In mid-afternoon, after three hours of continuous pumping, it was time to check the water in the bilge once more. To Hector’s disappointment, the level had dropped barely an inch. Dispirited, he returned to Vlucht’s cabin and asked to borrow the chart and a pair of dividers. The Frisian captain was lying huddled in his bunk, his eyes bright with fever.

‘Will we make it?’ he whispered after watching Hector make his calculations.

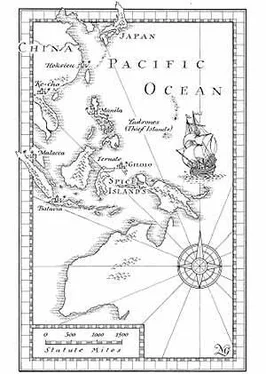

Hector put down the compasses. ‘If the wind holds fair, it could take seven or eight days to reach Tidore. I doubt we can last that long. Sooner or later the water will gain on us.’

‘Then we should abandon ship before she sinks. Head for land in the skiff, once we are close enough to the Spice Islands,’ the captain murmured.

‘But there isn’t room for all of us in the skiff,’ Hector objected.

‘Leave the worst of the invalids behind,’ wheezed Vlucht. ‘You and I both know they’ll die anyhow.’

Hector left the cabin without answering and made his way back to the main deck. What Vlucht had said about the invalids was true. With men so far advanced in the grip of scurvy, their chances of survival were slim. Yet Maria would never agree to leave the ship and abandon her patients. For that reason, if no other, Hector had made up his mind that as long as the Westflinge was afloat, he would keep her on course for Tidore.

OVER THE NEXT few days progress was achingly slow. The ship advanced at less than walking pace, heaving and wallowing sluggishly on a sea that seemed determined to hold back their progress. They kept at the pump until muscles and backs were aching, hands blistered. From time to time they formed pairs and hauled buckets up through the hatches and dumped the bilge water overboard. Jezreel spent one entire morning lugging up ballast stones and dropping them into the sea. But it made little difference. On the second day they only managed to hold their own, and during the morning of the third day the water was gaining on them perceptibly. Dan stripped off and pulled up boards at various places up and down the length of the hold and wriggled in through the gaps. He held his breath, ducked down and groped in the noxious water, feeling between the frames and among the remaining ballast, trying to locate the source of the leak. But he found nothing – no eddy or current that indicated an obvious weakness in the hull. The water appeared to be seeping in all along the seams.

It was after the last of these fruitless dives that he reappeared on deck carrying in his arms one of the wooden boxes that had been left in the hold.

‘I could do with some more kindling for the galley,’ Jacques remarked. He was scraping green mould from a piece of salt fish he’d discovered in a locker.

‘First, let’s see what’s inside,’ said Dan. Scratches and gouges showed that the box had been opened and loosely nailed back down. The Miskito took a marlin spike and levered open the lid.

‘This will make you happy, Jacques,’ he said, peering in. ‘There is a fine fat chicken nesting here in straw.’

‘All that pumping has turned your brain to soup, lourdaud,’ retorted the Frenchman.

Dan reached into the box and took out several handfuls of packing straw. He lifted out a large, rusty metal cube. On top of the cube stood an eight-inch-tall model of a hen, with four chicks at her feet. They too were covered in rust.

‘What have you there?’ Jacques demanded.

‘Some sort of clock,’ said Dan. He brushed off stray wisps of the packing material and turned the cube to show Jacques that one side was inscribed with a clock face. He felt again inside the wooden box and found the hour and minute hands, which had become detached.

‘Pity we cannot get that hen to lay. Fresh eggs would be useful,’ Jacques commented, turning back to his work, his nose wrinkled in disgust at the rank smell of the putrid fish.

Dan was examining the hen more closely. ‘The wings are hinged at the base, and the chicks are fixed to some sort of disc,’ he said. He put the clock down on the deck. ‘I wonder what it is supposed to do.’

‘Sweeten the Governor of Hoksieu and his chief of customs,’ said Vlucht. The Frisian had shuffled out of his cabin. ‘Give a Chinaman a fancy clock, and the happier he will be. They’re mad for those things. I purchased that hen-and-chickens in Batavia, and several other plain timepieces. Cost a fortune, but nearly got me flogged for insolence.’

‘What happened?’ Jacques was intrigued.

‘The device worked well enough when I bought it off a thieving Zeelander. Must have got damaged during the voyage. When I presented the clock to the Governor at a formal reception, he asked for a demonstration. Nothing happened except that it made a nasty sound like a slow fart. He took it as an insult. Did more harm than good.’

Dan opened the flap in the back of the clock and inspected the mechanism. ‘Looks as though a mainspring was dislodged.’

‘So you think you know something about clocks?’ said Vlucht scornfully.

‘Looks much the same as an old-fashioned wind-up musket lock,’ said the Miskito. ‘Do you mind if I try to make it work?’

‘You can throw it overboard for all I care,’ grumbled the Frisian and stumped away.

Tinkering with the insides of the clock was a diversion from the chore of pumping. Dan took most of a day to clean and replace the cogs and wheels, and to work out how they should mesh and turn. Jacques used his knowledge of locks and metal springs to advise, and provided dabs of rancid butter to grease the mechanism. Finally, when they were satisfied with their efforts, they invited everyone who was fit enough to climb to the poop deck at five minutes before noon, there to witness a grand inauguration of their handiwork. When their audience had gathered, Jacques held up the cleaned and polished clock to show it off. Dan wound the mechanism with a key, closed the flap and carefully positioned the two hands to show just before noon. Then Jacques placed the device on top of the helmsman’s compass box, stood back and waited.

Hector entered into the spirit of the occasion. He stepped forward with his backstaff to take his usual noonday sight. When the sun reached the zenith he called out the time. Everyone turned round and watched the clock expectantly. There was a long pause while nothing happened. Then the minute hand jerked to the vertical with an audible click. Cogs and wheels whirred internally. The four chicks began to move around in a circle at the hen’s feet. The mother hen tilted forward and half-raised her wings, only for something to go wrong. Instead of flapping, the wings stuck halfway and vibrated with a grinding noise. Then, to a general burst of laughter, the automaton let out a false, rusty cockerel’s crow. ‘Even if the device had worked in front of the Governor of Hoksieu, I doubt he’d have been very impressed,’ commented Hector to Vlucht with a smile. ‘Surely even in China, hens don’t crow.’

LATER THAT SAME afternoon the weather turned against them. The wind, which had been steadily in their favour, backed into the south-west and then rose to a half-gale with driving rain. The Westflinge lurched and shuddered on the increasingly boisterous waves. Vlucht shambled off to his bunk, leaving Hector in charge. Hector helped his comrades to hand the sails, then went with Dan to check the hold once again.

‘The vessel is working badly,’ Dan commented. Little jets of bilge water were now spurting up between the planks in the floor of the hold as the vessel rolled.

They returned to the half-deck and Hector tried moving the whipstaff. He felt the ship barely respond under his hand. With each passing hour she was becoming more of a floating hulk. ‘I don’t know how much longer she’ll stay afloat,’ he confessed.

Читать дальше