‘Where’s Maria?’ Hector asked Dan, catching him by the arm.

‘She went off for a walk in the jungle,’ the Miskito answered. ‘She cannot have gone far.’

Hector turned to the Omoro chamberlain. ‘One of our party is missing,’ he said.

‘We cannot delay,’ Ciliati Mansur answered. ‘The Sultan expects our return in time for maghrib, the sunset prayer.’

‘Please allow me a few moments,’ Hector begged.

Fortunately it took him no more than a few minutes to locate Maria. She had only gone as far as the tree, hoping to catch another glimpse of the remarkable birds. When Hector returned with her, the chamberlain was taken aback.

‘You did not say that your travelling companion was a woman,’ Mansur said in surprise.

‘She is my betrothed,’ Hector answered.

‘But you are not yet married?’

‘No.’

‘And her family permits her to travel without female companions?’

‘That is our custom,’ Hector answered.

The chamberlain sucked in his breath softly. Hector guessed Maria was the first European woman he’d ever seen, and he didn’t approve of her lax foreign ways. ‘Then she must remain in the cabin until we arrive home,’ he said firmly.

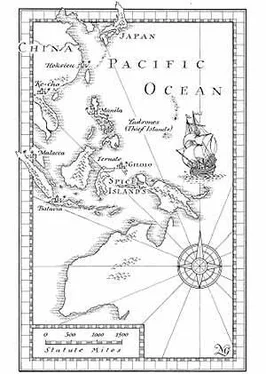

THE JOURNEY to the Sultan’s capital proved to be a short one. The kora kora’s crew looked to be frail, but they kept up a brisk pace. Four hours of steady paddling along the coast brought them to their destination, and Hector used the time to question Ciliati Mansur about what to expect. The Sultan of Omoro, the chamberlain informed him, had ruled for nearly forty years over a small coastal kingdom that was once rich and powerful, but now increasingly impoverished. Mansur blamed this decline on the shadow of the Sultans of Ternate and Tidore. They had intercepted the only trade that brought much money to Omoro – the sale of exotic bird skins.

‘We call them manuk dewata, “God’s Birds”,’ explained the chamberlain. ‘In truth, Allah put the creatures in our jungle so that we can have something to offer in exchange for the items we lack – guns, powder, and so forth. Traders come from as far afield as Malacca to buy our bird skins.’

‘Are the feathers really that precious?’ asked Hector.

A slight smile twitched the corners of Mansur’s mouth. ‘Yes, thanks to the vanity of man. We pretend the birds are enormously difficult to catch. We claim they have no legs and so they can never alight on land, but soar up into the sunbeams and catch and fix the colours of the rainbow in their plumage.’

‘I’ve seen the creatures settle and squabble on the branches of a tree, and they were noisy and very down to earth,’ said Hector.

‘Then you are one of the very few outsiders to have witnessed such things,’ said the chamberlain. ‘In reality the birds are not so difficult to take. The hunters spread a sticky gum on the branches where the birds gather, and the creatures are trapped. The bird catchers wring their necks, strip off the skins with the feathers attached and bring them to the Sultan’s agent. He alone has the right to sell them on to the Malay traders. That tale of the legless birds started because the hunters cut off the birds’ legs while they are skinning them.’

Hector glanced across to the young prince seated on a cushion by the door of the cabin into which Maria had gone. ‘Does the Sultan have other sons?’ he asked quietly.

‘Prince Jainalabidin is the Sultan’s only male child. Allah withheld that blessing for many years. Our Sultan is old enough to be Prince Jainalabidin’s grandfather.’

Hector remained silent. When both he and Dan had been prisoners of the Barbary Turks, he had observed how greatly the Muslim rulers valued having a male heir.

‘When will I be allowed to speak with my betrothed? I have to reassure her that all is well,’ he said. Everything had happened so quickly that he hadn’t had a chance to exchange more than a few words with Maria, and she’d been confined to the cabin since coming on board.

‘That will be for the Sultan to decide,’ the chamberlain answered blandly. He paused, as if considering what to say next. Then he added in a cautionary tone, ‘When you meet His Highness, please remember that he is full of years, and that old men are given to strange fantasies. Their decisions sometimes seem erratic.’

Hector was left wondering uneasily whether his fate, and that of his companions, would now depend on the whims of a capricious dotard who ruled a bankrupt kingdom.

THE KORA KORA turned into a narrow, steep-sided river mouth on which the Sultan’s capital was situated. The place, Pehko, was a ramshackle settlement of bamboo and thatch houses. The nearest were little more than shacks poised on stilts over the grey-green surface of the fetid backwater. As the kora kora glided into harbour, Hector could see women and children standing on the rickety platforms, their arms held up to shade their eyes as they gazed at the return of their menfolk. A strong odour of drying fish and rotting debris mingled with the scent of wood smoke from the cooking fires and drifted across the water. Chickens and ducks foraged along the foreshore, where dozens of small dugout canoes were drawn up, and festoons of nets hung to dry on posts driven into the mud. He glimpsed more thatched dwellings farther up the slope, half-hidden among groves of tall trees, their foliage a deep, luxuriant green with glimpses of red and yellow fruit. There were only two buildings of any size. One was the mosque, for he could hear the call to prayer from its roof. The other was an untidy sprawling structure situated on high ground behind the town, where a curve of hillside gave a view directly down into the estuary. Even at a distance he could see the extravagant profusion of flags and banners sprouting from every corner and angle of the building, along the ridge of the roof and from triple flagstaffs in front of the grandiose portico.

‘Kedatun sultan, the palace of the Sultan,’ murmured the chamberlain as the kora kora came to rest against the wooden pilings of a jetty on the right bank. On the dockside six Omoro warriors were waiting. They were armed with spears and shields trimmed with horsehair. Behind them stood a bizarre-looking vehicle. The two rear wheels were almost the height of a man, their spokes and felloes painted in blue and green patterns, now faded and peeling. The two front wheels were one-third of the size and similarly decorated. Slung between them by leather straps hung a gilded sedan chair, its door panels showing pictures of leaves and flowers. But instead of horses between the shafts, the contraption was to be pulled by four servants, barefoot and wearing loincloths. On their heads, in imitation of horse decoration, they wore long, nodding plumes, orange and black, thrust into their turbans. As he watched, the young prince disembarked from the kora kora and stalked across to the carriage. The door was held open by a kneeling servant. The small prince stepped inside, and a moment later the team of humans were trotting away, dragging the carriage up towards the Sultan’s palace on the hillside.

A discreet nudge from Dan brought Hector’s attention back to his immediate surroundings. The chamberlain was indicating that it was time for him and his party to disembark and follow him. Hector turned to look for Maria, but it was too late. A cordon of armed Omoro already blocked his view and they were hustling Vlucht and the other Hollanders on to the jetty. Hector had a feeling that while he and his friends were not exactly prisoners, neither were they free to do as they pleased. He tried to push through the cordon back to the cabin, but his path was barred. Thwarted, he ran to catch up with Mansur, to ask again if he could speak with Maria. But Mansur was already at the entrance to a long, low building erected on pilings over the water.

Читать дальше