‘Taking a deep breath, I got out of the taxi and walked up to the US roadblock. In full view of the backed-up traffic jam, I had a loud argument with the troops on the inequities of their traffic policy, ignoring the soldiers’ guns that occasionally wavered towards my chest. The soldiers were, of course, unmoved by my arguments, but as I walked back towards the traffic jam, Iraqis gave me the thumbs up, patted me on the shoulder and offered me cigarettes. The moment of crisis had passed.’

But remain wary of fake friends. People will lie to you in order to get close to your fat wallet of dollars. They’ll tell you the stories you want to hear, rather than the truth, in order to win you over. They’ll lie about fellow workers in order to see them fired. They will lie about their qualifications and background in order to get a job they think might get them out of the country. And, worst of all, they might get paid to be your friend, in order to spy on you or lead you down a path to danger. Hoda Abdel-Hamid, an Al Jazeera English correspondent, told me about her dodgy experience:

‘I went to Iraq thinking, “I speak Arabic. I look like an Arab. No one will get me,” but I was just as vulnerable. We almost got kidnapped and killed on an empty university campus. Some guys circled us as we were interviewing someone. A professor called out of a window to warn us. She told us they were mujahideen [guerrilla fighters]. So we had been talking politely to our potential kidnappers. They were well dressed, well spoken and they had no weapons. We were going to follow them. Then all hell broke loose.’

Afghan jokes are impenetrable, so don’t try to make them. However, if you want to get in with a bunch of Afghans and they ask you any sort of question you don’t know the answer to, shrug and reply: ‘Because the sky is blue and the sea is green.’ When it is translated to them they will all fall about laughing and think you are quite the wit.

Tom Coghlan

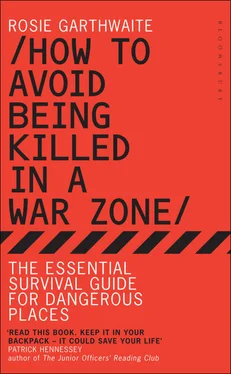

3/ Getting Around in a Dangerous Place

Be careful what you carry in a war zone. Take no detailed maps, no compass and no binoculars.

Sebastian Junger , journalist and author

‘Let’s make it a journey,’I said to my friend as we looked at the map of Mali and decided how we were going to get to Timbuktu for a music festival in the Sahara. There was a flight that would have plopped us a two-hour jeep ride away across the dunes. But instead it was adventure we sought, and boy did we pay for it.

A price agreed over the Internet was dismissed by our guide Aly Guindo when he picked me up from the airport. He had ‘forgotten to include the petrol’ and that was going to cost us $800 extra. Haggling was worthless; his gang had a monopoly on four-wheel drives, so we had little choice but to pay and go.

It was a beautiful morning as we rode through town, watching people set up their markets, crossing rivers busy with fishermen, passing mosques and churches sitting on top of each other. Aly talked of a four-hour drive to a world-famous mud mosque followed by four hours till dinner and sleep. Fourteen hot, sticky hours later he showed us our bed – a rooftop without a mattress or anywhere to hang a mosquito net. Or, we were told, ‘You can pay more money for a room.’ More money it was. And raucous laughter when we assumed the food was included (as they had told us when we made the deal).

The next day it was 16 hours at 100 kph across a ridged desert road. We turned orange in the dust that flowed in waves through the door. It was like being tied to a mechanical digger with five other people, relieved intermittently by river crossings in the scorching sun.

The final push was to Timbuktu. And our guide knew it was his last chance to get a tip. He told us he hadn’t been paid and that we needed to give him money so he could feed his family… and what seemed to us all to be a very heavy drug habit. We refused. Now everyone felt ripped off.

Eventually we made it, paying again at the door for our pre-paid tickets, and walked into what felt like a refugee camp. Tuareg families huddled around fires. Fat tourists, wearing blue Tuareg scarves to cover their burnt foreheads, stumbled around in the sand. We joined them, looking for our part of the camp. I had the name scribbled on a piece of paper, but had no idea where it might be, or who I could call to find out. But we did find it and thought the organizers were lovely until they charged us double too.

On the last morning, when our red-eyed driver turned up to take our bags to the car, we told him that he could give our seats to one of the six extra people we found sitting on the roof of his jeep. We had managed to get ourselves two precious tickets for a flight to Bamako, the capital of Mali. After three bone-rattling days on the road, followed by four in boiling-hot Sahara sunshine during the daytime and freezing temperatures at night, plus a good dose of food poisoning, we felt we deserved them.

I broke every rule I know about travelling during that holiday, all for the romance of the journey. It started with not following my instincts when Aly Guindo began to barter with me from the moment I left the airport.

Your first and last tool should be your instinct. When you are on the move in a dangerous world you have to make snap judgements. Trust your instincts. If you feel something isn’t right although it looks like the perfect day for it, whatever it is, stop and turn back.

Sherine Tadros told me a story that she attributes to diet-spurred guilt, but is probably as much to do with instinct: ‘Dr Atkins [of diet fame] saved my life. On the first night of the war in Gaza – 27 December 2008 – we were filming live shots from the main hospital in Gaza City. When we were done I was starving; we hadn’t stopped for 12 hours, since the first bombs started falling. There’s a great falafel stand next to the hospital, so I asked the team if we could stop and get a sandwich. When we got there I had an attack of food guilt: it was 11 p.m. – I shouldn’t be eating fried food and carbs. So we left it and went back to the office. A few minutes later we heard a huge explosion. The falafel stand and everyone in its proximity was blown up. Had we got the sandwiches, we would almost certainly have been killed. They say you should always trust your gut. Suffice to say that every decision you make in a war zone is vital and has consequences. Go with your instincts but realize that when it’s your time to go it’s your time to go.’

You should have a communications system in place from the moment you arrive. And even if all is quiet, it needs to be enforced from day one. Regular calls into base and from base should be established, even if it is just to say hello three times a day. This is especially key when you are travelling. Your point person should know where you are going, when you expect to arrive, the route you are travelling, and the plane, train or vehicle you are using to get there. You should arrange a time to call them when you arrive, and if you haven’t arrived by that time, you need to find a way to call in before they begin to panic. Communication is a priority.

Leith Mushtaq told me about the arrangements he made: ‘I made a deal with my base: “I will text you every hour. If I stop sending you texts, you must send help and try to find me.” And I keep drafts of two text messages, saying “We have been arrested” and “We have been kidnapped”. When we get stopped, before they take away the phone, I can send it.’

Being able to communicate is also vital if or when your vehicle breaks down. Make a note of a safe taxi number, along with your hotel address in the local language. Use your hotel’s taxi service when possible.

Читать дальше

![Джонатан Димблби - Barbarossa - How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/books/385421/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the-w-thumb.webp)