If a checkpoint isn’t a direct confrontation, it is always a negotiation. Marc DuBois has spent 12 years travelling round the world with MSF. Visiting Sudan in 2009, after 13 NGOs had been expelled by the government, was one of his more difficult recent projects. As he explains, all negotiations begin with one question – where should you target your efforts?

‘You have to know who is in charge. One of the biggest problems in negotiating is the failure to understand who is in charge in a given situation – whether it be a village, a checkpoint, a border or a government office. Often I see a person negotiating in vain with someone who doesn’t have the capacity to make a decision. With officials, it’s not always very clear. You can be in a meeting with someone whose political rank and title are correct, but in terms of real power it might be the national security person sitting in the corner that you need to win over. You need to understand that dynamic because it can be dangerous if you get it wrong.’

I like to have my documents handy – I don’t like rummaging around in pockets and glove compartments at checkpoints manned by jumpy individuals. You want to spend as little time there as possible; they’re notoriously dangerous places.

Chris Cobb-Smith

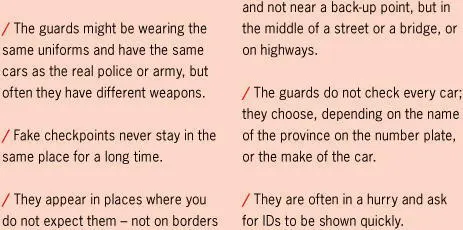

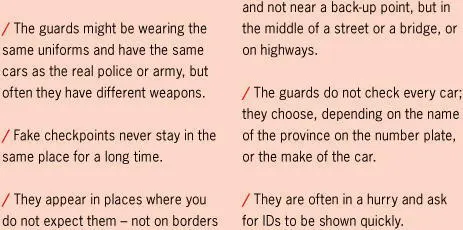

There are times when you need to be more than cautious, such as at fake checkpoints. Faking a checkpoint is an easy way to make a quick buck out of bribes, or robbery or kidnapping. Sometimes the fake checkpoint will have a particular target, so you might get through, but it is not worth trying your luck at getting through unless your pass has been previously negotiated by whoever is your local fixer on the ground with the right know-how and contacts.

Samantha Bolton recalls: ‘You are always told that you should turn on your lights and slow down. That’s the correct procedure. But I have also followed my instincts and run a checkpoint. In the Democratic Republic of Congo I was in the car with another girl. We were slowing down for a checkpoint, but even from a distance we could see they had bloodshot, bleary eyes and were moving around like they were drunk. We were out late after curfew and I didn’t feel right about it, so when they lowered their guns and surrounded our car, we suddenly sped up and went through the tin cans that were supposed to be the barrier. They tried to shoot at us, but I knew they were so drunk that it would be hard to hit us.’

Imad Shihab is an Iraqi journalist I worked with in Baghdad and Doha. In 2007 we evacuated together to the Green Zone when our entire office of local cameramen and producers were kidnapped. Some time later we found out that our largely Sunni staff were actually arrested by the mainly Shia police forces, but the Interior Ministry, which was in charge of the police, was not the best communicator at the time.

HOW TO SPOT A FAKE CHECKPOINT

HOW TO DEAL WITH A FAKE CHECKPOINT

Imad fled Iraq in 2009, when he became a target for trying to bring fair and balanced reports to the world. But he spent the worst years of the fight there, talking his way around the country street by street. He managed to stay safe, and from his hiding place he told me how to approach the most deadly of checkpoints. The advice can be applied to any country, not just to Iraq.

Imad Shihab knows the perils very well. He says: ‘I think that many of the victims of fake checkpoints and random arrests did not do their homework well enough. I did some strange things that people thought were funny, but they saved my life. Like having a Shia friend pretending to be a member of a fake checkpoint and asking me questions. These exercises were very helpful for me as a Sunni. A lot of victims would not have been killed if they had done the same.’

Of course there are other, more unorthodox, ways to get around checkpoints, as Nick Toksvig recalls: ‘After a bomb explosion in India an enterprising cameraman hired a fire engine to take him to the scene that had been cordoned off.’

Aid workers don’t have body armour. The logo on our T-shirt is our protection, but can become a target too.

Samantha Bolton

Take advice locally on what type of identification to put on your car. I have been in the middle of many riots where press and tourists were supposed to be able to travel freely, but that isn’t always the sentiment on the ground. Even the authorities may not be on message. Don’t expect legal protection where the law is under pressure from a popular movement or challenged by a resistance movement.

Nick Toksvig told me: ‘Spelling out “TV” or “Press” in gaffer tape on your vehicle used to work, but now many refugees fleeing battle zones do the same, as do local militias. Think about where you are before you attempt this type of vehicle identification. It can be meaningless.’

The road from Baghdad to Basra was notoriously dangerous after the US-led invasion of Iraq. There were frequent shootings, car-jackings and kidnappings. Fake checkpoints were set up along the route, and there was no way to get around them. If someone saw you in a car, they would call ahead for their friends to stop your car and target you. The road took six hours to drive very, very fast. The trip cost $6. I was being paid $10 day, so I thought I would try the train at just 50 cents.

The railway station in Baghdad was heaving with people – families getting ready for the long ride. The train left almost on time and off we went. We were told it would take six hours – in fact it took 16. There were no windows, and the train frequently stopped for hours at a time in the middle of nowhere or, even worse, in the middle of towns where people could look in and see my blonde hair. It was scary, but it felt like I was travelling under the radar. My friend Sebastian and I became mini-celebrities on the train, not exactly what we were aiming for. The journey ground on, and we ran out of water in the 50°C heat, so we were grateful for the hot, sandy wind rushing past our faces like the ultimate exfoliator. We had time to make friends with a family who went on to have me to stay with them for the next two months.

All along the way people slipped coffins onto the train, sitting on them to eat their sandwiches. And at the city of Najaf they jumped off, wailing with grief as they took their family member to the holiest Shia burial site.

Goats were lifted onto the train by boy herders, who stepped off with them an hour later, apparently aiming for a distant flapping tent in the desert.

We passed through the soggy marshlands and, at last, chugged slowly into Basra – safe and with enough change from our ticket to buy dinner for a week.

The problem with trains and buses is that the situation is beyond your control. If there are criminals on board, you will be their target. On the other hand, they won’t be expecting you to use the train or bus, so maybe they won’t be looking. However, take the following precautions:

• Lock your compartment if you can. I have used a luggage strap to fasten it in the past.

• Sleep in shifts if you are with others. Stay awake if you are alone.

• If you have to sleep, tie yourself to your valuables and sleep on top of your luggage.

• Try to travel during the day rather than at night.

James Brandon remembers a difficult journey: ‘Once I had to travel from Baghdad to Iraqi Kurdistan during a time of particularly bad unrest in Iraq. The 100-odd miles of road passed through several Sunni districts that were heavily infested with Al Qaeda and Baathist fighters. Despite this, I decided that the safest way to travel was by public bus. After all, I reasoned, a taxi or a private car was no safer, and might even be less so. No self-respecting bandits would bother with robbing a bus – they would assume that the passengers were too poor to make it worthwhile. Sunni fighters or Al Qaeda operatives looking for new hostages, meanwhile, would never expect a Westerner to travel through Iraq by bus. There was one problem, however: how could I carry my clothes, camera and notebook without attracting attention? Eventually I hit on the solution. I packed my stuff into cheap plastic grocery bags and headed to the bus depot. Once I got there, nobody looked at me twice. To the casual onlooker, I was just another down-on-his-luck Iraqi guy, his worldly possessions crammed into a couple of grimy plastic bags, saving a few precious dinar by taking the bus. As a result, the journey up to Kurdistan was entirely uneventful – and cheap! When it comes to blending in, you can never blend in too much.’

Читать дальше

![Джонатан Димблби - Barbarossa - How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/books/385421/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the-w-thumb.webp)