Bill Bryson - At Home

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bill Bryson - At Home» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:At Home

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

At Home: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «At Home»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

At Home — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «At Home», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Life appears to have been pretty good for the Skara Brae residents. They had jewelry and pottery. They grew wheat and barley, and enjoyed bounteous harvests of shellfish and fish, including a codfish that weighed seventy-five pounds. They kept cattle, sheep, pigs, and dogs. The one thing they lacked was wood. They burned seaweed for warmth, and seaweed makes a most reluctant fuel, but that chronic challenge for them was good news for us. Had they been able to build their houses of wood, nothing would remain of them and Skara Brae would have gone forever unimagined.

It is impossible to overstate Skara Brae’s rarity and value. Prehistoric Europe was a largely empty place. As few as two thousand people may have lived in the whole of the British Isles fifteen thousand years ago. By the time of Skara Brae, the number had risen to perhaps twenty thousand, but that is still just one person per three thousand acres, so to come across any sign of Neolithic life is always an excitement. It would have been pretty exciting even then.

Skara Brae offered some oddities, too. One dwelling, standing slightly apart from the others, could be bolted only from the outside, indicating that anyone within was being confined, which rather mars the impression of a society of universal serenity. Why it was necessary to detain someone in such a small community is obviously a question that cannot be answered over such a distance of time. Also slightly mystifying are the water-tight storage containers found in each dwelling. The common explanation is that these were used to hold limpets, a hard-shelled mollusk that abounds in the vicinity, but why anyone would want a stock of fresh limpets near at hand is a question not easy to answer even with the luxury of conjecture, for limpets are a terrible food, providing only about one calorie apiece and so rubbery as to be practically inedible anyway; they actually take more energy to chew than they return in the form of nutrition.

We don’t know anything at all about these people—where they came from, what language they spoke, what led them to settle on such a lonesome outpost on the treeless edge of Europe—but from all the evidence it appears that Skara Brae enjoyed six hundred years of uninterrupted comfort and tranquillity. Then one day in about 2500 BC the occupants vanished—quite suddenly, it seems. In the passageway outside one dwelling ornamental beads, almost certainly precious to the owner, were found scattered, suggesting that a necklace had broken and the owner had been too panicked or harried to retrieve them. Why Skara Brae’s happy idyll came to a sudden end is, like so much else, impossible to say.

Remarkably, after Skara Brae’s discovery more than three quarters of a century passed before anyone got around to having a good look at it. William Watt, from nearby Skaill House, salvaged a few items; more horrifyingly, a later house party, armed with spades and other implements, emerged from Skaill House and cheerfully plundered the site one weekend in 1913, taking away goodness knows what as souvenirs, but that was about all the attention Skara Brae attracted. Then in 1924 another storm swept a section of one of the houses into the sea, after which it was decided that the site should be formally examined and made secure. The job fell to an interestingly odd but brilliant Australian-born Marxist professor from the University of Edinburgh who loathed fieldwork and didn’t really like going outside at all if he could possibly help it. His name was Vere Gordon Childe.

Childe wasn’t a trained archaeologist. Few people in the early 1920s were. He had read classics and philology at the University of Sydney, where he had also developed a deep and abiding attachment to communism, a passion that blinded him to the excesses of Joseph Stalin but colored his archaeology in interesting and surprisingly productive ways. In 1914, he came to the University of Oxford as a graduate student, and there he began the reading and thinking that led to his becoming the foremost authority of his day on the lives and movements of early peoples. In 1927, the University of Edinburgh appointed him to the brand-new post of Abercrombie Professor of Prehistoric Archaeology. This made him the only academic archaeologist in Scotland, so when something like Skara Brae needed investigating the call went out to him. Thus it was in the summer of 1927 that Childe traveled north by train and boat to Orkney.

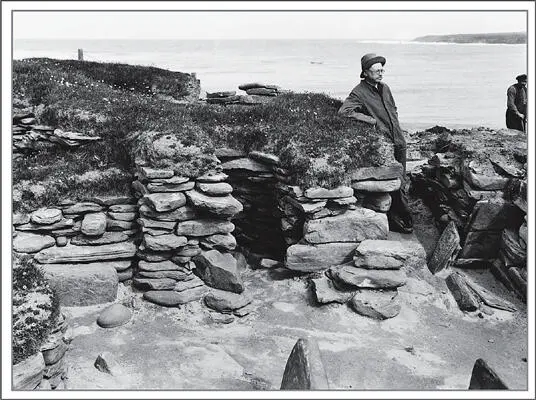

Vere Gordon Childe at Skara Brae, 1930 (photo credit 2.1)

Nearly every written description of Childe dwells almost lovingly on his oddness of manner and peculiar looks. His colleague Max Mallowan (now best remembered, when remembered at all, as the second husband of Agatha Christie) said he had a face “so ugly that it was painful to look at.” Another colleague recalled Childe as “tall, ungainly and ugly, eccentric in dress and often abrupt in manner [with a] curious and often alarming persona.” The few surviving photographs of Childe certainly confirm that he was no beauty—he was skinny and chinless, with squinting eyes behind owlish spectacles, and a mustache that looked as if it might at any moment stir to life and crawl away—but whatever unkind things people might say about the outside of his head, the inside was a place of golden splendor. Childe had a magnificent, retentive mind and an exceptional facility for languages. He could read at least a dozen, living and dead, which allowed him to scour texts both ancient and modern on any subject that interested him, and there was hardly a subject that didn’t. The combination of weird looks, mumbling diffidence, physical awkwardness, and intensely overpowering intellect was more than many people could take. One student recalled how in a single ostensibly sociable evening Childe had addressed those present in half a dozen languages, demonstrated how to do long division in Roman numerals, expounded critically upon the chemical basis of Bronze Age datings, and quoted lengthily from memory from a range of literary classics. Most people simply found him exhausting.

He wasn’t a born excavator, to put it mildly. A colleague, Stuart Piggott, noted almost with awe Childe’s “inability to appreciate the nature of archaeological evidence in the field, and the processes involved in its recovery, recognition and interpretation.” Nearly all his many books were based on reading rather than personal experience. Even his command of languages was only partial: although he could read them flawlessly, he used his own made-up pronunciations, which no one who spoke the languages could actually understand. In Norway, hoping to impress colleagues, he once tried to order a dish of raspberries and was brought twelve beers.

Whatever his shortcomings of appearance and manner, he was unquestionably a force for good in archaeology. Over the course of three and a half decades he produced six hundred articles and books, popular as well as academic, including the best sellers Man Makes Himself (1936) and What Happened in History (1942), which many later archaeologists said inspired them to take up the profession. Above all he was an original thinker, and at just the time that he was excavating at Skara Brae he had what was perhaps the single biggest and most original idea of twentieth-century archaeology.

The human past is traditionally divided into three very unequal epochs—the Paleolithic (or Old Stone Age), which ran from 2.5 million years ago to about 10,000 years ago; the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age), covering the period of transition from hunter-gathering lifestyles to the widespread emergence of agriculture, from 10,000 to 6,000 years ago; and the Neolithic (New Stone Age), which covers the closing but extremely productive 2,000 years or so of prehistory, up to the Bronze Age. Within each of these periods are many further subperiods—Olduwan, Mousterian, Gravettian, and so on—that are mostly of concern to specialists and needn’t distract us here.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «At Home»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «At Home» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «At Home» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.