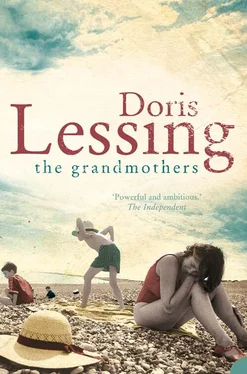

Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doris Lessing - The Grandmothers» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Grandmothers

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Grandmothers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Grandmothers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Grandmothers — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Grandmothers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Daphne collapsed: her eyes closed.

And now Betty and Sarah stood together: slowly, carefully, their eyes met, and held.

When Daphne had arrived in South Africa she had criticised Betty, the South African born and bred, for behaving in front of her staff as if they did not exist. One day Betty had come out of her bathroom naked and walked across her bedroom in full sight of the gardener who was at work just outside the french windows. She had stood there and talked, brushing her hair, and turned about, as if the man were not there, and when Daphne told her off, she realised for the first time that her servants had become as invisible as mechanical servitors. They were paid well - for this was liberal Cape Town (‘We pay our people much better than they do in Joburg, fed, taken to the doctor, given generous hours off. But they were not there for Betty, as human beings. Remorse, if that was the wort!, had adjusted her behaviour and her thoughts, and she became noticing and on

guard, watching what she did and what she said. But she could not think of anything apt for this situation. The four maids, hers and Daphne’s, were friends and knew the other maids along the street: this went for the gardeners. Hy now all of them would be discussing Daphne and the soldier. Any one of them might tell Joe.

‘Mrs Wright is very sick,’ said Betty at last, knowing she was blushing because of the feebleness of it. And it had sounded like a plea, which she didn’t like.

Sarah said, ‘Yes, medem.’ Compassionate, yes: but no doubt there was derision there, a forgivable allowance, in the circumstances.

‘Yes,’ said Betty. She was in the grip of the oddest compulsion. Like Daphne, she could have tugged at her locks with both hands; instead she passed her hands across her face, wiping away whatever expression might be there - she didn’t want to know. And now, she couldn’t help herself, she let out a short barking laugh and clapped a hand across her mouth.

‘Yes, medem,’ said Sarah, sighing. She turned and went off.

‘Oh, my God,’ said Betty. She took a last hopeless look at her friend who was lying there, struck down. Somewhere over the horizon, that soldier was on his way north into the dark of the Indian Ocean.

Betty went to her house, sat on her dark steps, and in her mind’s eye persisted the sight of Daphne, lying white-faced and hardly breathing.

‘Oh, no, no, no, no, no,’ said Betty wildly, aloud, and sank her face into her hands, ‘No. I don’t want it. Never,’

Sometime later Joe’s car came up, Betty went to intercept him. At once he began talking. ‘Betty, Henry won’t be back tonight, he asked me to tell you, it’s been a real dingdong these last few days, you’ve no idea, getting in enough supplies and everything, it’s not been easy - for the ship, you know, the one that’s just left.’ He was talking too loudly, and walked past her up his steps, and turned.

And stood talking into the garden, where she stood, ‘We lost a ship - the Queen of Liverpool - no, forget I said that, I didn’t say it. Five hundred men gone. Five hundred. It was the same sub that was chasing the - the ship that’s just left. Hut we got her. Before she sank she got the sub. Five hundred men.’ He was now walking about, gesticulating, not seeing her, talking, in an extreme of exhaustion. ‘Yes, and the ship that’s gone, they left us twenty-five. They’re in a bad way. They’re mad. Claustrophobia, you know, stress. I don’t blame them, below the water line, well, they’re in hospital. They’re crazy. Henry saw them. When he gets home, he’ll need looking after himself. Five hundred men - that’s not something you can take in. Henry hasn’t really slept since the ship got in.’

‘Yes, I see.’

‘So, you must make allowances. He won’t be himself. A pretty poor show all around, these last four days. And I’m not myself either.’ And he went striding towards the bedroom.

‘Daphne’s not well. She’s taken a sedative.’

‘If there’s any left, I’ll take one too.’

Hetty went with him into the bedroom.

The sight of his wife stopped him dead.

‘Good Lord,’ he said. ‘What is it?’

‘Probably some bug. Don’t worry. She’ll be all right tomorrow I expect.’

‘Good Lord,’ he said again. She took pills from the bottle by the bed, gave them to him, and he downed them with a gulp from Daphne’s glass.

He sank down to sit on the bed. ‘Betty,’ he said, ‘five hundred men. Makes you think, doesn’t it?’ He stood up, pulled off his boots, first one, thump, then the other, thump; walked around to the other side of Daphne, lay down and was asleep.

Betty went to tell the maids that no supper would be needed. ‘Go off home. That’s right.’

‘Thank you, medem.’

Betty returned to stand near the bed. Daphne had not moved.

Joe lay there, beside his wife, Good-fellow Joe, everybody’s friend, rubicund and jovial, but there he lay, and Hetty would not have known him. He kept grimacing in his sleep, and grinding his teeth, and then, when he was still, his mouth was dragged down with exhaustion.

Betty switched off the light. She returned to her house over dark lawns and sat for a long time, in the dark. Four days. There had been so much noise; soldiers with their English voices, telephones, cars coming and going, dance music, the same tunes played over and over again on die gramophone, while feet in army boots scraped and slid, but now the noise was subsiding, another voice that had been speaking all the time was becoming audible, in an eloquence of loss, and endurance. Four days the troopship had been in. A long way off, on the other side of a chasm, of an abyss, smiled life, dear kind ordinary life.

Down the gangways they came, between the guns that had been ready to defend them all the way from Cape Town, Hues of men, hundreds, to form up in their platoons and companies on the quays, where James was already standing at ease, though at ease he was not, for his feet hurt like, it is safe to say, the feet of most of those young men, some of whom had been there for over an hour, under an unwelcoming sun. These soldiers were not in as bad a way as getting on for a month ago, in Cape Town. Beneficent Cape of Good Hope had loaded the ship with food, and above all fruit. Foot boys who had scarcely tasted a grape in their lives had consumed luscious bunches until the bounty ran out. Three weeks this time, not a month, and the Indian Ocean had been kind except for a four-day storm halfway across, when conditions had been similar to

those in the Atlantic. James stood narrowing his eyes against the glare, holding himself so as not to faint; and he watched the great ship and, if hatred could kill, then it would have sunk there and then and be gone forever.

It was very hot. The air was stale and clammy. Thin dark men in loincloths hurried about being told what to do by dark men in uniform, who were being supervised by white men in uniform. No smell of sea now, though it was so near, only oil and traffic fumes. At last the endless lines did end, while men were still forming into their companies. Some had already moved off, to the accompaniment of the barking sounds of the sergeants, which James now found soothing, being reminders of order and regularity. James’s company were marched to a barracks, where they were fed, and showered off the seawater which on some skins still festered. Hundreds of naked young men, but while they were in nothing like as bad shape as in Cape Town they were still the walking wounded, patched with red rough skin and fading bruises. They would be sent to the train tomorrow, which would take them to their destination: unnamed. The name, its harsh alien syllables was whispered about through the hundreds of soldiers who were already thinking of it as a haven where they would at last keep still, lose the sway of the ship. Camp X was what they had to call it. The smell in the barracks was enough to make them sick, despite the showers.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Grandmothers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Grandmothers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Grandmothers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.