Bill Bryson - At Home

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bill Bryson - At Home» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:At Home

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

At Home: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «At Home»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

At Home — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «At Home», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Even something as peerless as Stonehenge was astoundingly insecure. Visitors commonly carved their names in the stones or chipped off pieces to take away as souvenirs. One man was found banging away on a sarsen with a sledgehammer. In 1883, the London and South-Western Railway announced plans to run a line through the heart of the Stonehenge site. When people complained, a railway official countered that Stonehenge was “entirely out of repair, and not the slightest use to anyone now.”

Clearly, Britain’s ancient heritage needed a savior. Enter one of the most extraordinary fellows of that extraordinary age. His name was John Lubbock, and it is remarkable that he is not better known. It would be hard to name any figure who did more useful things in more fields and won less lasting fame for it.

The son of a wealthy banker, Lubbock grew up as a neighbor of Charles Darwin in Kent. He played with Darwin’s children and was constantly in and out of the Darwin house. He had a gift for natural history, which endeared him to the great man. The two spent many hours together in Darwin’s study looking at specimens in matching microscopes. At one point when Darwin was depressed, young Lubbock was the only visitor he would receive.

Upon reaching adulthood, Lubbock followed his father into banking, but his heart was in science. He was a tireless, if slightly eccentric, experimenter. Once he spent three months trying to teach his dog to read. Developing an interest in archaeology, he learned Danish because Denmark was then the world leader in the field. His particular interest in insects led him to keep a colony of bees in his sitting room, the better to study their habits. In 1886, he discovered the pauropods—one of the family of tiny, and previously unsuspected, mites mentioned in our earlier discussion of household creatures. Since, as we have seen, many mites weren’t noticed by science at all until the middle of the twentieth century, to identify a family of them in 1886 was a signal achievement, particularly for a banker whose scientific pursuits were limited to evenings and weekends. No less significant was his study of the variability of nervous systems in insects, which lent important support to Darwin and his idea of descent with modification just at a time when Darwin really needed it.

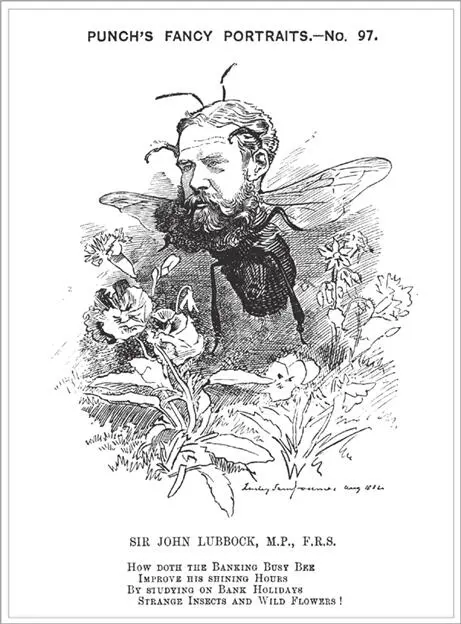

Punch cartoon of John Lubbock, architect of the Bank Holidays Act and the Ancient Monuments Protection Act (photo credit 19.1)

As well as being a banker and keen entomologist, Lubbock was also a distinguished archaeologist, a trustee of the British Museum, a member of Parliament, the vice chancellor (or head) of London University, and an author of popular books, among rather a lot else. As an archaeologist, he coined the terms palaeolithic, mesolithic , and neolithic , and was one of the first to use the handy new word prehistoric . As a politician and member of Parliament for the Liberal Party, he became a champion of the working man. He introduced legislation to limit the hours worked in shops to ten hours a day, and in 1871 he pushed through—virtually single-handedly—the Bank Holidays Act, which introduced the breathtakingly radical idea of a paid secular holiday for workers.* It is almost impossible now to imagine what excitement this caused. Before Lubbock’s new law, most employees were excused from work on Good Friday, Christmas Day or Boxing Day (but not generally both), and Sundays, and that was it. The idea of having a bonus day off—and in summer at that—was almost too thrilling to bear. Lubbock was widely agreed to be the most popular man in England, and bank holidays for a long time were affectionately known as “St. Lubbock’s days.” No one in his age would ever have supposed that his name would one day be forgotten.

But it is for one other innovation that Lubbock is of importance to us here: the preservation of ancient monuments. In 1872, Lubbock learned from a rector in rural Wiltshire that a big chunk of Avebury, an ancient circle of stones considerably larger than Stonehenge (though not so picturesquely composed), was about to be cleared away for new housing. Lubbock bought the threatened land, along with two other ancient monuments nearby, West Kennett Long Barrow and Silbury Hill (an enormous manmade mound—the largest in Europe), but clearly he couldn’t protect every worthy thing that grew threatened, so he began to press for legislation to safeguard historic treasures. Realizing this ambition was not nearly as straightforward as common sense would suggest it ought to be, because the ruling Tories under Benjamin Disraeli saw it as an egregious assault on property rights. The idea of giving a government functionary the right to come onto the land of a person of superior caste and start telling him how to manage his estate was preposterous—outrageous. Lubbock persevered, however, and in 1882, under the new Liberal government of William Ewart Gladstone, he managed to push through Parliament the Ancient Monuments Protection Act—a landmark piece of legislation if ever there was one.

Because the protection of monuments was such a sensitive issue, it was agreed that the first inspector of ancient monuments should be someone landowners could respect, ideally a large landowner himself. It so happened that Lubbock knew just the person—the man who was about to become his new father-in-law, none other than Augustus Pitt Rivers.

Their relationship through marriage must have been as surprising to them as it is to us. For one thing, the two men were nearly the same age. It just happened that the recently widowed Lubbock met Pitt Rivers’s daughter Alice on a weekend stay at Castle Howard in the early 1880s. Lubbock was nearly fifty, Alice just eighteen. What caused a spark between them is beyond plausible guessing, but they were married soon afterward. It wasn’t an outstandingly happy marriage. She was younger than some of his children, which made for awkward relationships, and appears to have had little interest in his work, but the one certainty is that life with Lubbock was better than being beaten to the ground with a riding crop.

Whether Lubbock was unaware of Pitt Rivers’s brutality to Alice or was simply prepared to overlook it—and little says more of the age than that either was possible—he and Pitt Rivers had a happy working relationship, no doubt because they had so many interests in common. As inspector of ancient monuments, Pitt Rivers’s powers were not spectacular. His brief was to identify important monuments that might be endangered, and to offer to take them into state care if the owner wished. Although this would relieve owners of the cost of maintaining sites, most balked because it was such an unprecedented step to cede control of any part of one’s estate. Even Lubbock hesitated before relinquishing Silbury Hill. The act carefully excluded houses, castles, and ecclesiastical structures. All that left were prehistoric monuments. The Office of Works provided Pitt Rivers with almost no money—half of his budget one year was spent on putting a low fence around a single burial mound—and in 1890 it removed his salary altogether, thereafter merely covering his expenses. Even then it asked him to stop “touting” for more monuments.

Pitt Rivers died in 1900. In eighteen years, he managed to list (or “schedule,” as the parlance has it) just forty-three monuments, barely over two a year. (The number of scheduled ancient monuments today is over nineteen thousand.) But he had helped set two immeasurably important precedents—that ancient things are precious enough to protect and that owners of ancient monuments have a duty to look after them. These policies weren’t always enforced with much rigor in his day, but the principles embedded in them were crucial, and they inspired others to take additional protective actions. The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, led by the designer William Morris, was founded in 1877, and the National Trust followed in 1895. At last British monuments began to enjoy some measure of formal protection.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «At Home»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «At Home» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «At Home» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.