Bill Bryson - At Home

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bill Bryson - At Home» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:At Home

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

At Home: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «At Home»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

At Home — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «At Home», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Lies in his bed, walks up and down with me ,

Puts on his pretty looks, repeats his words ,

Remembers me of all his gracious parts ,

Stuffs out his vacant garments with his form .

These are not the words of someone for whom children are a product, and there is no reason to suppose—no evidence anywhere, including that of common sense—that parents were ever, at any point in the past, commonly indifferent to the happiness and well-being of their children. One clue lies in the name of the room in which we are now.* Nursery is first recorded in English in 1330 and has been in continuous use ever since. A room exclusively dedicated to the needs and comforts of children would hardly seem consistent with the belief that children were of no consequence within the household. No less significant is the word childhood itself. It has existed in English for over a thousand years (the first recorded use is in the Lindisfarne Gospels circa AD 950), so whatever it may have meant emotionally to people, as a state of being, a condition of separate existence, it is indubitably ancient. To suggest that children were objects of indifference or barely existed as separate beings would appear to be a simplification at best.

That isn’t to say that childhood in the past was the long, carefree gambol we like to think it now. It was anything but. Life was full of perils from the moment of conception. For mother and child both, the most dangerous milestone was birth itself. When things went wrong, there was little any midwife or physician could do. Doctors, when called in at all, frequently resorted to treatments that only increased the distress and danger, draining the exhausted mother of blood (on the grounds that it would relax her—then seeing loss of consciousness as proof of success), padding her with blistering poultices or otherwise straining her dwindling reserves of energy and hope.

Not infrequently babies became stuck. In such an eventuality, labor could go on for three weeks or more, until baby or mother or both were spent beyond recovery. If a baby died within the womb, the procedures for getting it out are really too horrible to describe. Suffice it to say that they involved hooks and bringing the baby out in pieces. Such procedures brought not only unspeakable suffering to the mother but also much risk of damage to her uterus and even graver risk of infection. Considering the conditions, it is amazing to report that only between one and two mothers in a hundred died in childbirth. However, because most women bore children repeatedly (seven to nine times on average) the odds of death at some point in a woman’s childbearing experience rose dramatically, to about one in eight.

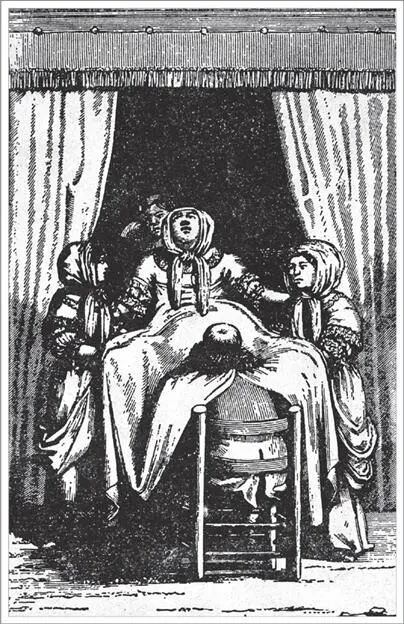

A woman giving birth in the eighteenth century (note the way modesty is preserved by the sheet pulled around the doctor’s neck ) (photo credit 18.1)

For children, birth was just the beginning. The first years of life weren’t so much a time of adventure as of misadventure, it seems. In addition to the endless waves of illness and epidemic that punctuated every existence, accidental death was far more common—breathtakingly so, in fact. Coroners’ rolls for London in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries include such abrupt childhood terminations as “drowned in a pit,” “bitten by sow,” “fell into pan of hot water,” “hit by cart-wheel,” “fell into tin of hot mash,” and “trampled in crowd.” The historian Emily Cockayne relates the sad case of a little boy who lay down in the road and covered himself with straw to amuse his friends. A passing cart squashed him.

Ariès and his adherents took such deaths as proof of parental carelessness and lack of interest in children’s well-being, but this is to impose modern standards on historic behavior. A more generous reading would bear in mind that every waking moment of a medieval mother’s life was full of distractions. She might have been nursing a sick or dying child, fighting off a fever herself, struggling to start a fire (or put one out), or doing any of a thousand other things. If children aren’t bitten by sows today, it is not because they are better supervised. It is because we don’t keep sows in the kitchen.

A good many modern conclusions are based on mortality rates from the past that are not actually all that certain. The first person to look carefully into the matter was, a little unexpectedly, the astronomer Edmond Halley, who is of course principally remembered now for the comet named for him. A tireless investigator into scientific phenomena of all kinds, Halley produced papers on everything from magnetism to the soporific effects of opium. In 1693, he came across figures for annual births and deaths in Breslau, Silesia (now Wroclaw, Poland), which fascinated him because they were so unusually complete. He realized that from them he could construct charts from which it was possible to work out the life expectancy of any person at any point in his existence. He could say that for someone aged twenty-five the chances of dying in the next year were 80 to 1 against, that someone who reached thirty could reasonably expect to live another twenty-seven years, that the chances of a man of forty living another seven years were 5 ½ to 1 in favor, and so on. These were the first actuarial tables, and, apart from anything else, they made the life insurance industry possible.

Halley’s findings were reported in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society , a scientific journal, and for that reason seem to have escaped the full attention of social historians, which is unfortunate because there is much of interest in them. Halley’s figures showed, for instance, that Breslau contained seven thousand women of child-bearing age yet only twelve hundred gave birth each year—“little more than a sixth part,” as he noted. Clearly the great majority of women at any time were taking careful steps to avoid pregnancy. So childbirth, in Breslau anyway, wasn’t some inescapable burden to which women had to submit, but a largely voluntary act.

Halley’s figures also showed that infant mortality was not quite as bad as the figures now generally cited would encourage us to suppose. In Breslau, slightly over a quarter of babies died in their first year, and 44 percent were dead by their seventh birthday. These are bad numbers, to be sure, but appreciably better than the comparable figures of one-third and one-half usually cited. Not until seventeen years had passed did the proportion of deaths among the young of Breslau reach 50 percent. That was actually worse than Halley had expected, and he used his report to make the point that people should not expect to live long lives, but rather should steel themselves for the possibility of dying before their time. “How unjustly we repine at the shortness of our Lives,” he wrote, “and think our selves wronged if we attain not Old Age; where it appears hereby, that the one half of those that are born are dead in Seventeen years.… [So] instead of murmuring at what we call an untimely Death, we ought with Patience and unconcern to submit to that Dissolution which is the necessary Condition of our perishable Materials.” Clearly expectations concerning death were much more complicated than a simple appraisal of the numbers might lead us to conclude.

A further complication of the figures—and a sound reason for women limiting their pregnancies—was that just at this time women across Europe were dying in droves from a mysterious new disease that doctors were powerless to defeat or understand. Called puerperal (from the Latin term for child ) fever, it was first recorded in Leipzig in 1652. For the next 250 years doctors would be helpless in the face of it. Puerperal fever was particularly dreaded because it came on suddenly, often several days after a successful hospital birth when the mother was completely well and nearly ready to go home. Within hours the victim would be severely fevered and delirious, and would remain in that state for about a week until she either recovered or expired. More often than not she expired. In the worst outbreaks, 90 percent of victims died. Until late in the nineteenth century most doctors attributed puerperal fever either to bad air or lax morals, when in fact it was their own grubby fingers transferring microbes from one tender uterus to another. As early as 1847, a doctor in Vienna, Ignaz Semmelweis, realized that if hospital staff washed their hands in mildly chlorinated water deaths of all types declined sharply, but hardly anyone paid any attention to him, and decades more would pass before antiseptic practices became general.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «At Home»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «At Home» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «At Home» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.