‘At least take some guns with you,’ Hector said. ‘That’s what you came for.’

‘I know that the sickness travels. I do not want to bring it back to Rota with me. You and your people can do what you want.’

‘Then ask Dan, Maria and Jacques to join me,’ said Hector. He turned to face Vlucht. ‘There are four healthy men with me, all experienced seamen.’ He was speaking hurriedly, trying to make his point before Ma’pang left with the sakman. ‘There’s also a woman, and she can nurse your invalids. If you supply these natives with muskets and powder, we will stay aboard and help bring your vessel to safe harbour.’

The Dutch captain allowed himself a cynical laugh. ‘And if I refuse, then these savages will take our guns anyway. Of course I accept your offer.’

‘Wait, Ma’pang, wait just a few minutes,’ Hector called out. He turned back towards Vlucht. ‘Quick, where’s the arms chest?’

The Dutchman pointed towards a door under the overhang of the quarterdeck. Hector beckoned to Jezreel and together they ran to find the Westflinge ’s store of guns. Moments later they had dragged the arms chest to the ship’s rail. Jezreel smashed open the lid and they began handing its contents down to the Chamorro, who nervously accepted the weapons while keeping as safe a distance as possible.

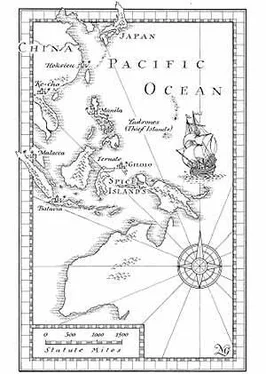

Maria and the others had scarcely set foot on the deck of the Dutch vessel before the Chamorro were casting off the lines holding the sakman alongside. They were in near-panic, handling the ropes as though fearful to touch them. They wouldn’t even reach out and fend off against the side of the merchant ship. Instead they waited for the rise and fall of the swell to drift the sakman clear. Nor was there a backward glance as the spidery shape of their vessel turned and headed back to the Thief Islands.

FIFTEEN

THE REGULAR THUMP and shudder as the Westflinge ’s steering gear slammed from side to side with each roll of the ship was grating on Hector’s nerves. ‘Do you mind if I deal with that?’ he asked the Dutch captain. Vlucht was racked with another fit of coughing and weakly waved a hand, indicating that, as far as he was concerned, Hector and his comrades could do as they liked.

Leaving Maria and the others, Hector went with Dan and Stolck to the half-deck. The helm was an old-fashioned, heavy whipstaff and it was banging back and forth. Dan picked up a short length of rope, took a turn around the tiller bar and secured it. The slamming stopped. Hector climbed on up to the quarterdeck with Stolck and walked aft to inspect the flag tangled around its staff. He unwound the cloth and let it flap in the breeze.

He had never seen the design before: three diagonal silver stripes on a dark-blue field. Stitched on the stripes were red heart-shaped symbols. He counted seven of them.

‘Whose flag is that?’ he asked Stolck.

‘Frisia – the place I come from,’ answered the Hollander. ‘Those red hearts represent the seven islands of our region. Some say there should be nine of them; others insist that they aren’t hearts, but pompebledden, leaves of water lilies.’

‘And why would Vlucht choose to fly such a flag?’

Stolck snorted. ‘Because we Frisians are pig-headed and stubborn. We like to show our independence.’

‘So Vlucht doesn’t see himself as a Hollander?’

‘Not unless it suits him. I’d say this ship is an interloper.’

Hector had come across interlopers before, in the Caribbees. Smugglers in all but name, they made surreptitious voyages to places where they had no right to be and trespassed on trading monopolies belonging to larger companies.

Stolck spat over the rail. ‘If the holy and sainted Dutch East India Company caught Vlucht in this area, the Westflinge and her cargo would be confiscated and he’d be given a stiff gaol sentence, whatever flag he was flying.’

‘Then surely there’s little advantage in sailing under false colours?’

‘It helps in foreign ports. If Captain Vlucht goes into Canton, for example, and claims he’s a Frisian ship – not Dutch – then the local merchants can do business with him directly, instead of going through the Company’s local agent and paying a commission.’

Hector looked at Stolck thoughtfully. The Hollander seemed to be remarkably well informed about interlopers and the China trade.

They made their way back to the main deck. Maria had just emerged from the forecastle, where Vlucht and his crew had been holed up. ‘Hector, we need to attend to the sick quickly,’ she said firmly. ‘You should see for yourself how ill they are.’

Hector followed her through the open door to the crew accommodation. As he stepped inside the gloomy, unlit cabin, the rancid stench of damp, sweat and vomit caught him by the throat. With its low ceiling, the forecastle was so dark that it was difficult to make out any details. There was a rough table and two benches in the centre of the room, all of them fixed to the floor. Crude bunks like stable mangers extended along the bulkheads, and sick men lay in them all. On the floor were several shapeless bundles. One of them moved slightly, and Hector realized it was a man struggling to sit up.

‘There are very sick men in here,’ Maria said. ‘They must be cared for.’

Hector made no reply. He’d recognized one reason for the smell. It was the rotting stink of scurvy, mixed with a sweetish fetid odour that he knew was the smell of dead flesh.

‘It started with Batavia fever,’ said Vlucht. He’d come into the doorway behind them, blocking out most of the already feeble light. ‘A few of the men began to complain of headaches and bone pains when we were only a couple of weeks into the voyage. That’s normal enough in these waters. Nothing to worry about.’

The invalid on the floor held out a tin cup. His arm was shaking. Hector saw that the man’s mouth was deformed by some sort of soft growth bulging from his gums. Maria took the cup and went to find water.

‘The fever did the rounds, as we expected, and soon we were accustomed to it. But the Chinese customs people used it as an excuse to send us on our way,’ Vlucht continued. ‘Quarantined the ship for a month before obliging us to leave.’ He laughed savagely. ‘Of course that was after they had impounded our cargo.’

Maria returned carrying the water and knelt down by the sick man, holding the cup to his ghastly mouth so that he could drink. Even from a yard away, Hector could smell the foul stink of his breath.

Maria rose to her feet. ‘Hector, we must get these men onshore or they’ll not live.’ He didn’t answer, but took her by the elbow and gently led her outside. Speaking softly so that no one else could hear, he said, ‘Maria, I’ll do what I can. But this ship is a near-wreck, and I have no idea how far it is to the nearest port.’

She pulled her arm from his grasp. ‘Then find out. That Dutch captain has little care for his men.’

‘I’ll check if there are any medical stores aboard,’ he assured her. ‘Jezreel can help move the sick men out on deck so that the forecastle can be cleaned up. We might even be able to fumigate it, or spread some vinegar if it’s available. But don’t expect too much. Most of the invalids are likely to die.’

She glared at him. ‘Two of the men back in there are dead already.’

‘Captain,’ Hector called out. ‘What’s the Westflinge ’s current position?’

‘I may be sick, but I can still navigate,’ said the Frisian sourly and set off at a slow shuffle towards his cabin. Hector followed him and helped spread out the chart that lay on the captain’s unmade bed.

Читать дальше