‘How much farther to Tidore?’

‘Another hundred leagues, maybe more.’

Dan gazed downwind. A large grey seabird, an albatross, cruised back and forth, unconcerned by the gale, the tips of its immense wings skimming the surface of the sea.

‘The vessel will never make it,’ the Miskito said in a matter-of-fact tone.

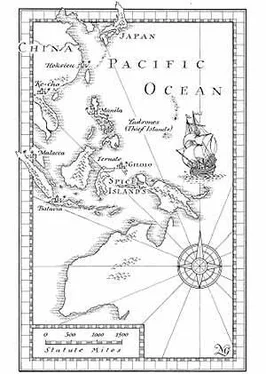

Hector thought back to the calculations he’d made, estimating and re-estimating the distance to the nearest land. He wasn’t confident the ocean currents had not affected their course, and he doubted the accuracy of the chart that Vlucht had on board. He marvelled once more at the way the Chamorro makhana had been able to navigate. ‘Our best chance is to try to beach the ship as soon as we sight land,’ he said at last.

He was aware of Maria approaching up the companionway. She was bare-headed, and her bodice and working skirt were rumpled and stained. She’d found a man’s large shirt, which she wore loose as a gown, and the sleeves were rolled up to her elbows. The expression on her face was infinitely weary, resigned. Since coming aboard the Westflinge , Maria had spent all her time with the sick in the forecastle.

‘There are two corpses to be dealt with,’ she said simply.

‘We must put them overboard without delay,’ he said, knowing he sounded heartless.

‘Then please do so,’ she said, turning away.

He heard the catch in her voice and answered, raising his voice so that, without meaning to, he sounded harsh. ‘Maria, every hour we keep the bodies on the ship, we risk spreading the sickness. And depressing the surviving invalids.’

She wheeled around. There were tears in her eyes. ‘This voyage began so well. When we set sail with the Chamorro, I was so excited and full of hope. But the last few days have been a nightmare. Everything we do seems so pointless.’

A sense of helplessness swept over Hector. He dreaded telling her the full extent of their difficulties – that the ship was likely to founder. ‘Maria, we all have to be patient . . . as you were at Aganah. Things will change, I promise.’ He sounded so feeble, he thought. He was stating the obvious.

She put a hand to her cheek. Hector couldn’t tell if it was to wipe away a tear or raindrops. He was aware that Dan had moved away to a tactful distance.

‘In Aganah it was different,’ she said. ‘I got used to waiting and had set myself a deadline. I knew it would all come to an end, one way or another. But now, I’ve allowed myself to hope, and that makes the disappointment and setbacks harder to bear.’

‘Maria, you’ve done all you could to save those two men. They were mortally sick when first we came on board. I promise you we’ll head for the first land we see. If you can keep your patients alive until then, they should survive.’

‘And how long will that be?’

‘One or two days at most.’

‘I pray you’re telling me the truth,’ she answered. She turned and made her way to the far rail and stood facing out to sea, her hands gripping the wet rail, her knuckles white.

Hector nodded to Dan and together the two men descended quietly to the main deck and entered the cabin. It still reeked of sickness and damp, but it was much more orderly and cleaner than before. The invalids in their cots and on the floor rested quietly on mattresses. Hector looked around, wondering where to find the dead men. One of the invalids in a bunk struggled up on an elbow, watching him silently. He moved his eyes deliberately, looking across and down. Two long shapes lay on the floor, covered with blankets. Without a word, Hector took one end of the nearest bundle while the Miskito picked up the other. Together they carried the corpse out on deck. It was a few steps to the gap in the rail they had cut when they dumped the cannon overboard. The burden between them was very light. ‘Wait a moment,’ said Dan as they reached the gap. They laid the dead man gently on the deck.

Jacques was nowhere to be seen, but Stolck had noticed what they were doing, and walked across and stood looking down at the corpse.

‘Would you care to say a prayer over him?’ Hector asked Stolck.

‘I’m no pastor,’ answered the Frisian in a defensive tone. ‘But I’ll help you carry out his companion.’

With Stolck’s assistance, Hector brought the second corpse out from the forecastle.

Dan had disappeared down into the hold and now he reappeared with several fathoms of cord and two of the remaining ballast stones. ‘We won’t be needing these,’ he said as he knotted a web of cord around each rock, then fastened the weights securely to the dead men’s feet.

As soon as he was done, they slid the dead men overboard without ceremony. The whole business had taken no more than fifteen minutes. When Hector looked up, he saw Maria still standing at the rail, her back to the ship. She was drenched, her clothes plastered against her body, and she still gripped the rail with both hands.

THANKFULLY THE RAIN eased early on the following day and the visibility improved. It revealed a dark smudge on the horizon to starboard. At first it was so indistinct it could have been a low bank of cloud, but as the hours passed it gradually became evident that land lay in that direction.

‘What do you make of it?’ Jacques asked Hector as they stood on the quarterdeck, gazing at the faint shadow. The sea had calmed, but this only served to emphasize that the Westflinge was almost dead in the water.

‘Difficult to tell. But my guess is that it’s one of the Spice Islands, possibly the north end of Gilolo.’ Hector turned his attention to a small, yellow-brown clump of floating seaweed. It was nuzzling against the side of the ship. ‘If I’m right, we’ve drifted farther south than I’d hoped and we have no hope of reaching Tidore, not with the ship in this condition.’

The clump of seaweed had barely moved an arm’s length along the hull. The Westflinge was virtually stationary.

‘Is there a harbour on Gilolo?’ Jacques asked.

‘Not on this side, according to Vlucht’s chart. The east coast of the island is very little known. Nevertheless, I propose we run the ship aground there. At least we have a chance of getting everyone ashore, including the sick.’

‘And if we come upon a coast full of rocks and reefs?’

Hector shrugged. ‘We have no choice.’

Slowly, desperately slowly, the Westflinge edged closer to the land. The wind fell slack, barely filling the sails, and now only the current carried her along. The coast crept by, low and featureless and covered with dense jungle. There was no sign of a barrier reef, fortunately. The ship was so low in the water that she did not answer to the helm at all. Those on board could only watch and wait.

By dusk less than a mile separated the ship from the shore and she drifted onwards through the darkness. A heavy overcast obscured any light from the moon. It was pitch-black though close to dawn when they finally heard the low, grinding sound as the Westflinge ’s keel touched. There came a series of shuddering, scraping noises as she slid gently on to her final resting place. A last muffled groan of timber, and all forward motion ceased. The only sound was an occasional low thump and tremor as a slight swell lifted and dropped the vessel, still upright, farther on the seabed.

They all waited on deck to see what daylight would reveal.

The Westflinge had gone aground a quarter of a mile from land. The water around her was clear enough to see the wavering outlines of grey and brown coral heads on which she was stranded. Directly ahead was a long, straight shoreline where a solid mass of vegetation came right to the water’s edge, the branches of the larger trees overhanging the sea. The same dense green wilderness extended inland across broken country, and without a break as far as the eye could see. Except for the slow drift of pale-grey shreds of morning mist curling up from the jungle canopy, everything was silent and still.

Читать дальше