Sworn brother

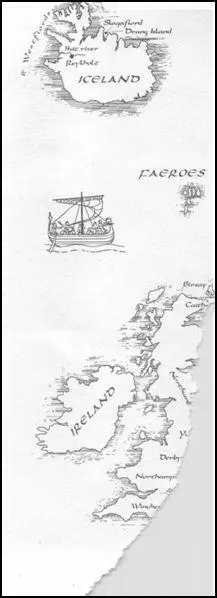

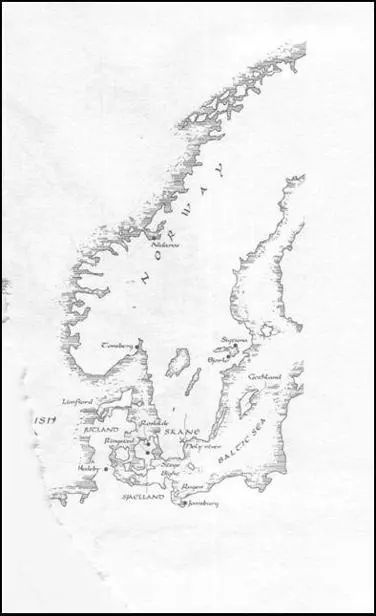

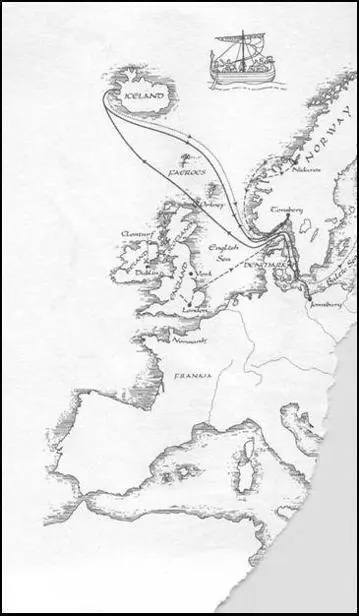

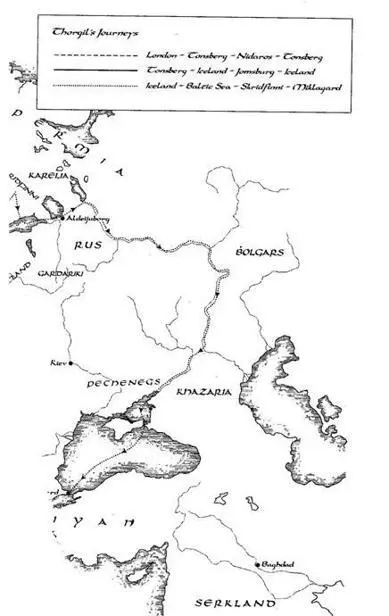

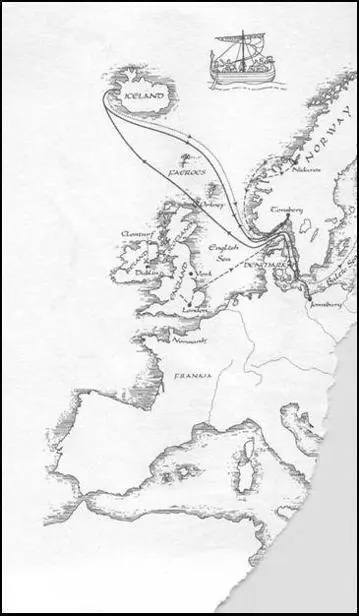

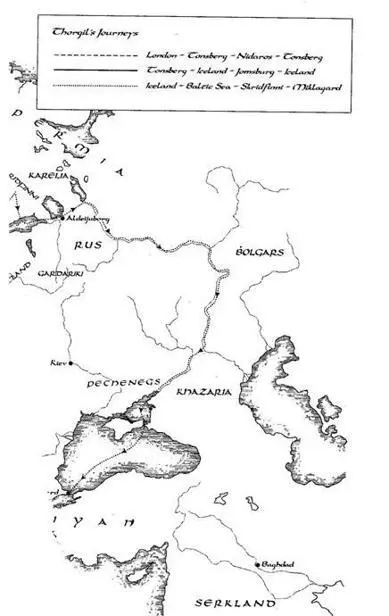

Maps

To my holy and blessed master, Abbot Ceraldus,

As requested of your unworthy servant, I send this, the second of the writings of the false monk Thangbrand. Alas, I must warn you that many times the work is even more disturbing than its antecedent. So deeply did the author's life descend into iniquity that many times I have been obliged, when reading his blasphemies, to set aside the pages that I might pray to Our Lord to cleanse my mind of such abominations and beseech Him to forgive the sinner who penned them. For here is a tale of continuing deceit and idolatry, of wantonness and wicked sin as well as violent death. Truly, the coils of deception, fraud and murder drag almost all men down to perdition.

The edges of many pages are scorched and burned by fire. From this I deduce that this Pharisee began to write his tale of depravity before be great conflagration so sadly destroyed our holy cathedral church of St Peter at York on 19 September in the year of our Lord 1069. By diligent enquiry I have learned that the holocaust revealed a secret cavity in the wall of the cathedral library, in which these writings had been concealed. A God-fearing member of our flock, making this discovery, brought the documents to my predecessor as librarian with joy, believing them to contain pious scripture. Lest further pages be discovered to dismay the unwary, I took it upon myself to visit the scene of that devastation and search the ruins. By God's mercy I found no further examples of the reprobate's writings, but with a heavy heart I observed that nothing now remains of our once-great cathedral church, neither the portico of St Gregory, nor the glass windows nor the panelled ceilings. Gone are the thirty altars. Gone too is the great altar to St Paul. So fierce was the heat of the fire that I found spatterings of once-molten tin from the bellcote roof. Even the great bell, fallen from the tower, lay misshapen and dumb. Mysterious indeed are the ways of the Lord that these profane words of the ungodly should survive such destruction.

So great is my abhorrence of what has emerged from that hidden pustule of impiety that I have been unable to complete my reading of all that was found. There remains one more bundle of documents which I have not dared to examine.

On behalf of our community, I pray for your inspired guidance and that the Almighty Lord may keep you securely in bliss. Amen.

Aethelred

Sacristan and Librarian

Written in the month of October in the Year of our Lord One thousand and seventy-one.

ONE

I lost my virginity — to a king's wife.

Few people can make such a claim, least of all when hunched over a desk in a monastery scriptorium while pretending to make a fair copy of St Luke's gospel, though in fact writing a life's chronicle. But that is how it was and I remember the scene clearly.

The two of us lay in the elegant royal bed, Aelfgifu snuggled luxuriously against me, her head resting on my shoulder, one arm flung contentedly across my ribs as if to own me. I could smell a faint perfume from the glossy sweep of dark chestnut hair which spread across my chest and cascaded down onto the pillow we shared. If Aelfgifu felt any qualms, as the woman who had just introduced a nineteen-year-old to the delights of lovemaking but who was already the wife of Knut, the most powerful ruler of the northern lands, she did not show them. She lay completely at ease, motionless. All I could feel was the faint pulse of her heart and the regular waft of her breath across my skin. I lay just as still, I neither dared to move nor wanted to. The enormity and the wonder of what had happened had yet to ebb. For the first time in my life I had experienced utter joy in the embrace of a beautiful woman. Here was a marvel which once tasted could forgotten.

The distant clang of a church bell broke into my reverie. The

sound slid through the window embrasure high in the queen's chambers and disturbed our quiet tranquillity. It was repeated, then joined by another bell and then another. Their metallic clamour reminded me where I was: London. No other city that I had visited boasted so many churches of the White Christ. They were springing up everywhere and the king was doing nothing to obstruct their construction, the king whose wife was now lying beside me, skin to skin.

The sound of the church bells made Aelfgifu stir. 'So, my little courtier,' she murmured, her voice muffled against my chest, 'you had better tell me something about yourself. My servants inform me that your name is Thorgils, but no one seems to know much about you. It's said you have come recently from Iceland. Is that correct?'

'Yes, in a way,' I replied tentatively. I paused, for I did not know how to address her. Should I call her 'my lady'? Or would that seem servile after the recent delight of our mingling, which she had encouraged with her caresses, and which had wrung from me the most intimate words? I hugged her closer and tried to combine both affection and deference in my reply, though I suspect my voice was trembling slightly.

'I arrived in London only two weeks ago. I came in the company of an Icelandic skald. He's taken me on as his pupil to learn how compose court poetry. He's hoping to find employment with . . .' Here my voice trailed away in embarrassment, for I was about to say 'the king'. Of course Aelfgifu guessed my words. She gave my ribs a little squeeze of encouragement and said, 'So that's why you were standing among my husband's skalds at the palace assembly. Go on.' She did not raise her head from my shoulder. Indeed, she pressed her body even more closely against me.

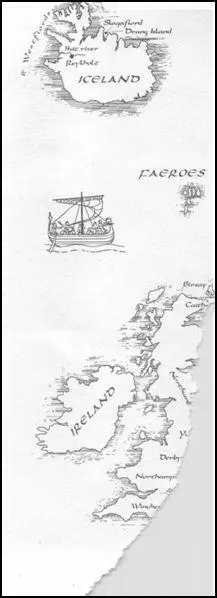

'I met the skald — his name's Herfid — last autumn on the island of Orkney off the Scottish coast, where I had been dropped off by a ship that rescued me from the sea of Ireland. It’s a complicated story, but the sailors found me in a small boat that

was sinking. They were very kind to me, and so was Herfid.' Tactfully I omitted to mention that I had been found drifting in what was hardly more than a leaky wickerwork bowl covered with cowskin, after I had been deliberately set afloat. I doubted whether Aelfgifu knew that this is a traditional punishment levied on convicted criminals by the Irish. My accusers had been monks too squeamish to spill blood. And while it was true that I had stolen their property — five decorative stones prised from a bible cover - I had only taken the baubles in an act of desperation and I felt not a shred of remorse. Certainly I did not see myself as a jewel thief. But I thought this would be a foolish revelation to make to the warm, soft woman curled up against me, particularly when the only item she was wearing was a valuable-looking necklace of silver coins.

"What about your family?' asked Aelfgifu, as if to satisfy herself on an important point.

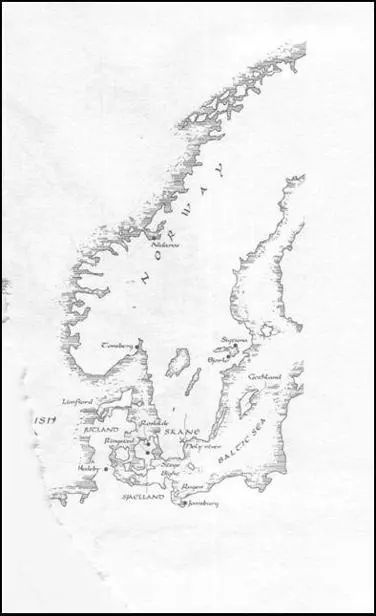

'I don't have one,' I replied. 'I never really knew my mother. She died while I was a small child. She was part Irish, I'm told, and a few years ago I travelled to Ireland to find out more about her, but I never succeeded in learning anything. Anyhow, she didn't live with my father and she had already sent me off to stay with him by the time she died. My father, Leif, owns one of the largest farms in a country called Greenland. I spent most of my childhood there and in an even more remote land called Vinland. When I was old enough to try to make my own living I had the idea of becoming a professional skald as I've always enjoyed story-telling. All the best skalds come from Iceland, so I thought I would try my luck there.'

Читать дальше