Maria gazed out across the sunlit bay, unseeing. ‘After I refused to testify at your trial for piracy, everything changed.’

‘Were you accused of lying?’

‘Not openly. But I was ignored, almost shunned. The same Spanish officials who had brought me from Peru to London, to give evidence at your trial, treated me as though I had betrayed my country.’

Hector felt guilt rise slowly within him. ‘I’m so sorry,’ he said. ‘You made that sacrifice for me. Without you I’d have been condemned to hang.’

She looked directly into his eyes. ‘I’d do it again,’ she said. ‘But the days and months that followed passed so slowly, and I had no idea what would happen.’

‘It was the same for me,’ he said. ‘But now it will be different.’

‘From the bottom of my heart, I hope so,’ she answered. ‘Two days ago I wept, not because I was sorry to abandon Aganah and come away with you, but from relief that finally my wait was over.’

Hector felt humbled. ‘Was your life here so difficult?’

She nodded, and he noticed that her eyes were moist with tears once again. ‘When I first arrived in these islands, I told myself I’d wait two years, no more. If after that time you hadn’t come, I’d force myself to forget you. I’d make a new beginning.’

‘What did you plan to do?’

‘Ask Doña Juana to release me from service. I’m sure she would have agreed. At heart she’s a kind woman. She’d have persuaded her husband to find me passage to Manila on the next ship.’

‘Was it Don Fernando who was difficult?’

Maria bit her lips. ‘The Governor blamed me for his own troubles. He never said anything outright. But from the moment I returned to Peru, he was against me. Weeks would pass without him speaking to me directly, and I could sense his anger seething within him. And in all truth I was partly responsible for his disgrace.’

Hector allowed a long moment to pass before he touched on a subject that he knew would be a delicate one.

‘Maria,’ he said at last, ‘to leave these islands, we must have a suitable boat. The only way we can do that is to seize it from your compatriots. There will be bloodshed and—’

‘Perhaps it’s better if you don’t tell me any more,’ she interrupted.

Hector shook his head. ‘No. There mustn’t be secrets between us. Dan, Jezreel and the others will join me in an ambush. We intend to capture the patache that brings supplies to Aganah. The Chamorro will loot the vessel for weapons. We are to be given her launch for our voyage westwards.’

Maria looked at him in consternation. ‘Then we won’t leave the islands for many months,’ she said.

‘Why not?’

‘The patache has already been and gone.’

Hector thought he’d misheard. ‘But the Maestre de Campo told Jacques he was expecting more supplies, that a patache would be here at any time.’

Maria was struggling to keep her voice calm. ‘The patache did arrive, late last week. She dropped anchor off Aganah and stayed only long enough to unload, and then sailed onwards for Manila. The following day you and the others climbed in over the wall.’

Hector’s spirits sank. He’d built up his hopes, and had begun to believe he would really be sailing west with Maria. Now it was all in ruins. ‘I’ll have to tell the others. Maybe one of them will have another idea,’ he said lamely.

Just then they heard the sound of a distant musket shot. Alarmed for a moment, Hector thought the village was being attacked. Then he realized that Dan and Jezreel must already have started to train the Chamorro.

‘WE’RE TOO LATE. We’ve missed the Spanish vessel,’ he told Ma’pang bitterly as soon as he and Maria arrived back in the village. The Chamorro was standing outside his hut, deep in conversation with Kepuha. A little farther off, Dan was demonstrating to a group of Chamorro men how to knap a gun flint and install it in the doghead of the lock.

‘Did your woman tell you this?’ asked Ma’pang. He glanced at Maria, already surrounded by a cluster of children fascinated with her clothes.

‘She did. We must abandon our plan for an ambush.’

Ma’pang took the shaman by the arm and led him to one side and there was a long, animated exchange between the two men. Finally Ma’pang returned to Hector and said, ‘The council has already made its decision that we should attack the Spanish vessel. Kepuha believes it is not too late.’

Hector was taken aback. ‘But the ship left for Manila three days ago. We’d never catch her.’

Ma’pang seemed unconcerned. ‘Tell me how long you think it will take this vessel to reach Manila?’

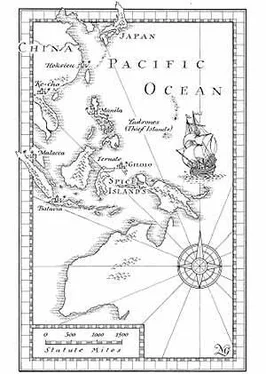

Hector made a quick calculation from what he remembered of the charts aboard the Nicholas . ‘She’s a patache, and probably sails faster than a galleon. Maybe ten days,’ he said.

‘Are you and your friends still willing to attack with muskets, if we meet up with her?’

Hector recalled a sea fight off Panama, three years earlier. On that occasion a flotilla of musketeers in canoes – including Dan, Jezreel and himself – had tackled a trio of small sailing ships armed with light cannon. The musketeers had won.

‘We are,’ he said flatly.

‘Then come with me,’ said Ma’pang. He called out to the men under Dan’s instruction, and immediately several of them ran off in the direction of the beach. Ma’pang, Hector and Kepuha followed.

They passed the place where the little fishing canoes lay drawn up on the strand, then veered to the right and a short distance farther on came to a grove of coconut palms. Set back among the trees was a barn-like building. Its palm-thatch roof was supported on stone columns similar to those that held up the uritao. It was a great cavern of a place, even larger than the bachelor house. The Chamorro stripped away the palms fronds that covered whatever was stored inside and gradually the shape of a boat emerged, similar to the fishing canoes, but much, much larger. At nearly sixty feet long, it was a substantial vessel. Like its smaller cousins, it had a long float attached to the side of the main hull by three curved, slender wooden struts. The float had been hollowed from a single large tree trunk. That was impressive enough, but Hector found it difficult to imagine what sort of giant tree had been used to provide the main hull. It stood taller than a man and was carefully shaped, with one side swelling in an elegant curve, while the other was nearly flat.

Ma’pang stood back, looking proudly at the giant canoe. ‘That is our village’s sakman,’ he said.

Hector noticed a massive pole slung from the rafter of the boat shed. ‘Is that her mast?’

Ma’pang nodded. ‘And that long bundle next to it, her sail.’

Hector stepped across to the huge canoe, and squinted down the length of the narrow blade of the hull. ‘I can see why the village takes such good care of her,’ he said wonderingly. ‘She must skim across the surface of the sea.’

Ma’pang caught the note of admiration in his remark. ‘Only a few sakman remain. The Spaniards take care to burn them if they find them. Only a handful of old men still know how to construct them. Even if we can find trees large enough.’

‘And the village council is willing to allow you to use the sakman to pursue the Spanish ship?’ Hector asked.

Ma’pang reached out and, almost lovingly, touched the sharp prow of the great boat. ‘The council agreed it would do honour to our proudest possession.’

A worrying thought struck Hector. ‘Ma’pang, what happens if we manage to overhaul the patache and take her far out to sea? How will you find your way back to Rota? I expect we’ll find charts and navigation instruments on the patache. But they will be of little use to you and, while I am willing to guide you back to Rota, I’d prefer to head on directly westwards.’

Читать дальше