“Do you remember her?”

“Slightly. . She was very young when she left the neighbourhood. According to what Pierre had told me, she was protected by a woman who ran a nightclub in rue de Ponthieu. .”

Daragane wondered whether he was not confusing Annie with someone else. And yet a girlfriend of hers, Colette, often came to Saint-Leu-la-Forêt and, one day, they had driven her back to Paris by car, to a street near the Champs-Élysées gardens where the postage stamp market used to take place. Rue de Ponthieu? The two women had gone into a building together. And he had waited for Annie on the back seat of the car.

“You don’t know what became of her?”

The man looked at him somewhat suspiciously.

“No. Why? Was she really a friend of yours?”

“I knew her in my childhood.”

“Well, that changes everything. . It’s all in the past now. .”

He had begun to smile again and he leant over towards Daragane.

“A longtime ago, Pierre told me that she had had some problems and that she had been in prison.”

He had used the same words that Perrin de Lara had, the evening of the previous month when he had come across him sitting alone on the terrace of a café. “She had been in prison.” The tone of each of the two men was different: a slightly disdainful, distant manner, in the case of Perrin de Lara, as though Daragane had obliged him to talk about someone who was not from his world; a kind of familiarity in the case of the other, since he knew “her brother Pierre” and because “being in prison” appeared to be fairly commonplace to him. Was it on account of certain customers of his who came, he had explained to Daragane, “after eleven o’clock at night”?

He thought that Annie would have given him some explanations if she was still alive. Later on, when his book had been published and he had been fortunate enough to see her again, he had not asked her a single question about this matter. She would not have replied. Neither had he mentioned the room in rue Laferrière, nor the sheet of paper folded in four on which she had written their address. He had lost that sheet of paper. And even if he had been able to keep hold of it for fifteen years and had shown it to her, she would have said: “But, Jean dear, that’s not at all like my handwriting.”

The man at the Aero did not know why she had been in prison. “Her brother Pierre” had not given him any details about it. But Daragane remembered that the day before they left Saint-Leu-la-Forêt she seemed nervous. She had even forgotten to come to collect him from school at half-past four, and he had returned to the house on his own. That had not really bothered him. It was easy, all you had to do was continue straight along the road. Annie was on the phone in the drawing room. She had given him a wave and had gone on talking on the phone. In the evening, she had taken him to her bedroom, and he watched her filling a suitcase with clothing. He was frightened that she might leave him alone in the house. But she had told him that tomorrow they would both be going to Paris.

In the night, he had heard voices in Annie’s bedroom. He had recognised that of Roger Vincent. A little later on, the noise from the engine of the American car grew fainter and eventually subsided. He was frightened of hearing her car starting up. And then he fell asleep.

One late afternoon when he was leaving the Aero after having written two pages of his book — the building works in the former hotel stopped at about six o’clock in the evening — he wondered whether the walks he had been on fifteen years ago while Annie was away had taken him as far as this. There could not have been very many of these walks and they must have been shorter than he remembered. Had Annie really allowed a child to wander around alone in this neighbourhood? The address written in her handwriting on the sheet of paper folded in four — a detail that he could not have invented — was certainly proof of this.

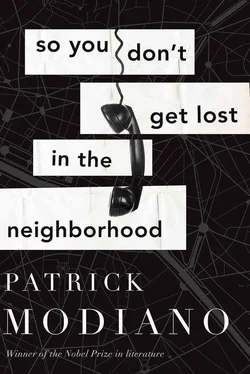

He recalled having walked along a road at the end of which he could see the Moulin-Rouge. He had not dared go further than the central reservation of the boulevard for fear of getting lost. As a matter of fact, it would only have required a few steps for him to find himself at the spot where he was now. And the thought of this gave him a strange sensation, as though time was irrelevant. It happened fifteen years ago, he was walking on his own, very near here, in the July sunshine, and now it was December. Every time he left the Aero, it was already dark. But suddenly, for him, the seasons and the years merged together. He decided to walk as far as rue Laferrière — the same route he used to take in the past — straight on, keep straight on. The streets were on a slope and, as he walked further down, he felt certain that he was going backwards in time. The darkness would grow brighter at the bottom of rue Fontaine, it would be daylight and there would be that July sunshine. Annie had not merely written the address on the sheet of paper folded in four, but the words: SO YOU DON’T GET LOST IN THE NEIGHBOURHOOD, in her large handwriting, an old-fashioned handwriting that was no longer taught at the school in Saint-Leu-la-Forêt.

The slope on rue Notre-Dame-de-Lorette was as steep as the previous street. You just had to let yourself glide along. A little further down. On the left. Only once had they gone back together to their room when it was dark. It was the day before they set off by train. She had her hand on his head or on his neck, a protective gesture to assure herself that he really was walking beside her. They were returning from the Hôtel Terrass beyond the bridge that overlooks the cemetery. They had gone into this hotel, and he had recognised Roger Vincent, in an armchair, at the back of the foyer. They sat down with him. Annie and Roger Vincent were talking to one another. They forgot he was there. He listened to them without understanding what they were saying. They were speaking too quietly. At one moment, Roger Vincent repeated the same thing: Annie must “take the train” and she must “leave her car in the garage”. She disagreed, but she had eventually said to him: “Yes, you’re right, it’s more sensible.” Roger Vincent had turned to him and had smiled. “Here, this is for you.” And he had handed him a navy-blue folder and told him to open it. “Your passport.” He had recognised himself on the photograph, one of those they had had taken in the Photomaton booth where, on each occasion, the extreme brightness of the light had made him blink. He could read his first name and his date of birth on the opening page, but the surname was not his, it was Annie’s: ASTRAND. Roger Vincent had told him in a solemn voice that he must use the same name as the “person accompanying him”, and this explanation had been enough for him.

On the way back, Annie and he walked along the central reservation of the boulevard. After the Moulin-Rouge, they had taken a small street, on the left, at the end of which stood the front of a garage. They had passed through a workshop that smelt of darkness and petrol. At the very back was a glass-panelled room. A young man was standing behind a desk, the same young man who sometimes came to Saint-Leu-la-Forêt and had taken him to the Cirque Médrano one afternoon. They spoke about Annie’s car, which could be seen, over there, parked alongside the wall.

He had left the garage with her, it was dark and he had wanted to read the words on the neon sign: “Grand Garage de la Place Blanche”, the same words that he read again, fifteen years later, leaning out of the window of his bedroom at 11 rue Coustou. When he had switched off the light and was trying to get to sleep, reflections in the shape of trellis work were projected onto the wall, opposite his bed. He went to bed early, because of the building works that started up again at about seven o’clock in the morning. It was difficult for him to write after a bad night. In his drowsiness, he could hear Annie’s voice, more and more distant, and all he could understand was the end of a sentence: “. . SO YOU DON’T GET LOST IN THE NEIGHBOURHOOD. .” On waking up, in this bedroom, he realised that it had taken him fifteen years to cross the street.

Читать дальше