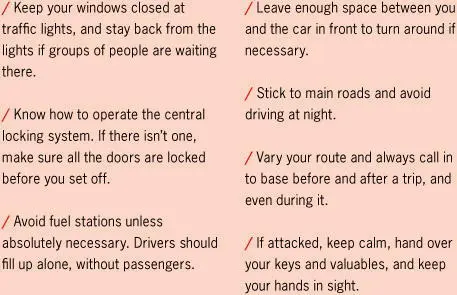

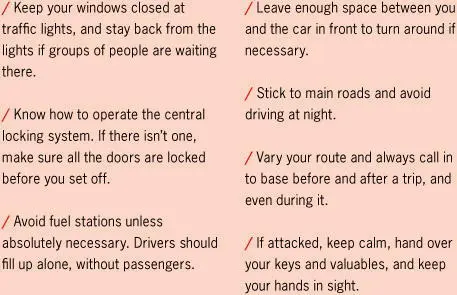

PRECAUTIONS AGAINST CAR-JACKING

‘During Israel’s war on Lebanon in 2006, Sky News and Fox News teamed up when moving by car. We always travelled in a five-car convoy with radio contact between the vehicles. We kept the vehicles spaced about half a kilometre apart in case of bombing from the air. It meant that in all likelihood we would lose only one car.

‘Driving from Beirut to the south we had one car filled with 250 litres of fuel, another filled with personal belongings, and a third with technical equipment. We let the fuel vehicle go in front – if a car was attacked, that would be the least valuable cargo – and the rest of us kept well back on the journey down.’

That said, a convoy can also be a target. On my way out of Baghdad for the last time I was looking for a cheap ride home. A group of gorgeous Italians offered me a seat in their car and told me to meet them at 4.30 a.m. outside our hotel the next day. (We always left before curfew as the streets were safest then.) I woke up at 4.25, my alarm having failed to go off for the first and only time in my life. As I huffed and puffed with my bag to the front door downstairs, the Italians were shutting their doors and about to head off. They shouted at me to jump into the car behind them and the whole convoy left on time. Instead of being surrounded by beautiful men, I found myself alone with a Canadian human shield, clicking on her knitting needles over murmured stitch counts.

We drove safely through the pitch-black, empty streets of Baghdad and onto the main road to Jordan. Dawn was breaking, and through the fudge of the grey morning I saw something that looked like a tank pull up onto the side of the road. It was still curfew and these were US forces, so our driver began to slow down. The Italians’ car, though, was still heading fast towards the tank when it was pumped full of bullets and came to a screeching halt. We slowed to a crawl and I leant out my window to wave to the soldiers as we approached the vehicle that was now more of a sieve than a taxi. The driver was dead – I could see that. The others, I have no idea, because the US soldiers shouted at us to move on as we were driving through the middle of an operation. We had broken curfew, as almost everyone did, in order to make it out of the city safely, and that car of happy men on their way home had borne the brunt of that calculated risk. It was a shocking day.

At times like that you realize nowhere is safe. Technology is never as advanced as it needs to be when it comes to identifying one person from another – the ‘enemy’ from the Red Cross or Red Crescent; the press van following an exit plan from a van full of fighters heading to the border; the refugees huddled around a fire from the locater flare for an artillery bombardment.

Historically, one-third of all deaths during war are from so-called ‘friendly fire’, and that statistic is getting no better. John Simpson, a BBC news correspondent, remembers one terrible occasion:

‘In 2003, during the invasion of Iraq, I thought it would be safe if my team and I tacked ourselves onto a convoy of American and Kurdish special forces. I remember saying to the others, “The Americans aren’t going to attack us if we’re with them.” But they did. A US Navy plane dropped a 1000-lb bomb right in the middle of our group. Eighteen people died, most of them burnt to death. My translator, who was standing close to me, had his legs blown off and died of blood loss. The rest of us were injured in different ways, none seriously. The fault was mine, and I still feel the guilt strongly.’

Apart from that occasion, John had always avoided travelling with the military for protection. It’s known as embedding and carries its own risks. You are travelling with the military and subject to their whims. You are, to all intents and purposes, enlisted in the army for those days and must forfeit your independence of movement and choice. The people the army are fighting regard you as just another soldier. Embedding can provide you access to a fight or an area you would never otherwise have seen, but it keeps you away from what is really going on. And John believes (rightly in my view) that it destroys the objectivity of your position as a journalist.

You’ll come across checkpoints along the road, at border crossings, or even in an airport. The road checks are the ones that pose the most danger, but being aware of your body language and using a skilled approach to people during any meeting will help ease your journey anywhere you travel.

Authority breeds arrogance, and that can be dangerous in a place where laws mean little. Before travelling through Yemen as tourists in 2005, my friends and I had a pile of travel passes printed off to give out to each checkpoint along the way. There were maybe 60 stops over four days of driving through the Hadramaut valley. At each one we were asked for a different level of search or bribe, even though our papers were in order. As frustration grew with the sticky heat of the day, it was difficult to approach each new checkpoint as a new conversation. When our car radiator fizzled out in the middle of a scrubby desert on day three, we looked ahead and saw a well-manned checkpoint about a kilometre away through the desert heat. They saw us and didn’t help. We wanted to scream and shout, but we eventually started the car again and chugged to their barrier, where they handed us water with big smiles and waved us through – no bribe, no search. It’s difficult to avoid judging one experience by your last, but you must.

When I met the senior news producer Shelley Thakral in Iraq she was a point of calm in all the madness, and the first visiting journalist in Basra who looked me in the eye and asked me if I was all right. It had been months since someone did that. She makes the following observations:

‘Your personality changes the more you work in these areas. You become more laidback. When it comes to checkpoints and crowds, calmness, patience and an understanding of the local culture are the way forward. Whatever you do, the guards will still insist on going through the whole frustrating procedure and you have to be very patient to put up with it. In Sri Lanka we were crossing back and forth into the Tamil Tiger region. We were tired and hot, struggling with heavy cases full of camera kit, but the guards don’t help to haul them up onto the table to be checked, even if you’re a woman. You feel resentful as they ask you to open them. But whatever you may think, it is necessary. You have to be calm and laidback.’

Assuming the guards are not actually hostile, there are some tried and tested ways to win them over. It starts with driving slowly and without your lights on full glare. Some countries may require you to have the lights on inside the car as you approach. Check the local guidelines.

Leith Mushtaq recommends: ‘Be friendly, but not too friendly. Give them some cigarettes, offer them something for tomorrow, but don’t give them everything. Make a deal. Ask them to be your escort today and offer them something for the next time. Go out of your way to find information about what is up ahead.’

Marc DuBois says: ‘The key is drinks. Often you find guys out in the middle of nowhere and a little cold water goes a long way. It opens a conversation. We also used to ask people if they had any mail to deliver to checkpoints further up the road. Nothing better than arriving at a checkpoint with mail from a little further back. If that doesn’t win over their trust, nothing will.’

As Dr Carl Hallam observes: ‘Checkpoints are interesting if they have a gun and you haven’t. You have to be very, very humble and avoid eye contact altogether. Don’t rush them, be patient. Take off your dark glasses and turn off your VHF radio, if you have one. If it blurts out at the wrong moment, it could frighten the person checking your papers. And always wait for the second car if there is more than one of you. Don’t drive off without the others.’

Читать дальше

![Джонатан Димблби - Barbarossa - How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/books/385421/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the-w-thumb.webp)