Bill Bryson - At Home

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bill Bryson - At Home» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:At Home

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

At Home: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «At Home»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

At Home — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «At Home», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In Devon, the Reverend Jack Russell bred the terrier that shares his name, while in Oxford the Reverend William Buckland wrote the first scientific description of dinosaurs and, not incidentally, became the world’s leading authority on coprolites—fossilized feces. Thomas Robert Malthus, in Surrey, wrote An Essay on the Principle of Population (which, as you will recall from your schooldays, suggested that increases in food supply could never keep up with population growth for mathematical reasons), and so started the discipline of political economy. The Reverend William Greenwell of Durham was a founding father of modern archaeology, though he is better remembered among anglers as the inventor of “Greenwell’s glory,” the most beloved of trout flies.

In Dorset, the perkily named Octavius Pickard-Cambridge became the world’s leading authority on spiders, while his contemporary the Reverend William Shepherd wrote a history of dirty jokes. John Clayton of Yorkshire gave the first practical demonstration of gas lighting. The Reverend George Garrett, of Manchester, invented the submarine.* Adam Buddle, a botanist vicar in Essex, was the eponymous inspiration for the flowering buddleia. The Reverend John Mackenzie Bacon of Berkshire was a pioneering hot-air balloonist and the father of aerial photography. Sabine Baring-Gould wrote the hymn “Onward, Christian Soldiers” and, more unexpectedly, the first novel to feature a werewolf. The Reverend Robert Stephen Hawker of Cornwall wrote poetry of distinction and was much admired by Longfellow and Tennyson, though he slightly alarmed his parishioners by wearing a pink fez and passing much of his life under the powerfully serene influence of opium.

Gilbert White, in the Western Weald of Hampshire, became the most esteemed naturalist of his day and wrote the luminous and still much loved Natural History of Selborne . In Northamptonshire, the Reverend M. J. Berkeley became the foremost authority on fungi and plant diseases; less happily, he appears to have been responsible for the spread of many injurious diseases, including the most pernicious of all domestic horticultural blights, powdery mildew. John Michell, a rector in Derbyshire, taught William Herschel how to build a telescope, which Herschel then used to discover Uranus. Michell also devised a method for weighing the Earth, which was arguably the most ingenious practical scientific experiment in the whole of the eighteenth century. He died before it could be carried out, and the experiment was eventually completed in London by Henry Cavendish, a brilliant kinsman of Paxton’s employer the Duke of Devonshire.

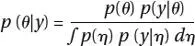

Perhaps the most extraordinary clergyman of all was the Reverend Thomas Bayes, from Tunbridge Wells in Kent, who lived from about 1701 to 1761. Bayes was by all accounts a shy and hopeless preacher, but a singularly gifted mathematician. He devised the mathematical equation that has come to be known as Bayes’s theorem and that looks like this:

People who understand Bayes’s theorem can use it to work out complex problems involving probability distributions—or inverse probabilities, as they are sometimes called. It is a way of arriving at statistically reliable probabilities based on partial information. The most remarkable feature of Bayes’s theorem is that it had no practical applications without computers to do the necessary calculations, so in Bayes’s own day it was an interesting but fundamentally pointless exercise. Bayes evidently thought so little of his theorem that he didn’t bother to make it public. In 1763, two years after Bayes’s death, a friend sent it to the Royal Society in London, where it was published in the society’s Philosophical Transactions with the modest title of “An Essay Towards Solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances.” In fact, it was a milestone in the history of mathematics. Today Bayes’s theorem is used in modeling climate change, predicting the behavior of stock markets, fixing radiocarbon dates, interpreting cosmological events, and doing much else where the interpretation of probabilities is an issue—and all because of the thoughtful jottings of an eighteenth-century English clergyman.

A great many other clergymen didn’t produce great works but rather great children. John Dryden, Christopher Wren, Robert Hooke, Thomas Hobbes, Oliver Goldsmith, Jane Austen, Joshua Reynolds, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Horatio Nelson, the Brontë sisters, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Cecil Rhodes, and Lewis Carroll (who was himself ordained, though he never practiced) were all the offspring of parsons. Something of the disproportionate influence of the clergy can be found by doing a word search of the electronic version of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography . Enter rector and you get nearly 4,600 promptings; vicar yields 3,300 more. This compares with a decidedly more modest 338 for physicist , 492 for economist , 639 for inventor , and 741 for scientist . (Interestingly, these are not greatly larger than the number of entries called forth by entering the words philanderer, murderer , or insane , and are considerably outdistanced by eccentric , with 1,010 entries.)

There was so much distinction among clergymen that it is easy to forget that such people were in fact unusual, and that most were more like our own Mr. Marsham, who if he had any achievements at all, or indeed any ambitions, left no trace of them. His closest link to fame was that his great-grandfather, Robert Marsham, was the inventor of phenology, the science (if it is not too much to call it that) of the relation between climate and periodic biological events—the first buds on trees, the first cuckoo of spring, and so on. You might think that that was something people would keep track of anyway, but in fact no one had, at least not systematically, and under Marsham’s influence it became a wildly popular and highly regarded pastime around the world. In America, Thomas Jefferson was a devoted follower. Even as president he found time to note the first and last appearances of thirty-seven types of fruit and vegetables in Washington markets, and had his agent at Monticello make similar observations there to see if the dates betrayed any significant climatological differences between the two places. When modern climatologists say that apple blossoms of spring are appearing three weeks earlier than formerly, and that sort of thing, often it is Robert Marsham’s records they are using as source material. This Marsham was also one of the wealthiest landowners in East Anglia, with a big estate in the curiously named village of Stratton Strawless, near Norwich, where Thomas John Gordon Marsham was born in 1822 and passed most of his life before traveling the twelve miles or so to take up the post of rector in our village.

We know almost nothing about Thomas Marsham’s life there, but by chance we do know a great deal about the daily life of country parsons in the great age of country parsons thanks to the writings of one who lived in the nearby parish of Weston Longville, five miles across the fields to the north (and just visible from the roof of our rectory). He was the Reverend James Woodforde and he preceded Marsham by fifty years, but life wouldn’t have changed that much. Woodforde was not notably devoted or learned or gifted, but he enjoyed life and for forty-five years kept a lively diary that provides an unusually detailed insight into the life of a country clergyman. Forgotten for 120 years, the diary was rediscovered and published in condensed form in 1924 as The Diary of a Country Parson . It became an international best seller, even though it was, as one critic noted, “little more than a chronicle of gluttony.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «At Home»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «At Home» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «At Home» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.