Paul Bremer, head of the Coalition Provisional Authority, controversially signed Coalition Provisional Authority Order 17, which stated that ‘Contractors shall not be subject to Iraqi laws or regulations in matters relating to the terms and conditions of their Contracts.’ It provided effective ‘immunity’ for contractors in the eyes of the Iraqis for them to do what they wanted.

In late 2008 a new law was approved by the Iraqi government, and Bush’s announcement of it was made more famous by a displeased Iraqi journalist throwing a shoe at him. It was agreed that ‘Iraq shall have the primary right to exercise jurisdiction over United States contractors and United States contractor employees’, so US contractors working for US forces would be subject to Iraqi criminal law. If US forces committed ‘major premeditated felonies’ while off duty and off base, they would be subject to the still undecided procedures laid out by a joint US–Iraq committee. However, the agreement is not totally clear and the immunity question is still being talked about.

Contractors are also subject to international laws, such as the Geneva Convention. This refers to ‘supply contractors’, which could include defence and private military contractors. Provided they have a valid identity card issued by the armed forces that they accompany, they are entitled to be treated as prisoners of war if captured. If they are found to be mercenaries, they are unlawful combatants and lose the right to prisoner of war status. This means that US contractors to the coalition forces in Iraq are subject to three levels of law – international, US and Iraqi.

Other commercial companies

There are many difficult aspects to operating a commercial company in a war zone. Among those that foreign nationals working for them should be aware of are the international anti-corruption measures, which will still be applicable to them. Perhaps the best known, thanks to rigorous enforcement and hefty fines, is the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), but there are also measures laid down by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and UN conventions. The UK Bribery Act (in effect since April 2010) is an interesting development as the UK has been relatively poor at investigating and prosecuting corruption offences in the past. This new law is wider in scope than the piecemeal ones it replaced, and it has extra-territorial reach.

Some of the red flags one should look out for as an employee working for commercial companies are requests for cash payments, requests for payments to third parties or offshore, requests for hospitality for government officials, or in fact any request if you are in a country with a reputation for corruption. The penalties can be quite substantial. Under the new British Act, for example, individuals guilty of one of the principal offences are liable on conviction to imprisonment for up to 10 years, or a fine, or both. If a deal ‘smells wrong’, it probably is, so it’s best to seek legal advice.

Journalists

In areas of conflict journalists are considered civilians under Additional Protocol I of the Geneva Conventions, provided they do not do anything or behave in any way that might compromise this status, such as directly helping a war, bearing arms or spying. Every journalist should ensure that they are not put in a compromising situation in relation to any of these things. A deliberate attack on a journalist that causes death or serious physical injury is a major breach of this Protocol and deemed a war crime.

Journalists should also note in what capacity they are travelling to a country in terms of Employment Law. Are they considered an employee or are they freelancing? Some media corporations have been criticized for preferring freelancers in order to save money or abdicate themselves of legal responsibility.

Medics

The First Geneva Convention of 1864 established that a distinctive emblem should be worn by medical personnel on the field of battle as an indication of their humanitarian mission and their neutral status. This is still the case today, and whether you’re wearing the Red Cross or the Red Crescent, make sure it’s visible to afford yourself this protection.

And a final thought from Tom… ‘Before travelling to any hostile environment, spare some thought for your legal position there and what laws apply. Remember, though, that the “rule of law” is often the very thing being fought for, so don’t expect it always to be upheld.’

James Brandon, a journalist who was kidnapped in Iraq in 2004, offers the following advice: ‘Deciding when to leave a war zone is as important as deciding when to arrive. Many people are killed or kidnapped because they stay too long. Typically, people arrive in war zones feeling wary, suspicious and paranoid. In many cases, however, they become more relaxed the longer they are there. Danger becomes so omnipresent that people sometimes become fatalistic (“Everybody dies one day” is a typical refrain you hear in war zones). For example, a person new to a war zone might estimate the chances of being killed while doing such-and-such activity and decide that if the odds of getting killed are more than 1–1000, they won’t do it. But after a few months they might say that a 1–50 chance of being killed on a particular mission is “do-able”. A few more months, however, and a 50:50 chance of being killed starts to look like playable odds. That’s when it’s time to leave.’

It might seem strange to plan your exit before you arrive, but for the sake of friends, family and your own sanity, it is a very good idea.

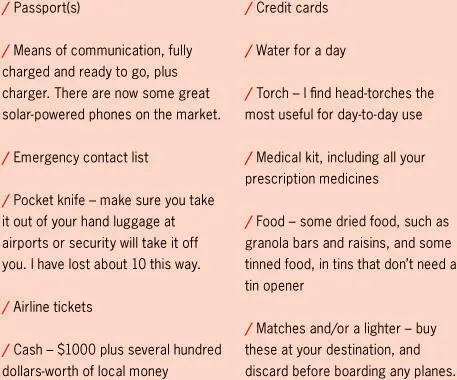

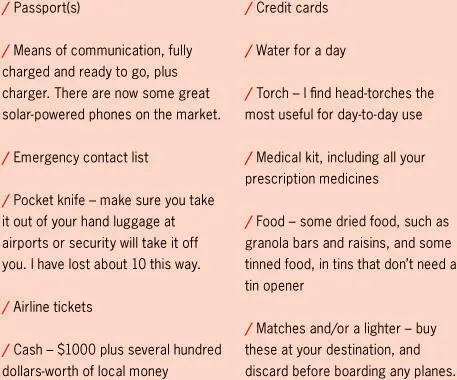

YOUR GRAB BAG MUST INCLUDE…

Also known as a ‘sac d’evac’ or ‘crash bag’, this is the bag you will grab when the bombs are raining down and you head to a bomb shelter. It is the only thing you will have with you if you are evacuated in a rush. It is the one bag you will put in a safe or a friend’s hotel room if you think someone uninvited might be coming into yours when you pop out for dinner later.

Nick Toksvig recalls how important this bag can be: ‘During the Russia–Georgia conflict, a car with four Sky News people was stopped by armed men. They were forced out and the car was stolen. Inside was their luggage and camera equipment. One guy had got out with his shoulder bag still around his shoulders. It contained money, passport and water. It got them out of there.’

A grab bag is not optional. Everybody needs one. It can be as small as a bum bag, but it had better be bloody good. The stuff you put in there can save your life. You should check it every evening before you go to bed. You should put chargers and passports straight back into their assigned pocket the moment you have used them. You might also decide to put a packet or two of cigarettes in there, or a book; you’ll have your own priorities.

I went into Baghdad with a backpack full of ugly baggy clothes, a book about Iraq by Dilip Hiro, a lot of tampons, a very good Berlitz Arabic phrasebook, a head-torch, a corkscrew/bottle opener (I never travel anywhere without a corkscrew) and a couple of hundred dollars. They all came in useful at one time or another. Having been in the army, I am pretty good at packing a lot into a small space.

I thought I was well prepared, but if I had thought for a bit longer, there was so much more I could have done to help my journey. It is better to carry more than less if you can. The most experienced people in war zones tend to come with a house-load of stuff and then dump it all in an emergency. Of course, the amount you take also depends on your mode of transport. The not-so-funny stories I have heard about people getting killed on the way to buy a razor, or getting pregnant because all the local condoms were out of date should be a lesson to all.

Читать дальше

![Джонатан Димблби - Barbarossa - How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/books/385421/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the-w-thumb.webp)