Bill Bryson - At Home

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bill Bryson - At Home» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:At Home

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

At Home: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «At Home»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

At Home — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «At Home», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Bazalgette brilliantly exceeded every expectation. In the process of building the new sewer system he transformed three and a half miles of riverfront through the creation of the Chelsea, Albert, and Victoria embankments (which is where a lot of that displaced earth went). These new embankments not only provided space for a mighty intercepting sewer—a kind of sewer superhighway—but also left ample room for a new Underground line and ducts for gas and other utilities below and a new relief road above. Altogether he reclaimed fifty-two acres of land, over which he scattered parks and promenades. An incidental feature of the embankments was that they narrowed the river and made it flow faster, improving its ability to cleanse itself. It would be hard to name an engineering project anywhere that offered a wider array of improvements—to public health, transportation, traffic management, recreation, river management—with a single scheme. This is the system that still drains London. Outside of the city’s parks, the embankments remain among the most agreeable environments in the city.

Because of the limits on his funds, Bazalgette could afford to take the sewage only as far as the eastern edge of the metropolis, to a place called Barking Reach. There mighty outfall pipes disgorged 150 million gallons of raw, lumpy, potently malodorous sewage into the Thames each day. Barking was still twenty miles from the open sea, as the dismayed and unfortunate people all along those twenty miles never stopped pointing out, but the tides were vigorous enough to haul most of the discharge safely (if not always odorlessly) out to sea, and ensured that there were never again any sewage-related epidemics in London.

The new sewage outfalls did, however, have an unfortunate role in the greatest tragedy ever experienced on the Thames. In September 1878, a pleasure boat named the Princess Alice , packed to overflowing with day-trippers, was returning to London after a day at the seaside, when it collided with another ship at Barking at the very place and moment when the two giant outfall pipes surged into action. The Princess Alice sank in less than five minutes. Nearly eight hundred people drowned in a choking sludge of raw sewage. Even those who could swim found it nearly impossible to make headway through the glutinous filth. For days afterward bodies bobbed to the surface. Many, the Times reported, were so bloated with gaseous bacteria that they wouldn’t fit into normal coffins.

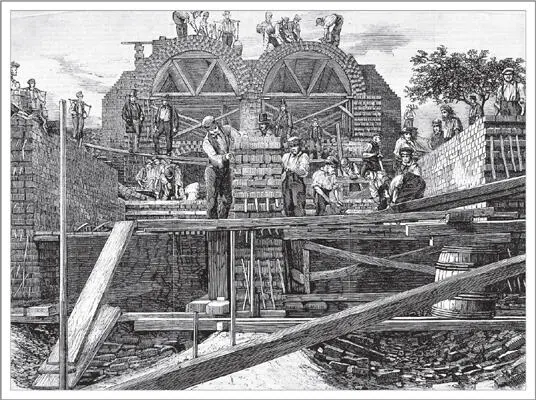

Construction of a sewage tunnel near Old Ford in Bow, East London (photo credit 16.1)

In 1876, Robert Koch, then an unknown country doctor in Germany, identified the microbe, Bacillus anthracis , responsible for anthrax. Seven years later, he identified Vibrio cholerae , another bacillus, as the cause of cholera. At long last there was proof that individual microorganisms caused specific diseases. It is remarkable to think that we have had electric lights and telephones for about as long as we have known that germs kill people. Edwin Chadwick never did believe that, and continued throughout his life to suggest ways of eliminating odors as the most effective method for keeping people healthy. One of his last and more singular proposals was to build across London a series of towers modeled on the new Eiffel Tower in Paris. In Chadwick’s vision, the towers would act as mighty ventilators, pulling in fresh, healthful air from the heights and pumping it back out at ground level. He went to his grave in the summer of 1890 implacably convinced that the cause of epidemics was atmospheric vapors.

Bazalgette, meanwhile, moved on to other projects. He built some of London’s handsomest bridges—at Hammersmith, Battersea, and Putney—and drove through the heart of London several bold new streets designed to alleviate congestion, including Charing Cross Road and Shaftesbury Avenue. Late in life he was knighted, but he never really received the fame he deserved. Sewer engineers seldom do. He is commemorated with a modest statue on the Victoria Embankment beside the Thames. He died a few months after Edwin Chadwick.

III

In America, the situation was more complicated than in England. Travelers to North America were often struck by the fact that epidemics tended to be rarer and milder there. There was a good reason for this: American communities were generally cleaner. This was not so much because Americans were more fastidious in their habits as because their communities were more open and spacious, creating less chance for contamination and cross-infection. At the same time, however, people in the New World had several additional diseases to contend with, and some of them were completely mystifying. One such was “the milk sick.” People who drank milk in America sometimes grew delirious and swiftly died—Abraham Lincoln’s mother was one such victim—but infected milk tasted and smelled no different from ordinary milk, and no one knew what the infectious agent was. Not until well into the nineteenth century did anyone finally deduce that it came from cows grazing on a plant called white snakeroot, which was harmless to the cows but made their milk toxic to drink.

Even more lethal and widely feared was yellow fever. A viral disease, it was called yellow fever because the skin of victims often turned sallow. The real symptoms, however, were high fever and black vomit. Yellow fever came into America aboard slave ships from Africa. The first case was in Barbados in 1647. It was a horrible disease. A doctor who got it said it felt “as if three or four hooks were fastened onto the globe of each eye and some person, standing behind me, was dragging them forcibly from their orbits back into the head.” Nobody knew what its cause was, but there was a general feeling—more instinct than intellectual certainty—that putrid water was at the root of things.

In the 1790s, a heroic English immigrant named Benjamin Latrobe began a long campaign to clean up water supplies. Latrobe was in America only because of a personal misfortune. He had been a successful architect and engineer in England when, in 1793, his wife died in childbirth. Devastated, he decided to emigrate to America, his mother’s native country, to try to rebuild his life. For a time he was the only formally trained architect and engineer in the country, and as such he landed many important commissions, from the Bank of Pennsylvania building in Philadelphia to the new Capitol Building in Washington.

His principal preoccupation, however, was with the belief that dirty water was killing thousands of people unnecessarily. After a devastating outbreak of yellow fever in Philadelphia, Latrobe persuaded the authorities to fill in the city swamps and bring in clean, fresh water from outside the city boundaries. The changes had a miraculous effect, and yellow fever never came back to Philadelphia with anything like the same force again. Latrobe took his efforts elsewhere and, ironically, while working in New Orleans in 1820, he contracted yellow fever himself and died.

Where cities failed to improve water supplies, heavy penalties were paid. Until about 1800, all Manhattan’s fresh water came from a single filthy pool—little more than a “common sewer,” in the words of one contemporary—in lower Manhattan known as the Collect Pond. But matters grew much worse as the population soared after the building of the Erie Canal. By the 1830s, it was estimated that a hundred tons of excrement were added to the city’s cesspits each day, often with contaminating effects on nearby wells. Water in New York was generally, and often visibly, polluted and undrinkable. New York in 1832 not only had a cholera epidemic, but also a yellow fever epidemic. Together they claimed more than four times as many victims as in Philadelphia with its cleaner water supplies. The dual outbreak acted as a spur to New York in much the way the Great Stink motivated London, and in 1837 work started on the Croton Aqueduct, which when finished in 1842 finally began to deliver clean, safe water to the city.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «At Home»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «At Home» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «At Home» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.