Bill Bryson - At Home

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bill Bryson - At Home» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:At Home

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

At Home: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «At Home»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

At Home — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «At Home», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The arrival of the dining room marked a change not only in where the food was served but also in how it was eaten and when. For one thing, forks were now suddenly becoming common. Forks had been around for a long time but took forever to gain acceptance. Fork originally signified an agricultural implement and nothing more; it didn’t take on a food sense until the mid-fifteenth century, and then it described a large implement used to pin down a bird or joint for carving. The person credited with introducing the eating fork to England was Thomas Coryate, an author and traveler from the time of Shakespeare who was famous for walking huge distances—including once to India. In 1611, he produced his magnum opus, Coryate’s Crudities , in which he gave much praise to the dinner fork, which he had first encountered in Italy. The same book was also notable for introducing English readers to the Swiss folk hero William Tell and to a new device called the umbrella.

Eating forks were thought comically dainty and unmanly—and dangerous, too, come to that. Since they had only two sharp tines, the scope for spearing one’s lip or tongue was great, particularly if one’s aim was impaired by wine and jollity. Manufacturers experimented with additional numbers of tines—sometimes as many as six—before settling, late in the nineteenth century, on four as the number that people seemed to be most comfortable with. Why four should induce the optimum sense of security isn’t easy to say, but it does seem to be a fundamental fact of flatware psychology.

The nineteenth century also marked a time of change for the way food was served. Before the 1850s, nearly all the dishes of the meal were placed on the table at the outset. Guests would arrive to find the food waiting. They would help themselves to whatever was nearby and ask for other dishes to be passed or call a servant over to fetch one for them. This style of dining was known as service à la française , but now a new practice came in known as service à la russe in which food was delivered to the table in courses. A lot of people hated the new practice because it meant everyone had to eat everything in the same order and at the same pace. If one person was slow, it held up the next course for everyone else, and meant that food lost heat. Dinners now sometimes dragged on for hours, putting a severe strain on many people’s sobriety and nearly everyone’s bladders.

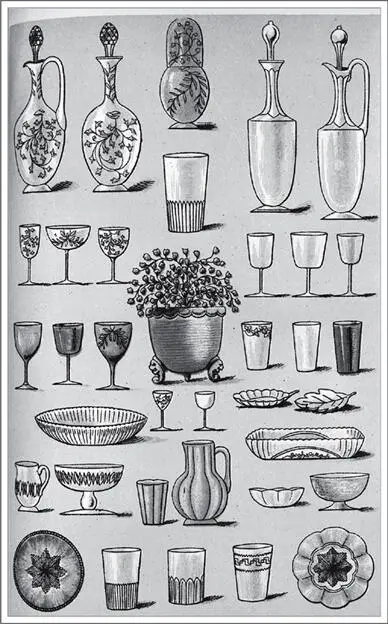

The nineteenth century also became the age of the overdressed dining table. A diner at a formal gathering might sit down to as many as nine wineglasses just for the main courses—more were brought for dessert—and a blinding array of silverware with which to conduct an assault on the many dishes put before him. The types of specialized eating implements for cutting, serving, probing, winkling, and otherwise getting viands from serving dish to plate and from plate to mouth became almost numberless. As well as a generous array of more or less conventional knives, forks, and spoons, the diner needed also to know how to recognize and manipulate specialized cheese scoops, olive spoons, terrapin forks, oyster prongs, chocolate muddlers, gelatin knives, tomato servers, and tongs of every size and degree of springiness. At one point, a single manufacturer offered no fewer than 146 different types of flatware for the table. Curiously, among the few survivors from this culinary onslaught is one that is most difficult to understand: the fish knife. Though it remains the standard instrument for dealing with fish of all kinds, no one has ever identified a single advantage conferred by its odd scalloped shape or worked out the original thinking behind it. There isn’t a single kind of fish that it cuts better or bones more delicately than a conventional knife does.

Dining was, as one book of the period phrased it, “the great trial,” with rules “so numerous and so minute in respect of detail that they require the most careful study; and the worst of it is that none of them can be violated without exposing the offender to instant detection.” Protocol ruled every action. If you wished to take a sip of wine, you needed to find someone to drink with you. As one foreign visitor explained it in a letter home: “A messenger is often sent from one end of the table to the other to announce to Mr B——that Mr A——wishes to take wine with him; whereupon each, sometimes with considerable trouble, catches the other’s eye.… When you raise your glass, you look fixedly at the one with whom you are drinking, bow your head, and then drink with great gravity.”

The overdressed dining table: table glass, including decanters, claret jugs, and a carafe, from Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management (photo credit 8.1)

Some people needed more help with the rules of table behavior than others. John Jacob Astor, one of the richest men in America but not evidently the most cultivated, astounded his hosts at one dinner party by leaning over and wiping his hands on the dress of the lady sitting next to him. One popular American guidebook, The Laws of Etiquette; or, Short Rules and Reflections for Conduct in Society , informed readers that they “may wipe their lips on the table cloth, but not blow their noses with it.” Another solemnly reminded readers that it was not polite in refined circles to smell a piece of meat while it was on one’s fork. It also explained, “The ordinary custom among well-bred persons is as follows: soup is taken with a spoon.”

Mealtimes moved around, too, until there was scarcely an hour of the day that wasn’t an important time to eat for somebody. Dining hours were dictated to some extent by the onerous and often preposterous obligations of making and returning social calls. The convention was to drop in on others between twelve and three each day. If someone called and left a card while you were out, etiquette dictated that you must return the call the next day. Not to do so was the gravest affront. What this meant in practice was that most people spent their afternoons dashing around trying to catch up with people who were dashing around in a similarly unproductive manner trying to catch up with them.

Partly for this reason the dinner hour moved later and later—from midday to midafternoon to early evening—though the new conventions were by no means taken up uniformly. One visitor to London in 1773 noted that in a single week he was invited to dinners that started successively at one, five, three, and “half after six, dinner on table at seven.” Eighty years later, when the art critic and writer John Ruskin informed his parents that it had become his habit to dine at six in the evening, they received the news as if it marked the most dissolute recklessness. Eating so late, his mother told him, was dangerously unhealthy.

Another factor that materially influenced dining times was theater hours. In Shakespeare’s day performances began about two o’clock, which kept them conveniently out of the way of mealtimes, but that was dictated largely by the need for daylight in open-air arenas like the Globe. Once plays moved indoors, starting times tended to get later and later and theatergoers found it necessary to adjust their dining times accordingly—though this was done with a certain reluctance and even resentment. Eventually, unable or unwilling to modify their personal habits any further, the beau monde stopped trying to get to the theater for the first act and took to sending a servant to hold their seats for them till they had finished dining. Generally they would show up—noisy, drunk, and disinclined to focus—for the later acts. For a generation or so it was usual for a theatrical company to perform the first half of a play to an auditorium full of dozing servants who had no attachment to the proceedings and to perform the second half to a crowd of ill-mannered inebriates who had no idea what was going on.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «At Home»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «At Home» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «At Home» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.