a fantasy that was enlivening the camp for a while.

The new arrivals off the unnamed troopship had spent three days in Cape Town: bad luck would have taken them to Durban, but it was Cape Town. James spoke to one, and then another, until he found one who had been a guest, but did not describe anything like the houses and gardens James remembered. Then at last James did, by diligent pursuit, hear that yes, he had got lucky. The man had been whisked off to a house on a hill, with a garden and …

‘What was her name?’

‘Betty, she was called Betty. And what a party, the food, the drink.’

‘And was there another woman there? A girl with fair hair?’

‘There were a lot of girls, yes. What was her name?’

‘Daphne, her name was Daphne.’

And now at last James heard: ‘Yes, I think there was. Yes. Yellow hair. But she wasn’t there much. She was pregnant. Must have popped by now.’

And no matter how James pressed and urged, that was all he could find out.

Pregnant. Nine months. It fitted. The baby was his. It had to be. Funny, he had not once thought of a baby, though now he felt ridiculous that he hadn’t. Babies resulted from lovemaking. But that was a bit of an abstract preposition. His lovemaking, with Daphne, what did it have to do with the progenitive? With baby-making? No, it had not crossed his mind. Now he could think of nothing else. Over there, across all that sea, beyond the appalling Indian Ocean, was that fair city on its hills, and there in that house was his only love with his baby.

He tried again with his informant. ‘What was the address? Where was the party?’

‘No idea. Sorry’

‘What was the fair woman’s name?’

‘I thought you said Daphne.’

‘No, her surname.’

‘No idea.’

‘Did you get the name of your hostess, the dark one, Betty?’

“I think it was Stubbs.’

‘No address?’

‘Sorry, I never thought to keep it - you know, they just drove us up there and then back again.’

‘Is she going to write to you?’

‘Who?’

‘Betty, Betty Stubbs, is she going to write you letters?’

‘No, why should she? There were dozens of us, she isn’t going to write letters to every poor sod she invited to a party;

But James was better off by one name. He had had Betty, and now he had Stubbs. Her husband was a captain at Simonstown and a friend of Daphne’s husband.

Bringing himself back from his world of dreams to reality (‘what they call reality’ - he knew how his state would be criticised, if anyone guessed it) he decided that he could not write to this husband of Daphne’s friend Betty and say, ‘Please give the enclosed to your friend and neighbour Daphne. After all, Daphne did have a husband. She had said so. But she could have had two or three husbands and they would not affect the secret life he shared with Daphne and which he knew - she must - share too. No one could have lived through that time and not for ever be changed - that he knew. But he did not wish to harm her.

He wrote: ‘Dear Captain Stubbs, I was one of the lucky men who disembarked for four days at Cape Town some months ago. I was the guest of Daphne, who lives next door to you. I would be grateful if you could drop me a line with her address. Sincerely. Second Lieutenant James Reid.’

This innocuous letter, giving nothing away - he was certain - was sent off, through the usual monitored channels. The very earliest he could expect a reply, even if everything went perfectly, was a month, let’s say six weeks.

The six weeks passed.

In the intensity of concentration of his dream James hardly noticed that the rains had stopped, the earth was parching, the heat was beating. Outside his hut someone had thrown down a mango pip which had rooted and was already a vigorous six inches of growth. So the soil of India might be unconsidered but it certainly wasn’t spent.

James sent another letter to Simonstown. After all, letters went astray, ships sank, his first letter to Simonstown had been like a paper dart with a message on it thrown into the dark.

Months passed. A letter came. It read:

Dear James,

Daphne has asked me to write. She says please don’t write again. She is very well and happy. She is having another baby, which will be born by the time you get this, I expect. So she will soon have two children. Joe is named after his father, and if it is a little girl -Daphne is sure it will be - her name will be Jill.

She sends greetings.

With our best wishes,

Betty Stubbs. Daphne Wright

Greetings! She sent greetings! James dismissed the greetings - that is not what she meant, it is what she had to say.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Grandmothers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Grandmothers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Grandmothers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.