“Don’t worry, Jean dear,” says Annie, smiling at him. These words reassure him. They are still sitting in the same seats after lunch. No-one else in the restaurant car. The train stops at a large station. He asks her whether they have arrived. Not yet, Annie tells him. She explains to him that it must be six o’clock in the evening and that it is always this time when you arrive in this city. Some years later, he would frequently catch the same train and he would know the name of the city where one arrives at dusk in winter. Lyon. She has taken a pack of cards from her handbag and she wants to teach him how to play patience, but he does not understand it at all.

He has never made such a long journey. No-one has come to disturb them. “They’ve forgotten us,” Annie tells him. And the memories he still has of all this have also been worn away by forgetfulness, apart from a few more distinct images when the film slips and eventually gets stuck on one of them. Annie rummages in her bag and hands him the navy-blue folder — his passport — so that he remembers his new name carefully. In a few days’ time they will cross “the frontier” to go to another country and to a city that is called “Rome”. “Remember this name carefully: Rome. And I swear to you that they won’t be able to find us in Rome. I’ve got friends there.” He does not really understand what she is saying, but because she bursts out laughing, he starts to laugh as well. She plays patience again and he watches her laying the cards in rows on the table. The train stops once more at a large station, and he asks her whether they have arrived. No. She has given him the pack of cards, and he enjoys sorting them out according to their colours. Spades. Diamonds. Clubs. Hearts. She tells him that it is time to go and find the suitcases. They go back along the corridors of the coaches in the opposite direction, and she holds him sometimes by the neck, sometimes by the arm. The corridors and the compartments are empty. She says that all the passengers have got off before them. A ghost train. They find their suitcases in the same place at the entrance to the coach. It is dark and they are on the deserted platform of a very small station. They go down a lane that runs alongside the railway track. She stops in front of a door hollowed out of a surrounding wall and she takes a key from her handbag. They walk down a path in the dark. A large white house with lights on in the windows. They go into a room that is very brightly lit and has black and white tiling. In his memory, however, he confuses this house with the one in Saint-Leu-la-Forêt, probably because of the short time he spent there with Annie. The bedroom he slept in down there, for instance, seems to him to be identical to the one in Saint-Leu-la-Forêt.

Twenty years later, he happened to be on the Côte d’Azur and he had thought he recognised the little station and the lane they had walked down between the railway track and the walls of the houses. Èze-sur-Mer. He had even questioned a man with grey hair who ran a restaurant on the beach. “That must be the old Villa Embiricos on Cap Estel. .” He had jotted down the name just in case, but when the man added, “A Monsieur Vincent had bought it during the war. Afterwards it was impounded. Now, they’ve turned it into a hotel”, he felt afraid. No, he would not return to places for the sake of recognising them. He was too frightened that the grief, buried away until then, might unfurl through the years like a Bickford fuse.

They never go to the beach. In the afternoons, they stay in the garden, from where you can see the sea. She found a car in the garage of the house, a car that was bigger than the one at Saint-Leu-la-Forêt. In the evenings, she takes him to have dinner in the restaurant. They take the Corniche road. It is in this car, she tells him, that they will cross “the frontier” and drive as far as “Rome”. On the last day, she would often leave the garden to make telephone calls and she seemed anxious. They are sitting opposite one another beneath a veranda, and he is watching her playing patience. She leans over and she frowns. She appears to be thinking a great deal before laying down one card after another, but he notices a tear trickling down her cheek, so small that you can hardly see it, as on that day, at Saint-Leu-la-Forêt, when he was sitting in the car beside her. In the night, when she speaks on the telephone in the bedroom next door, he can hear only the sound of her voice and not the words. In the morning, he is woken up by the rays of the sun that peep into his bedroom through the curtains and make orange patches on the wall. To begin with, it is almost nothing, the crunch of tyres on the gravel, the sound of an engine growing fainter, and you need a little more time to realise that there is no-one left in the house apart from you.

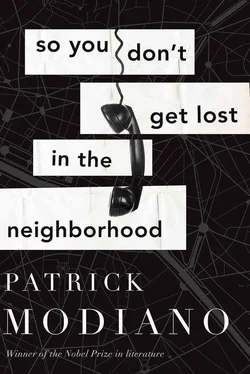

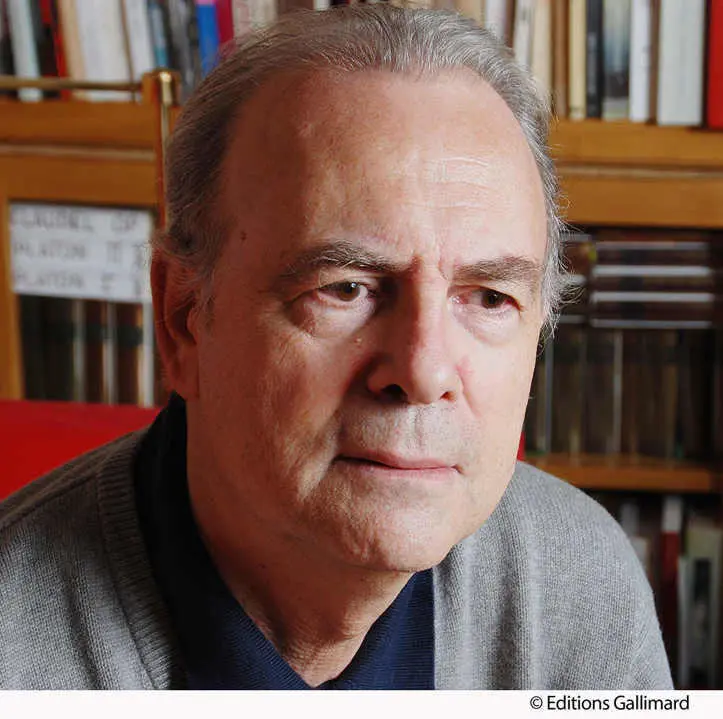

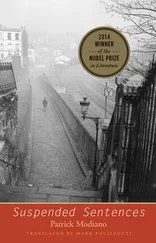

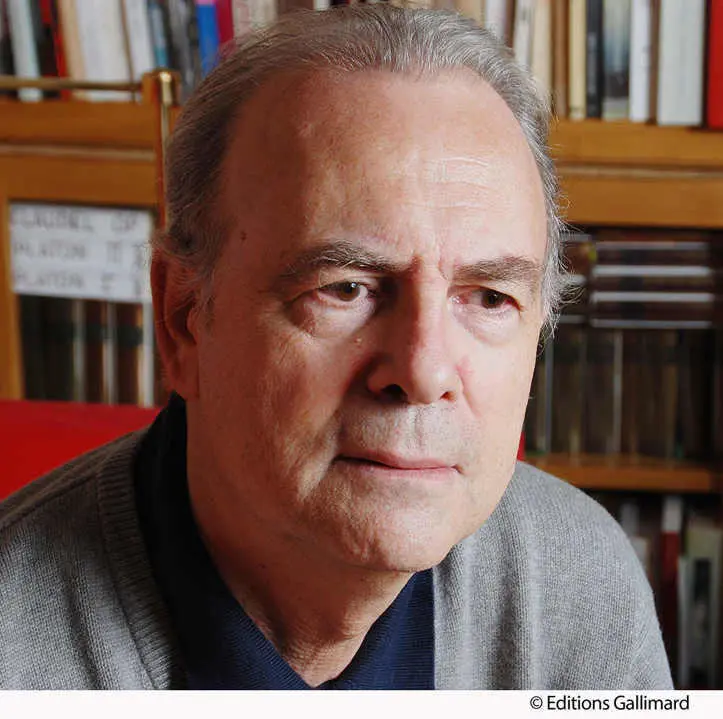

PATRICK MODIANO was born in Paris in 1945. His first novel, La Place de l’étoile , was published in 1968 when he was just twenty-two and his works have now been translated into over thirty languages around the world. He won the Austrian State Prize for European Literature in 2012, the 2010 Prix Mondial Cino Del Duca from the Institut de France for lifetime achievement, the 1978 Prix Goncourt for Rue de boutique obscures , and the 1972 Grand Prix du roman de l’Académie française for Les boulevards de ceinture . He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2014.

EUAN CAMERON’s translations include works by Julien Green, Simone de Beauvoir and Paul Morand, and biographies of Marcel Proust and Irène Némirovsky.