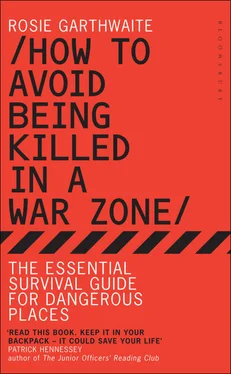

‘As for me, the strategy was to try to blend in. As ridiculous as that sounds, it was the advice I was given by an Iraqi colleague while mulling the offer of $200 a month plus expenses and a satellite phone. “If you want to survive as an ejnebi [foreigner] in Mosul for six months, start wearing clothes like mine,” he advised. So I went to Baghdad’s second-hand clothes market and purchased several nondescript nylon shirts, cheap trousers and some faux-leather shoes. As I checked into Mosul’s finest budget hotel, the manager peered over the counter and studied me carefully: “Kurdish?”

‘Over the next few months, as Iraq’s second city descended into violence, with death squads cruising the city in search of anyone collaborating with the occupation, the only occasions anyone gave me a second look was when I opened my mouth. Traipsing the streets with translator in tow, we looked like a pair of unsuccessful Iraqi businessmen. As we pushed our way through crowds thronging the scene of one of the many US military slayings I witnessed while down there, I took notes while he did the talking.

‘A low profile isn’t always going to be possible. But for a lone stringer living in a flat in Mosul and filing text reports for Reuters from Internet cafés over the winter of 2003, managing to avoid attention – at first glance at least – was the difference between being able to do my job, or ending up like Nicholas Berg, who was staying at my hotel before being kidnapped and then apparently beheaded live on the Internet. It was four months before I started being followed and had to leave town… I’ve still got those awful clothes in my wardrobe at home.’

If you want to blend in, it starts and ends with an integral understanding of the local body language, down to the smallest detail. As Tom Coghlan, defence correspondent for The Times , told me: ‘Southern Afghans don’t cross their arms, nor do they move their hands and bodies when they are talking. These they regard as a peculiar Western sort of acting. So if you are being Afghan, don’t do it either. Afghans also walk at half the pace of Europeans. Being shy and modest is quite normal, so looking at the ground is fine if you don’t want to be engaged.’

Doing what the locals do will often mean going against your instincts. James Brandon told me: ‘People in developing world war zones frequently look as if they have seen it all before. If you can mimic this quality, when necessary, it will increase your chances of staying alive. If you are walking down a street and see trouble brewing ahead, whatever you do don’t turn around, stare, run or slow down. Do what a local would do: keep your nerve and don’t panic. Trudge on past the incident, ignore everything and don’t catch anyone’s eye. You need to act as if you’ve seen everything before: after all, most locals probably have.

‘I once saw a Jordanian man kidnapped from his hotel in central Baghdad. As two men with guns fired warning shots over his head and forced him into a car, I stood at a tea stand no more than 10 yards away and calmly watched, sipping tea as this unknown man was forced into a car and driven away to his possible death. Keeping cool in such situations might save your life. By watching this incident with an Iraqi-style air of bored indifference, I escaped the attention of this particular kidnapping gang.

‘Unfortunately, after too many months of acting like this, the coldness stops being a mask: this aloofness from humanity becomes part of your character. I sometimes wonder what happened to that unknown man. Five years later I wonder if I should have intervened or somehow done something to help him.’

No matter what you look like or what presents you take, it is your body language that shows respect for the local culture. I have no fluent languages other than English, but all around the world there is a common language of humanity. You just have to learn the local dialect of body language and your message will be a lot clearer.

Zeina Khodr enlarges on this point: ‘They need to know that you are one of them. As a human, show them that you can relate to them. I went to meet a Taliban commander. At first I was shocked when 30 or 40 men emerged from nowhere with guns. But I remembered he had invited me as a guest. They wanted to talk to me, so I should assume the best. I told them I came from a place of conflict in Lebanon. We discussed something we had in common. That way it’s not like I am coming from Paris to talk to them about fighting in the jungle.

‘As a visitor to the area, I would be regarded as a guest by the local tribal elder in Afghanistan, and he would see me as his responsibility. Those feelings are even stronger if you are a female visitor. Having a woman in the team helps.

‘Little things help to show your respect. In Afghanistan don’t look men straight in the eye at checkpoints. They are not used to that from a woman.’

Fitting in is all about knowing how to approach people so that they forget the barriers that might otherwise exist outside that room. Monique Nagelkerke, MSF head of mission, told me: ‘When dealing with UN peacekeepers or with officials, and when trying to break the ice, look at the name on their shirt pocket and address the man with his name as printed on his uniform. Often it is long and difficult to pronounce, so you can always ask what his mother or wife calls him. This always worked for me until I met a sharp officer from India, who looked me straight in the eye and answered, “My mother always calls me Sweetheart.” Oh well, it did break the ice!’

Jon Snow is the chief presenter of Channel 4 News in the UK. He is as famous for his socks and ties as his challenging interviews. He was a long way from the studio in 1982 when he had a brush with a group of fighters north of the capital of El Salvador. ‘I had my life saved by a small gesture at the right time…by a man with a packet of Marlboro. A Dutch film crew had been killed and we wanted to find out what happened. We went to the area they had been murdered and found what seemed to be the same death squad. We looked into their eyes and thought we’d had it. My Italian fixer Marcelo Zinini got out a packet of cigarettes and handed them round. They put down their weapons and never picked them up again.’

And sometimes, says one former UN worker, who prefers to go unnamed, you need to know the body language in order to avoid offence. ‘Gestures for implying “Would you like a drink?” are not universal. The hand rounded, as if holding a glass, and tilting back into your mouth can imply something quite different in different cultures. This was a lesson I learnt when working as a cocktail waitress, with limited Spanish, in Buenos Aires many moons ago. The drink gesture in that part of the world is in fact a thumb gestured towards the mouth. I did well on tips however.’

Knowing the right gesture to make at the right time could save your life. Leith Mushtaq told me: ‘I am a white-skinned Arab. I was sitting having coffee in a teashop in Kandahar and there were some men who looked like Taliban. The tea boy told me they thought I was a kaffir [non-believer]. I got up and started saying a prayer, something I knew from childhood. It worked – they came and shook my hand.’

Countries of the Middle East, Asia and the Orient each have their own obsession with tea and coffee. It varies from country to country, and even from town to town.

In the Arab world the tea might come in a tiny cup, but after hours of brewing and often ladles of sugar, it will pack a punch. The coffee is delicious, cardamom-rich stuff in some areas, and just plain strong in others. It is not usually filtered, so don’t gulp down the muddy end of the cup. They will tap it out when you are offered more…and you will be offered more, and more and more until you can barely remember what it was like not to have every half hour and meeting punctuated with the ritual of pouring. It was when I totted up eight strong, sweet coffees in a day in Iraq that I knew it had to stop.

Читать дальше

![Джонатан Димблби - Barbarossa - How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/books/385421/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the-w-thumb.webp)