Ma’pang set aside the fish head he had been sucking, and wiped his fingers on the ground. ‘You are going to tell me that we must become like Dan here.’

Hector couldn’t help but admire the way the naked warrior often seemed one step ahead of what he was about to say.

‘That’s right.’

‘And that is why he stole those muskets when we were in the fort?’

‘Yes, with enough powder and shot and those muskets, your people—’ he began.

‘A handful of muskets is not enough. The guirragos have many guns and cannon.’ Ma’pang broke off a fishbone and began to use it to pick at his sharpened teeth.

Hector ploughed on. ‘Even half a dozen muskets have their uses. Your people must first learn how to use guns. Dan and Jezreel can show them how to load and aim, how to fit new flints and keep such weapons in good repair.’

‘And after that?’

‘You obtain more muskets, distribute them to all your warriors and to any Chamorro clans who are your allies.’

‘And where do we find these extra guns?’ Ma’pang was watching Hector narrowly, a gleam of real interest in the deep-set brown eyes.

Hector drew a deep breath. This was something he and Dan had discussed during the journey back from Aganah. It was their chance to leave the islands.

‘Do you remember what I said to you on the day you captured us on the beach?’

‘That you had been set ashore to make an alliance with us. With our help you would seize the big ship that comes here yearly to supply the guirragos.’

‘Exactly. The muskets we already have are sufficient to carry out that attack ourselves, using exactly the same plan.’

‘Go on.’ Ma’pang flicked the fishbone into the embers of the cooking fire.

‘Your people paddle out to the ship, pretending to want to trade. Dan, Jezreel, Jacques and I will lie hidden in the canoes. Stolck can bring his musket. After the initial shock of our gunfire, your warriors can climb aboard and seize the ship.’

Ma’pang belched softly. ‘Five of you will not be enough. The ship is too big, too many men on board.’

‘But we don’t ambush the big galleon. Instead we seize the much smaller one, which, according to Jacques, is due very soon. She carries enough weapons to arm everyone in your village.’

The Chamorro warrior lifted his chin as he stared down at Hector. ‘And what would you want from us in exchange?’

‘Every guirrago ship brings a smaller boat that we call a launch. It is either stowed on deck or towed behind her. We ask that the Chamorro give us that boat and enough water and food to last three weeks, and allow us to leave Rota.’

‘And where would you go?’

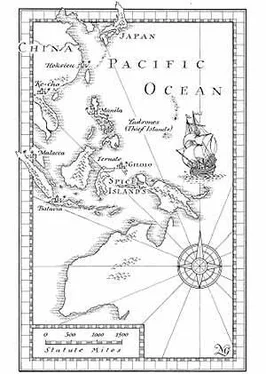

‘Towards the setting sun, because that is downwind. Eventually we will reach a place where we can contact our own people.’

Ma’pang’s red lips gleamed wetly as he spat out a shred of food. ‘I will explain your plan to the council of the old men. It is up to them to decide. But I warn you. If the plan succeeds, you will have a long, long voyage. We call our islands tano’ tasi – “land of the sea” – because we are so far from any other country.’

SEVERAL DRUNKEN Chamorro were snoring on the ground by the time the feast ended some hours later, and Hector had lost sight of Maria. He supposed she’d gone back to Ma’pang’s hut with his wife and, as it was getting dark, he decided it would be more appropriate if he spent the night in the uritao. But he got little rest. He lay awake, turning over and over in his mind what he should say to Maria.

Shortly after dawn the next day he climbed down from the bachelor house and succeeded in making a pack of bright-eyed, giggling Chamorro children understand that he wanted to find the guirrago woman. They led him to one of the larger huts at the far end of the village. As he arrived, Maria had just emerged. She’d washed and changed, and combed out her hair so that it hung loose around her shoulders. Barefoot, she wore the same plain brown skirt as the previous day and had put on a fresh, dark-blue bodice that she must have carried in her bundle of clothes. Hector thought she looked strained, and was not entirely recovered from the hectic events of the previous two days.

‘Let’s walk down to the beach,’ he proposed. He felt self-conscious and awkward. ‘The village fishing fleet makes quite a sight.’

She treated him to a guarded smile. ‘I’d like that. All the time I was in the fort, I never saw how the local people really lived.’

In silence they strolled along the track to the beach. The path wound its way through a ravine where ferns and creepers grew among tangled roots of wild banyan. They startled a bird, a native dove with an iridescent green body and a rose-coloured head, which had been feeding on fallen seeds. It flew up with a sudden clatter of wings and they stopped and watched it weave its way among the branches. Hector stepped aside and broke off a bright-yellow blossom from a small, shrubby tree.

‘Dan tells me the Chamorro use the fibres from this tree to make their fishing lines and nets,’ he explained, as he held out the flower to Maria.

She took the blossom from him and looked at it for a moment. ‘The same flowers grew around the fort in Aganah. I love their bright colours, but there’s something sad about them. Each flower lasts no more than a day. By night the petals have faded and begun to fall.’

They emerged on to the open beach. The day was hot and sunny, but a few clouds were building up on the far horizon. The Chamorro fishing fleet had been at sea since dawn and was spread across the glittering surface of the bay. For some minutes they stood and watched the youngsters fishing with hook and line from their miniature dugout canoes. Farther out, the larger boats were tacking back and forth under sail.

‘Let’s find somewhere to sit down,’ suggested Hector, and together they walked to where a fishing canoe lay drawn up on the sand, covered with palm fronds to protect it from the sun. Hector watched Maria reach out and run a finger along the red and white lines that decorated the hull. He knew she was waiting for him to begin. Yet, in his uncertainty, he did not know how to start.

‘It must feel strange for you to be among these people,’ he ventured.

‘Not really,’ she replied. ‘It’s similar to the village where I grew up. We had the same concerns – tending the crops, providing for our families, teaching the children. The people here are more fortunate in one way. They don’t fear the winter cold.’

‘Have you heard from your family?’ he asked. He knew she came from a village in Andalusia and that her parents were plain, unpretentious people. They’d encouraged their only daughter to take up a position as companion to the wife of Don Fernando at a time when he was an up-and-coming government official in Peru with a bright future ahead of him.

Her poise weakened a little. ‘I haven’t had a letter in all the time I’ve been here. In her last letter my mother wrote to say my father was in poor health. His chest was weak and he had difficulty in breathing. I don’t know if he still lives.’

As if making up her mind about something, she turned to look at him directly.

‘Hector,’ she said firmly, ‘I know you’re worried about me, and my decision to come away with you. Does it help if I tell you I had already resolved to leave Aganah?’

‘Even if I hadn’t come?’

She nodded. ‘My life here has not been good.’

Hector sensed she was holding something back. ‘Because of me?’

‘Not in the way you’re thinking. Of course, I was longing and hoping to see you again.’

‘Can you tell me what happened?’

Читать дальше