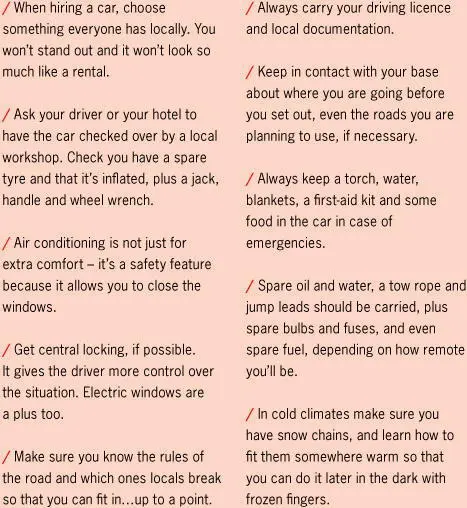

It’s very important to choose the right car – one that fits into the local area. Tom Coghlan tells you how to do that in Afghanistan:

‘Don’t use SUVs unless absolutely necessary. Toyota Corollas in Afghanistan are almost as durable as SUVs, a fraction of their cost to run and maintain, and the parts are available everywhere. They also attract a fraction of the attention. If you go somewhere dangerous, make sure you are the driver (if you are male). Nobody ever looks at the driver in Afghanistan because he has the lowest status in the car. Make sure the car is dirty. Girls should all wear burkas . Put all your identity documents in the back of the cover of the front seat. Play Afghan music on the stereo. Get a grubby look going and don’t wash your hair. To be honest, if people look in the car, they will probably identify you as foreign, but Afghans are quite polite and won’t harass you.

‘ In extremis the best thing to do is pretend to be physically disabled or mentally disturbed. It probably won’t help much, but there are lots of mentally disturbed people in Afghanistan, so you stand a chance of getting away with it. Because of the high instance of very close intermarriage, deaf and dumb people are quite frequent, and that’s an obvious option for the non-Pashto speaker.’

If you must drive yourself, learn how to drive in the local way. Nick Toksvig remembers: ‘We did a lot of our own driving during the 2006 war. What worked best was adapting to the way locals drove, whether through the use of lights or hand gestures or whatever. Adapt and you won’t stand out so much.’

According to journalist Sebastian Junger, though, your driving should be local in all but one way: ‘Wear a seatbelt! Every reporter I’ve ever met is cavalier about wearing a belt in a war zone, which is crazy.’

If you are driving in a war zone, you need to have a plan, make it known to everyone who needs to know, and stick to it. As one MSF volunteer told me, even small deviations from it can get you killed:

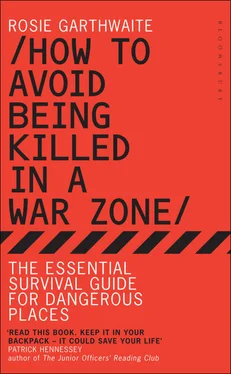

CHOOSING YOUR CAR

‘In Yemen we had strict laws on movement. It would take 4–8 hours to get from one town to another. To avoid tribal checkpoints, we would leave at four in the morning. On one occasion we decided to stop for a cup of coffee – a stupid, simple cup of coffee – so our driver pulled over at the nearest café. We then found we were in one of the most dangerous places we could be…it was a tribal zone with the highest risk ever. About 40–50 armed men surrounded us and they looked at us like we had dropped from heaven. As they were getting their weapons ready, one approached us to say we could leave if they could keep the car. We explained it was an ambulance, but they said they didn’t care – that we were working with another tribe and weren’t curing their people and they wanted it. The local driver told us to go back to the car and he would negotiate. He told them he would race them in the car and if they managed to catch us, they could keep the car. Thankfully, ours was better than theirs and we got away.’

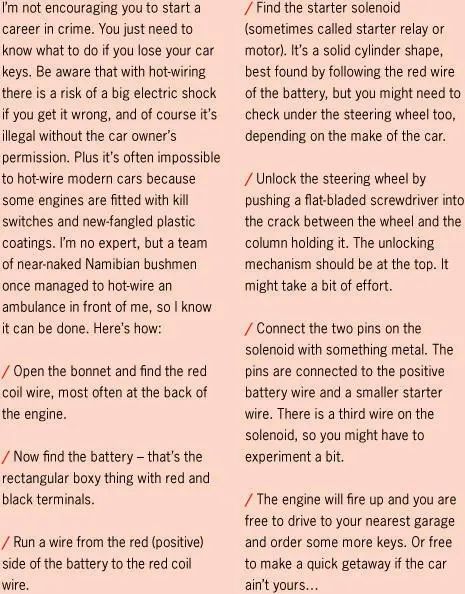

HOW TO HOT-WIRE A CAR

The threat of criminal attack obviously applies to places such as South Africa, where there is a high level of crime directed at homes and cars. But it also applies to places such as Mexico City, and Colombo in Sri Lanka, where kidnappers may be staking out your house. The information given here is not just for war zones.

The most fundamental piece of advice is never take the same route to work two days in a row. Never let your pattern become predictable. Leave at different times of the day if you can. One day have breakfast at work, the next have it at home. Have dinner out and return home late, but not every night. Look for any unusual cars outside your accommodation. Note down number plates so you can see if someone is returning again and again out of the blue. And if your instincts tell you to be scared, go to a hotel, or stay with a friend for a few nights.

Mary O’Shea had some interesting experiences as a new driver: ‘I moved to South Africa having driven for all of two weeks of my life. I landed in Johannesburg, bought a beat-up Ford Fiesta Flite (a tin can on wheels, specially manufactured for the African market) and had it kitted out with shatterproof windows, a tracking system and so forth, which ended up costing more than the actual car itself. Having diplomatic plates and being instructed never to stop at traffic lights is perhaps not the ideal starting point as a first-time driver. We were always reminded that most “incidents” take place as you get home, so the idea was to speed into the garage and get the gate shut behind you asap. Perhaps it’s not surprising that I managed to ram into my garage wall twice. Always keep an eye on cars around you to check if you are being followed. And if you see people lurking outside your house, drive past.’

The threat of being car-jacked is not confined just to those times of going into and out of your driveway, or to and from work. It could happen along the road too.

Qatar, where my Al Jazeera colleagues and I now live, is the kind of place where you can leave your keys in the car for days on end and no one will even think of stealing it. But back at her home in South Africa, senior news presenter Jane Dutton lives in a different world, where a simple trip to the shops can mean risking an attack from violent criminals. She explains the everyday precautions her colleagues, friends and neighbours take in order to minimize the risk:

‘I live next to the beautiful Vall River outside Johannesburg. The road heading there is one of the worst in the area for hijackings. The police have cut all the trees right back. And my family all drive very defensively, hyper-aware of the rear-view mirror – looking for cars that might be following, driving too close, or just behaving in a threatening way. Attackers used to put bricks out on the road to slow you down, so you have to watch for that too.

PRECAUTIONS AGAINST CAR BOMBS

‘Everyone knows not to stop at traffic lights, and never to pick up hitch-hikers. You must put your bag on the floor of the car and lock the doors and windows before you leave. In some areas further north from where I live, near Pretoria, they actually have signs warning passing drivers of a “Hijack Corner” coming up ahead.

‘Once I had a flat tyre while driving past the edge of a township with a particularly bad reputation. There I was in my high heels, vulnerable as anything. It was the fastest wheel change in history. You hear alarming stories all the time. Just last week my brother was driving home and a car rounded off on him to slow him down. He followed his instincts and sped onto the wrong side of the road until he came to a police car parked nearby. The policeman kicked a girl out of his car, popped his siren on and gave chase. That’s what it’s like in South Africa – more often than not you have to rely on yourself rather than the law.’

If the roads are dangerous, it’s a good idea to move in carefully organized convoys. Nick Toksvig has worked with teams carrying valuable camera equipment and potential hostages around all sorts of hostile environments. He explains how it’s done:

Читать дальше

![Джонатан Димблби - Barbarossa - How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/books/385421/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the-w-thumb.webp)