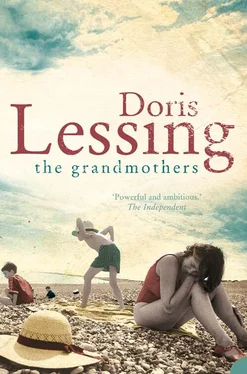

Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Grandmothers

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Grandmothers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Grandmothers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Grandmothers — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Grandmothers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

To his intimate memories, little pictures, the two lovely women in their flowery wrappers under a tree, Daphne in a hundred different guises, all of them smiling, he now added Daphne with a little boy, a fair pretty child, absolutely unlike the dark babies with their golden bangles on chubby wrists that he saw on their mothers’ hips, on the roads, in the shops, in doorways. When the war was over he would go to Cape Town and claim Daphne, claim his son. He knew he rejected all these pleasant Indian babies because their mothers weren’t Daphne.

War is not a continuum, but long periods of inaction and boredom interrupted by fits of intensive activity; that is to say, fighting, danger, death, and then boredom and quiescence again. So the news has always come from the fronts. ‘How was the war for you? “God, the boredom, that was the worst. “But I thought you were at Dunkirk … Borodino … in Crete … in Burma … the Siege of Mafeking?’ ‘Yes, but the bits in between, my God, the boredom, I wouldn’t wish that on my worst enemy.’ In Camp X boredom was like an illness, one of those diseases where a virus lays your immune system low. Boredom alleviated by a fever of rumour-mongering.

Rumours in wartime: now that’s a theme. Prognostications that have the sheen of dreams, bred of terror and loneliness and hope from unlikely places in the human mind, seethe and simmer and then spill out in words from the mouth of some careless talker in a pub or barracks, and then they fly, fly from mouth to mouth, until in no time, a day, a week, the truth is out: ‘We are being posted to Y Camp, no, to Z camp, to be nearer when the Japs attack. “They’re going to attack next week, that’s why the 9th Empire Rifles are going up there.’ ‘We are being sent to Burma - the Adjutant told Sergeant Benton. “This camp is too unhealthy, its going to be closed down and we’ll be sent to the hills .”They’ve hushed up an outbreak of cholera. Keep that under your hat or we’ll have a riot.’ ‘They’re putting sedatives in our food to keep us quiet.

Boredom and rumours.

The Japs were closer: they swarmed over Asia, but it was not James’s regiment sent to fight them. James’s regiment in Camp X, where James dreamed and had his being, was sent nowhere. Life went on, day by uncomfortable day, the hot winds blew about, saliva tasted of dust and the eyes stung and then the monsoon rain … the third. I943. The soldiers saw how Indians came running from their houses and shops and held up their arms to the rain and turned themselves about, singing. No soldiers ran from their huts to stand in the rain; it was their job to give an example, to behave properly, preserve decorum.

Colonel Grant and his lady had invited James to the odd weekend. The Colonel had taken a shine to James, whose diffidence diagnosed things thus: I suppose he likes having someone to talk to about Kipling.

A conversation had taken place. Mrs Grant said to her husband, ‘I don’t want any more of these Other Ranks. They don’t behave. Last time there was vomit all over the place.’

‘You exaggerate, my dear’

‘No. They’re not of our class, and they don’t really enjoy coming to us.’

Colonel Grant suspected this was true, but he said, ‘They’re having a thin time of it out here. We should do what we can.’

Tin putting my foot down, only officers, I’m simply not having it.’

There were hinterlands here. Long ago Colonel Grant had been a clever poor boy who got a rare scholarship to Sandhurst, which, as he progressed up the hierarchy, was proved amply justified. His had been a fine career. But he had not been of his lady wife Mildred’s class, not to start with. That is why the Grants had always invited Other Ranks. Not any longer. Mrs Grant was putting her foot down.

‘I don’t mind that boy, what’s his name, James something, he knows how to behave.’

‘He’s an officer now, my dear.’

‘Well, there you are.’

Ten young officers, James one of them, had spent a long weekend with the Grants and behaved well enough, though they, like the earlier guests, took themselves off into the town’s clubs.

James did not.

Colonel Grant said to James, while they sat companionably on the verandah, a tray of tea between them, ‘James, tell me, what is the talk in camp, about things in general?’

‘You mean, being kept here in India, doing nothing? ‘This was direct, and it was bitter, and not only on bis own account.

‘Yes, what are they saying?’

Now the Colonel must know what ‘they’ were saying, since his friend Colonel Chase heard it all, in the Officers’ Mess. Had he forgotten James was no longer with the ordinary soldiers?

‘When I was in with the men, there was a lot of grumbling. They don’t like it. But you know, the men grumble about everything.’ Yes, the Colonel did know, he hadn’t forgotten. ‘It seems to me, sir, that the men dislike officers as a matter of form … but is that what you were asking?’

What Colonel Grant was asking came from many levels and motives in him. He and Colonel Chase had sat together, talking intemperately - for them - about disaffection, and feeling that they were out of touch.

‘In the Officer’s Mess - is there bad feeling? Dangerous bad feeling?’

Since Colonel Chase heard the kind of thing said, this must be a question of interpretation: and James was startled.

‘I don’t like politics, sir, I never did.’

To say that, straight out, wasn’t something he would have done in the mess.

He had, at the beginning, said, ‘I’m not interested in politics,’ as he might have said, ‘I don’t take sugar in my tea.’

He could have said he was Conservative, or - daringly - that he intended to vote Labour, but not, that he was uninterested, any more than in the time of, let’s say, Luther’s Theses, someone might have said, I’m not interested in religion.

To be not interested in politics: that meant he was callously indifferent to the fate of humanity, at the very least misinformed. On that early evening a dozen young men set themselves to inform him. And so he had evolved some polite ways of indicating interest without committing himself.

But this explosion of interest in his lack of proper feeling had made him think back to the glorious days of I938. Now he knew that the intense political feeling of that time had not been the nation’s usual condition. Mostly left-wing feeling. There had been a boiling up of political thought, because of the Spanish Civil War, because of the Slump and the poverty, because of the threat of the coming war and so there had been all those politics, mostly left-wing. He had gone through it listening, but reading poetry.

In the Officers’ Mess most of the young men were left-wing, in various ways, but the talk was - loudly - about India. The young officers, not the older ones. The whole sub-continent was effervescing with talk of freedom, freedom from Britain, and here, in Camp X, their main task was to suppress it.

What had Colonel Chase said to Colonel Cram? He would have talked of troublemakers, Bolsheviks, even communists. About the Fifth Column, and possibly there might even have been talk of courts-martial.

‘You may not like politics, James, but I don’t imagine you can avoid them.’

James said truthfully, ‘I never think about it.’

Now the Colonel protested, in an old mans aggrieved voice, ‘Does what we’ve done here in India mean nothing to you? We’ve built all these fine railways, we’ve built roads, we’ve kept order …’ He had to stop. Order was not the word for what was happening now: agitators everywhere, the Congress, people in prison. Then, ‘Does the British Empire mean nothing to you, James?’

‘The Captains and Kings are going to have to depart, sir, that’s what I think.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Grandmothers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Grandmothers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Grandmothers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.