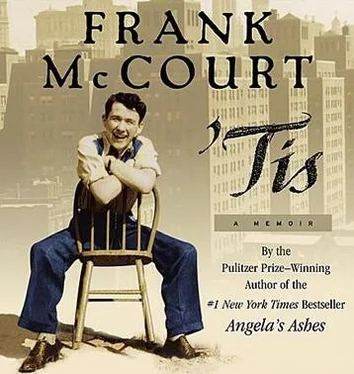

Frank McCourt - 'Tis

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Frank McCourt - 'Tis» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:'Tis

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

'Tis: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «'Tis»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

'Tis — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «'Tis», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

What I’m discovering now is that one thing leads to another. When Sean O’Casey writes about Lady Gregory or Yeats I have to look them up in the Encyclopedia Britannica and that keeps me busy till the librarian starts turning the light on and off. I don’t know how I could have reached the age of nineteen in Limerick ignorant of all that went on in Dublin before my time. I have to go to the Encyclopedia Britannica to learn how famous the Irish writers were, Yeats, Lady Gregory, AE and John Millington Synge who wrote plays where the people talk in a way I never heard in Limerick or anywhere else.

Here I am in a library in Queens discovering Irish literature, wondering why the schoolmaster never told us about these writers till I discover they were all Protestants, even Sean O’Casey whose father came from Limerick. No one in Limerick would want to give Protestants credit for being great Irish writers.

The second week of Introduction to Literature Mr. Herbert says that from his personal point of view one of the most desirable ingredients in a work of literature is gusto and that is certainly found in the works of Jonathan Swift and his admirer, our friend Mr. McCourt. If there is a certain innocence in Mr. McCourt’s apprehension of Swift it is leavened with enthusiasm. Mr. Herbert tells the class I was the only one of thirty-three people who selected a truly great writer, that it discourages him to think there are people in this class who consider Lloyd Douglas or Henry Morton Robinson great writers. Now he wants to know how and when I first read Swift and I have to tell him how a blind man in Limerick paid me to read Swift to him when I was twelve.

I don’t want to talk in class like this because of the shame last week but I have to do what I’m told or I might be kicked out of the university. The other students are looking at me and whispering to each other and I don’t know whether they’re sneering at me or admiring me. When the class ends I take the stairs again instead of the elevator but I can’t get out the door at the bottom because of the sign that says Fire Exit and warns me if I push anything there will be alarms. I climb back to the sixth floor to take the elevator but that door and the doors on the other floors are locked and there’s nothing to do but push the door on the ground floor till the alarm goes off and I’m taken to an office to fill out a form and write a statement as to what I was doing in that place causing alarms to go off.

There’s no use making a statement about my troubles with the teacher who mocked me the first week and praised me the second week, so I write that even though I dread elevators I’ll take them from this day out. I know this is what they want to hear and I learned from the army it’s easier to tell people in offices what they want to hear because if you don’t there’s always someone higher up who wants you to fill out a longer form.

25

Tom says he’s tired of New York, he’s going to Detroit where he knows people and he can make good money working on assembly lines in car factories. He tells me I should come with him, forget college, I won’t get a degree for years and even if I do I won’t make much money. If you’re fast on the assembly line you’re promoted to foreman and supervisor and before you know it you’re in an office telling people what to do, sitting there in your suit and tie with your secretary in a chair opposite tossing her hair, crossing her legs and asking if there’s anything you’d like, anything.

Of course I’d like to go with Tom. I’d like to have money to drive around Detroit in a new car with a blonde beside me, a Protestant with no sense of sin. I could go back to Limerick in bright American clothes except that they’d want to know what kind of work I was doing in America and I could never tell them I stood all day sticking bits and pieces into Buicks rolling past on the assembly line. I’d prefer to tell them I’m a student at New York University even though some would say, University? How in God’s name did you ever get into a university, you that left school at fourteen and never set foot inside secondary school? They might say in Limerick I always had the makings of a swelled head, that I was too big for my boots, that I had a great notion of myself, that God put some of us here to hew wood and draw water and who do I think I am anyway after my years in the lanes of Limerick?

Horace, the black man I nearly died with in the fumigation chamber, tells me if I leave the university I’m a fool. He works to keep his son in college in Canada and that’s the only way in America, mon. His wife cleans offices on Broad Street and she’s happy because they’ve got a good boy up there in Canada and they’re saving a few dollars for his graduation day in two years. Their son, Timothy, wants to be a child doctor so that he can go back to Jamaica to heal the sick children.

Horace tells me I should thank God I’m white, a young white man with the GI Bill and good health. Maybe a little trouble there with the eyes but still, better in this country to be white with bad eyes than black with good eyes. If his son ever told him he wanted to quit school to stand on an assembly line sticking cigarette lighters into cars he’d go up to Canada and break his head.

There are men in the warehouse who laugh at me and want to know why the hell I sit there with Horace during lunch hour. What is there to talk about with a guy whose grandparents just fell out of a tree? If I sit off at the end of the platform reading a book for my classes they ask if I’m some kind of a fairy and they let their hands go limp at the wrists. I’d like to sink my baling hook into their skulls but Eddie Lynch tells them cut it out, leave the kid alone, that they’re ignorant slobs whose grandparents were still in the mud and wouldn’t know a tree if it was rammed up their asses.

The men won’t answer Eddie but they get back at me when we’re unloading trucks by suddenly dropping boxes or crates so that my arms are jerked down and there’s pain. If one is operating the forklift he’ll try to pin me to the wall and laugh, Whoops, didn’t see you there. After lunch they might act friendly and ask how I enjoyed my sandwich and if I say fine they’ll say, Shit, man, didn’t you taste the pigeon shit Joey spread on your ham?

There are dark clouds in my head and I want to go after Joey with my baling hook but the ham rises in my throat and I’m throwing up off the platform with the men clutching each other and laughing, the only ones not laughing are Joey at the river end of the platform looking at the sky because everyone knows he’s not right in the head and Horace at the other end watching and saying nothing.

But after all the ham comes up and the retching stops I know what Horace is thinking. He’s thinking that if this were his son, Timothy, he’d tell him walk away from this and I know that’s what I have to do. I walk to Eddie Lynch and pass him my baling hook, making sure to offer him the handle to avoid the insult of the hook itself. He takes it and shakes hands with me. He says, Okay, kid, good luck, and we’ll send your paycheck. Eddie might be a platform boss with no education who worked his way up but he knows the situation, he knows what I’m thinking. I walk to Horace and shake hands with him. I can’t say anything because I have a strange feeling of love for him that makes it hard to talk and I wish he could be my father. He doesn’t say anything either because he knows there are times like this when words have no meaning. He pats my shoulder and nods and the last sound I hear at Port Warehouses is Eddie Lynch, Get back to work, you bunch of limp pricks.

On a Saturday morning Tom and I ride the train to the bus station in Manhattan. He’s on his way to Detroit and I’m taking my army duffel bag to a boarding house in Washington Heights. Tom gets his ticket, stows his bags in the luggage compartment, steps up on the bus and says, Are you sure? Are you sure you don’t want to come to Detroit? You could have a hell of a life.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «'Tis»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «'Tis» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «'Tis» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.