Bill Bryson - At Home

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bill Bryson - At Home» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:At Home

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

At Home: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «At Home»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

At Home — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «At Home», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Even slenderer people routinely sat down to quantities of food that seem impossibly munificent, if not positively destabilizing. A breakfast recorded by the Duke of Wellington consisted of “two pigeons and three beef-steaks, three parts of a bottle of Mozelle, a glass of champagne, two glasses of port and a glass of brandy”—and this was when he was feeling a little under the weather. The Reverend Sydney Smith, though a man of the cloth, caught the spirit of the age by declining ever to say grace. “With the ravenous orgasm upon you, it seems impertinent to interpose a religious sentiment,” he explained. “It is a confusion of purpose to mutter out praises from a mouth that waters.”

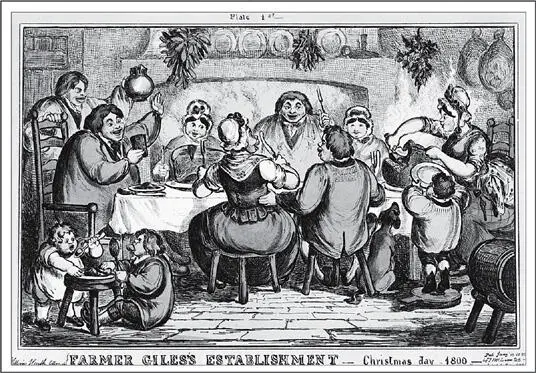

The golden age of gluttony (photo credit 4.1)

By the middle of the nineteenth century, gargantuan portions had become institutionalized and routine. Mrs. Beeton gives the following as a menu for a small dinner party: mock turtle soup; fillets of turbot in cream; fried sole with anchovy sauce; rabbits; veal; stewed rump of beef; roasted fowls; boiled ham; a platter of roasted pigeons or larks; and, to finish, rhubarb tartlets, meringues, clear jelly, cream, rice pudding, and soufflé. This was, in Mrs. Beeton’s book, food for six people.

The ironic aspect was that the more attention the Victorians devoted to food, the less comfortable with it they seemed to be. Mrs. Beeton didn’t actually appear to like food at all and treated it, as she treated most things, as a kind of grim necessity to be dealt with swiftly and decisively. She was especially suspicious of anything that added zest to food. Garlic she abhorred. Chilies were barely worth mentioning. Even black pepper was only for the foolhardy: “It should never be forgotten,” she warned her readers, “that, even in small quantities, it produces detrimental effects on inflammatory constitutions.” These alarmed sentiments were echoed endlessly in books and periodicals throughout the age.

Eventually many Victorian households gave up on flavor altogether and just concentrated on trying to get food to the table hot. In larger homes that was ambition enough because kitchens could be wondrously distant from dining rooms. Audley End in Essex set something of a record in this respect by having the kitchen and dining room more than two hundred yards apart. To try to speed things up at Tatton Park in Cheshire, an internal railway line was laid down so that trolleys could be rushed from the kitchen to a distant dumbwaiter, there to be hastily dispatched onward. Sir Arthur Middleton of Belsay Hall near Newcastle became so obsessed with the temperature of the food sent to his table that he plunged a thermometer into each arriving dish and sent back for a further blast of heat, sometimes repeatedly, any that failed to register to his expected standards, so that many of his dinners were taken very late and in a more or less carbonized condition. Auguste Escoffier, the great French chef at the Savoy Hotel in London, earned the esteem of British diners not just by producing very good food, but also by employing a brigade system in the kitchens with different cooks concentrating on different foods—one for meats, one for vegetables, and so on—so that everything could be deposited on the plate at once and brought to the table in unaccustomedly steamy glory.

All this is of course at striking variance with what was said earlier about the poverty of the average person’s diet in the nineteenth century. The fact is, there is such a confusion of evidence that it is impossible to know how well or not people ate.

If average consumption is any guide, then people ate quite a lot of healthy food: almost 8 pounds of pears per person in 1851, compared with just 3 pounds now; almost 9 pounds of grapes and other soft fruits, roughly double the amount eaten now; and just under 18 pounds of dried fruit, as against 3.5 pounds today. For vegetables the figures are even more striking. The average Londoner in 1851 ate 31.8 pounds of onions, as against 13.2 pounds today; consumed over 40 pounds of turnips and rutabagas, compared with 2.3 pounds today; and packed away almost 70 pounds of cabbages per year, as against 21 pounds now. Sugar consumption was about 30 pounds a head—less than a third the amount consumed today. So on the whole it seems that people ate pretty healthily.

Yet most anecdotal accounts, written then and subsequently, indicate the very opposite. Henry Mayhew, in his classic London Labour and the London Poor , published in the year our rectory was built, suggested that a piece of bread and an onion constituted a typical dinner for a laborer, while a much more recent (and deservedly much praised) history, Consuming Passions by Judith Flanders, states that “the staple diet of the working classes and much of the lower middle classes in the mid-nineteenth century consisted of bread or potatoes, a little bit of butter, cheese or bacon, tea with sugar.”

What is certainly true is that people who had no control over their diets often ate very poorly indeed. A magistrate’s report of conditions at a factory in northern England in 1810 revealed that apprentices were kept at their machines from 5:50 in the morning to 9:10 or 9:15 at night, with a single short break for dinner. “They have Water Porridge for Breakfast and Supper”—taken at their machines—“and generally Oatcake and Treacle, or Oatcake and poor Broth, for Dinner,” he wrote. That was, almost certainly, pretty typical fare for anyone stuck in a factory, a prison, an orphanage, or some other powerless situation.

It is also true that diets were remarkably unvaried for many poorer people. In Scotland, farm laborers in the early 1800s received an average ration of 17.5 pounds of oatmeal a week, plus a little milk, and almost nothing else, though they generally considered themselves lucky because at least they didn’t have to eat potatoes. These were widely disdained for the first 150 years or so after their introduction to Europe. Many people considered the potato an unwholesome vegetable because its edible parts grew belowground rather than reaching nobly for the sun. Clergymen sometimes preached against the potato on the grounds that it nowhere appears in the Bible.

Only the Irish couldn’t afford to be so particular. For them, the potato was a godsend because of its very high yields. A single acre of stony soil could support a family of six if they were prepared to eat a lot of potatoes, and the Irish, of necessity, were. By 1780, 90 percent of people in Ireland were dependent for their survival exclusively or almost exclusively on potatoes. Unfortunately, the potato is also one of the most vulnerable of vegetables, susceptible to more than 260 types of blight or infestation. From the moment of the potato’s introduction to Europe, failed harvests became regular. In the 120 years leading up to the great famine, the potato crop failed no fewer than twenty-four times. Three hundred thousand people died in a single failure in 1739. But that appalling total was made to seem insignificant by the scale of death and suffering in 1845–46.

It happened very quickly. The crops looked fine until August 1845, and then suddenly they drooped and shriveled. The tubers when dug up were spongy and already putrefying. That year half the Irish crop was lost. The following year virtually all of it was wiped out. The culprit was a fungus called Phytophthora infestans , but people didn’t know that. Instead they blamed almost anything else they could think of—steam from steam trains, the electricity from telegraph signals, the new guano fertilizers that were just becoming popular. It wasn’t just in Ireland that the crop failed—in fact, it failed across Europe—but the Irish were especially dependent on the potato.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «At Home»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «At Home» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «At Home» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.