‘It seems we won’t go hungry,’ observed Jacques, bleary-eyed and scratching his close-cropped head. He must have slept badly.

A whiff of burning surprised Hector. At the foot of the mainmast, deep down in the hull and sheltered from the breeze, one of the Chamorro had struck a flint and set alight a twist of dried coconut husk. He waited until the flame was steady, then touched it to a little pile of charcoal heaped on a flat stone. He crouched over the tiny fire, blowing gently, nursing the flame until the charcoal was glowing. The newly caught fish were gutted and cleaned by his companions, then grilled one by one and distributed.

Hector returned to sit by Ma’pang and discuss the prospects for the voyage. He learned that the sakman carried enough water for ten days at sea. When that reserve was halfway exhausted, the vessel would have to turn back. He found it difficult to concentrate. His attention strayed constantly towards the little cabin. When Maria did emerge soon afterwards, she looked more relaxed than he had yet seen her. Her hair was tied back with a ribbon and she was dressed in a simple petticoat, with her arms and feet bare. Watching her as she made her way to the base of the mast and accepted a serving of the cooked fish, Hector felt thwarted and impatient. She was so close physically and yet, with everyone’s eyes upon them, he had to keep a distance.

So the day wore on. The sakman maintained its remarkable pace. The Chamorro crew took turns to steer, very occasionally adjusting the slant of the sail in response to a murmur from Kepuha. The old man sat unmoving for hour after hour, seemingly impervious to the sun and wind.

The midday meal was a ration of breadfruit washed down with a few mouthfuls of water. The breadfruit came as a mash scooped from a basket, half-fermented. Heated on the stone cooking slab, it had a slightly sour taste. By then Hector was hungry and found it delicious. Then, an hour before dusk, the wind finally failed them completely. It had been easing in strength all afternoon, and the sakman had been travelling slower and slower. Now the vessel moved at less than walking pace. The great sail hung slack, filled and then went slack again. The sakman rose and fell as a long, slow swell passed under her. Ma’pang balanced his way along one of the struts holding the outrigger and lowered himself into the sea. He stayed in the water for a good ten minutes, hanging on to the float, motionless. When he climbed back on the boat, he went immediately to Kepuha and spoke quietly to the old man.

‘What’s happening?’ Hector asked.

‘The makhana must be kept informed.’

‘Informed of what?’ asked Hector, puzzled.

‘Of the current.’

Hector looked at the big native in open disbelief. The water had not yet dried after Ma’pang’s swim. His dark skin glistened, and a few beads of water gleamed in his bushy hair.

‘You can tell what the current is doing by immersing yourself?’

‘Of course,’ Ma’pang replied as if speaking to a simpleton. ‘If you keep still, you can feel the current. The direction it goes and how strongly.’

Hector suppressed his doubts. Anything that would help Kepuha in his navigation was valuable.

‘How long do you think the calm will last?’

Ma’pang shrugged. ‘Kepuha says that the wind will come again tomorrow in mid-morning. After the full moon.’

‘And what about the patache? Does Kepuha know whether it too is delayed?’

Ma’pang shook his head. ‘We can only hope that the patache is caught in the same calm as us.’

As the sun dipped below the horizon, the sakman was completely motionless on a glassy sea. The meagre supper of leftover fish scraps and another gulp or two of water were consumed in silence. An air of patient resignation settled over the company. Everyone knew there was nothing they could do but wait for the wind to return. Even Kepuha ceased his prayers and chants. After the brief tropical dusk, a full moon rose, shining hard and bright. Hector joined Maria as she sat on an outrigger strut beside the shelter, suspended above the calm sea. Neither of them spoke. The moonbeams were so strong they penetrated several feet into the water. Looking down from their perch, Hector could see three or four fish, each as long as his arm, cruising slowly back and forth beneath the shadow of the vessel. He recognized their blade-shaped bodies and high, blunt heads. They were the same voracious creatures that hunted flying fish by day. Now they seemed relaxed and sociable, spreading their fins so that they appeared to be balancing on underwater wings of blue. The only sound was the gentle swash of water against the hull as the sakman rocked a few inches at a time.

‘Do you think we will overtake the patache?’ Maria asked softly.

‘It all depends on the wind,’ Hector answered. ‘Kepuha forecasts a good breeze tomorrow.’

‘The crew seem to respect him.’

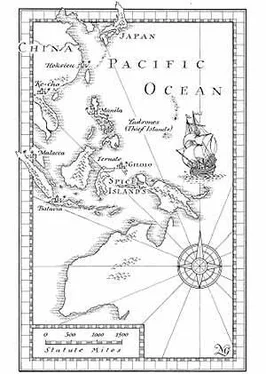

‘Ma’pang says that Kepuha is one of the greatest navigators the Chamorro have ever known.’ He looked up at the sky. Beyond the halo of the moon he could faintly detect the pinpoints of the distant stars. ‘The Chamorro believe that at the beginning of time their god-like ancestors made voyages through the heavens. They marked their passage with stars. Kepuha knows their paths and follows them. Above every island the gods left certain stars to mark their location.’

‘Does that make sense to you?’

‘It’s a different way of looking at the heavens. I measure the stars and sun to decide where I am, then use a chart and compass to plot a course to my destination. Kepuha’s system is more direct. For him, the stars are signposts in the sky.’

They sat together in companionable silence for several minutes. Then she said softly, ‘If only we had signposts.’

Hector took a deep breath. ‘To show us where to direct our lives?’

‘Yes.’

‘And if you had to select a way, where would you wish to go?’

‘Somewhere safe and calm, a place where our differences and backgrounds are of no concern to others.’

‘If such a place exists, then we’ll search for it and find it,’ he said, though he was conscious that his reply sounded a little boastful.

She seemed to accept his answer. ‘Hector, I’m so happy that we are together. I know you love me, and I have the same feeling for you.’ She hesitated before continuing. ‘But until we find that place, something will be left unfinished. I hope you can understand that.’

Hector struggled to put his thoughts into words. He knew that Maria was setting the boundaries for their relationship in the days or weeks to come. ‘I do understand, Maria, and I will be content for us to cherish one another. We’ll wait to find that place where we can be safe together.’

She turned and kissed him lightly on the mouth. ‘Hector,’ she said, ‘sometimes when I’m with you, I feel just like this, floating on a quiet expanse of calm.’ Then she moved to one side and disappeared into the little cabin.

AS KEPUHA PREDICTED, the wind came next morning. It arrived in dramatic fashion, bringing a torrential rainstorm that swept down from the north and enveloped the sakman. Visibility was reduced to a few yards, and within moments everything on the vessel was soaked. The sakman leaped forward, her waterlogged sail filling with an alarming creaking of the mast and stays. Ma’pang eased the mainsheet to reduce the pressure of the wind, and the Chamorro crew scrambled to place clay jars where they would catch the runnels of fresh water cascading off the sail. Then the vessel ran blindly through the murk.

When the rainstorm passed on, it left behind a dull, overcast sky and a sullen, lumpy sea, no longer deep blue but a dingy slate-grey. The air was still warm, but damp and clammy. Nothing dried. Hector watched to see if Kepuha would manage to set a course now that he no longer had the sun to guide him. The makhana appeared unruffled. He sat at the stern as if nothing had changed.

Читать дальше